President of the UN's 70th General Assembly, Mogens Lykketoft, and Mette Holm recently spent 15 months in New York while he was in office at the UN. Since their return to Denmark in September they have co-authored a book on their experiences at the UN as well as in New York City. This is the second excerpt from the book, adapted and translated from the Danish. Very few chapters in the book were written by only one of the co-authors; this one, Chapter 19, was written by Lykketoft alone.

It came as a surprise to most that we managed to open the process of selecting a new Secretary General of the United Nation. Here too, the Security Council's permanent members had so far been opposed, and the UN's first eight Secretary Generals have been presented to the General Assembly for rubber stamping after opaque backroom dealings in the Security Council.

On October 13, 2016, the UN General Assembly elected Antonio Guterres as the UN's ninth Secretary General, effective 1 January, 2017. It was a great and moving moment: Never in the history of the UN has it been more convincing that the best man was indeed elected to become Secretary General. This was explicitly stated in all the welcome speeches; as a tribute to the Secretary General-elect, and also as praise and a result of the completely new and different election process, which I spearheaded as President of the General Assembly.

I knew Antonio Guterres from his time as Portugal's socialist Prime Minister 1995-2002 as a man of strong opinion and great vigour. Antonio also served as chairman of the Socialist International, the global association of socialist and social democratic parties. In this capacity, he led a large meeting with African leaders in Maputo, Mozambique, in November 2000, which I attended for the Danish Social Democratic Party, Denmark's governing party at the time. Guterres' close connection with Africa contributed to making him front runner in the race to become Secretary General. Most important, however, were likely his tireless and honourable efforts as UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 2005-2015, which in many countries' assessment made him the most appropriate candidate in this point in time - in a world with 65 million people displaced from their homes because of war and persecution.

The post as Secretary General is the most important in the UN. The SG is 'government' and administrative leader. The UN Charter also provides the SG with a wide range of opportunities of initiative, including to convene the Security Council and call for action against threats to international peace and security. From his - or her - position, the SG must exude moral authority and demonstrate exceptional diplomatic and political skill to unify interests and end conflicts. Furthermore, there's need for an inspired SG with ideas, courage and strength to modernise and streamline the mighty UN-machine, which suffers from too many silos and bureaucratic procedures.

If anyone can handle this seemingly impossible role at this point in time, it is Antonio Guterres.

Here's how the way was paved for his selection:

When we arrived at the United Nations in the summer of 2015, interest in the election of the new SG was already massive. Everywhere were lively discussions on how this election could be conducted in transparency and with the actual participation of all UN member states.

The views were plenty. Most consistent was the perception that a more open process would be conducive to the selection of a strong and independent personality. Many energetically advocated making UN's equality target specific by selecting the first woman as SG; and there were