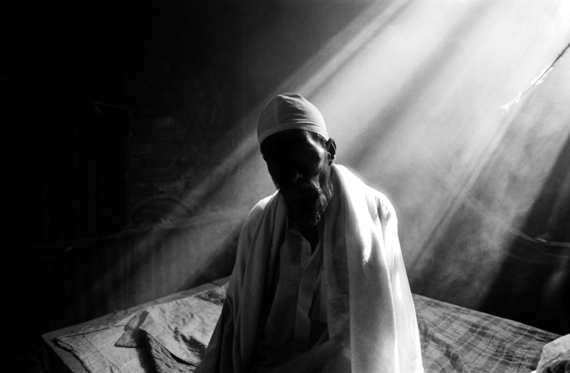

An ailing 75-year-old Urdu-speaking man sits alone in his room in Pat Godam Camp in Mymensingh, Bangladesh. He has no family left and does not have the resources to obtain health care. In Bangladesh, the Urdu-speaking Bihari community was stateless for more than 35 years. After Bangladesh's independence from Pakistan, hundreds of thousands of Bihari were moved into ghetto-like settlements in cities all over Bangladesh. In 2008, the Bihari were granted Bangladesh nationality but still face challenges in accessing passports, land ownership, employment in government and military and obtaining trade-licenses. (2006)

- Statelessness refers to the condition of an individual who is not considered a national by any state. Although stateless people may sometimes also be refugees, the two categories are distinct.

- It's almost impossible to determine the true number of stateless people. For 2014, UNHCR offices reported a figure of almost 3.5 million stateless people, drawing specifically on data from 77 countries. However, it is estimated that there are more than 10 million stateless worldwide.

In 2002, photojournalist Greg Constantine had been working on a story about North Korean defectors. Some of these were women who had lived in China, in hiding, having given birth there to children whom they would later take with them in escaping China via a kind of underground railroad.

The issue for these children: they were stateless.

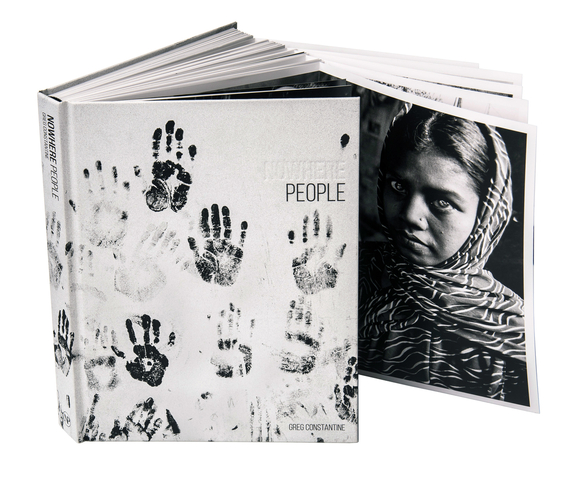

This would be the first time Constantine had come across this issue--one that would compel him to begin a several-year project that would culminate in the book, Nowhere People (2015), which depicts some of the most vulnerable among stateless communities internationally--and for whom basic human rights are often categorically withheld.

At the time he had met these North Korean women, as Constantine says, some basic questions came to the fore regarding their children, and they were questions that could easily be asked of any of the stateless communities he has subsequently documented.

[These] children had no documents. No birth certificates, no passports, etc. They possessed nothing that proved their legal identity. And that made me ask questions, 'how will the kids go to school?'. 'how will they be able to travel?' 'what happens if they need to go to the hospital?', etc. All the answers led to the children really having no future ahead of them. It took another 3 years before I would make the decision to embark on the project Nowhere People, with the intention of it only being a one-year project on stateless people in Asia. It didn't take long for me to realize I was working on an under-reported story of huge proportion. Each year the project got bigger and bigger. I became more and more dedicated to chronicling this global issue and the stories of stateless people, and each year, I could see how the issue of statelessness itself touched on some much bigger themes that I wanted to explore.

Also similar--the emotions among stateless communities, including their notions of "home."

Many of the stateless people and communities I've spent time photographing have a very deep sense of belonging to the place in which they live. Most stateless people are NOT refugees. Most stateless people around the world, from the Bidoon community in Kuwait to Rohingya in Burma, to Nubians in Kenya or ethnic Burkinabe in the Ivory Coast, to young Roma in Italy and Dominicans of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic, they have never left the country where they were born, where their parents were born and grandparents, etc. They know where they belong. They know where home is. I've tried to show this connection to place in so many of my photographs. But for any number of reasons mostly because of deep-rooted discrimination, racism, intolerance, political greed, the State has made the conscious decision to deny them this recognition and affirmation of their belonging to this place they call and consider home. And this thing, citizenship, which most of us associate with 'rights' and 'inclusion' has been used for the very opposite purpose....deprivation, rejection and exclusion. The arbitrary denial of citizenship by the State has been used as a weapon to exclude and marginalize. This has a huge psychological impact on stateless people all over the world. It places this heavy feeling of being 'incomplete' on stateless people.

Because states can use citizenship as a weapon against vulnerable communities, especially those whom they consider to be problematic, and against whom the state can facilitate racial, ethnic, or religious hatreds and discrimination via their own actions, being called upon the proverbial carpet for such actions can be a sensitive topic--and one that diplomatically can run the risk of causing rifts when addressed by outside actors--whether governments, INGO's, or others for whom human rights, including when codified by international law, may be an essential element of their interaction with a particular government.

Statelessness is an incredibly sensitive subject to talk about because in most cases, it is governments themselves that actually cause people to be stateless in the first place and it is governments that actually perpetuate statelessness for decades. You are touching on the right of a sovereign State to determine who its citizens are and aren't. Almost every country in the world is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and in that convention it clearly says that every child has a right to a nationality, yet you have countries all over the world that disregard their obligation. How is this enforced? How does the international community turn to a country like the Dominican Republic or Myanmar and hold them accountable for not living up to their obligations or for actions that are in clear disregard of international treaties?

Stateless people want their stories heard. They want their stories told. They want people to know about their struggles and that they don't accept the situation they are in. So much of the conversation about statelessness has focused on the legal elements embedded in the issue. Far too often, the human stories of how statelessness impacts people were either not there or were lost in the process.

In Myanmar, over 800,000 people from the Rohingya community have been arbitrarily denied citizenship and are stateless. Ethnic violence in 2012, forced tens of thousands of Rohingya from their homes and into camps for internally displaced people. Rohingya worry that an entire generation of children will not have access to schools and an education. Most children, like 7-year-old Nur, who hauls mud at a worksite near one of the camps, have never been to school. (2014)

In terms of the role of the media, including those like Constantine who are at the forefront of topics in which human rights can seem abstract, depicting statelessness is essential to evoke the kind of visceral or emotional response that can only be done in some cases through a visual medium. Here, Constantine has taken inspiration from such photojournalists as Philip Jones Griffiths, Eugene Richards, Ed Kashi, Sebastiao Salgado, Brenda Ann Keneally, Stephanie Sinclair, Robin Hammond, Kathryn Cook, Jon Lowenstein, and Kadir Van Lohuizen, among others--especially those for whom photography and social justice have become an important amalgam.

For years, I think people discussed the issue of statelessness but there was almost nothing there to show people what statelessness actually looked like. Ie: Show us what happens to people and communities when they are stateless. Photography is a language, and as people and policy makers have had discussions about the legal elements of statelessness, I've always felt the visual stories of stateless people need to be included as a language in that conversation as well.

In terms of Constantine's work, Nowhere People is a testament to the capacity to use that photographic language for necessary reasons. However, like any human rights issue, and with the media becoming less a public good and more and more a commercial interest, it still can be a hard sell, even when the issues themselves address an even larger, more pervasive truth about the role of government itself in the lives of those for whom they are ultimately responsible. That is a topic that has continued to be relevant to every human being, regardless of form of government when it comes to the authority of a state and those under which it can exert myriad levels of power or control.

I've always been surprised that this issue of statelessness and the story of stateless people hasn't received more attention. To say getting editors interested in this story has been an uphill battle is an understatement. People have said statelessness is a story that doesn't have much appeal to it, but I totally disagree with them. I always have. It's a story about the power of the State. It's a story that forces us to challenge how far we as individuals and societies will accept that overarching power. It challenges us to take a hard look at diversity, multiculturalism and shared identity today in 2016. It's a story that forces us to understand how events in the past really do shape events of today. Several stateless people have described having citizenship and rights for most people in the world is like breathing. Just as most people breathe in and out effortlessly, the rights they are born with and have in their day-to-day lives are received effortlessly as well. Take away their air and they will find it doesn't take long to suffocate. Take away some of those fundamental rights and they will feel as if they are suffocating as well.

When people really take the time to become exposed to and understand the issue of statelessness and the stories of stateless people, they immediately want to know more and they immediately see how easy it would be in the world we live in to suffocate.

And as history has proven, given the wrong circumstances, at the wrong time, during times of extreme stress, when xenophobia and jingoism can be at their height, any of us can be vulnerable. All it takes is a government--any government--to change laws, to codify discrimination and hatred. No country is immune.

Why works of this kind are so important: such a change in circumstance, and any of us could find ourselves facing such a fate. Only by personally feeling those kinds of stakes will anything be done to make sure such basic human rights are not just accepted in theory, but also demanded in practice.

And such demands are in everyone's interest.

For Constantine, also important is the sense of humanity he has found among those who are vulnerable, and again, this is something he hopes is evident, for it is also about the capacity we have as human beings to identify with one another when the stakes are inordinately high. This is something that is an indelible part of the human experience, regardless of circumstance.

[Statelessness] is a story that at its heart reveals the strength of the human spirit to survive, of families believing in each other, of communities who are proud to identify themselves as who they are and demanding to be recognized and respected for who they are and what they have to offer others around them. Over the years I've grown more and more amazed at the sheer determination stateless people have to keep moving forward with their lives year after year with all of deprivations that have been put before them. Their ability to adapt. Their ability to find solutions. To maintain their dignity...when so much has been denied from them and when so much of their future is out of their control.

Through Constantine's photographs, perhaps an understanding of such common human emotion may indeed bridge the gap, so it's not so much a matter of "us" and "them"...but a recognition of threads that run much more deeply, connecting us to those we might not otherwise have known about, and making their rights and well-being as important as our own.

All photos from Nowhere People in this post are under copyright.Nowhere People is available via www.nowherepeople.org. For further information on Greg Constantine, please see http://www.gregconstantine.com.

A photo feature from Nowhere People will also be featured in MIPJ 2016: Refugees, IDP's and Statelessness. Further information about the MIPJ edition is available via http://www.mipj.org.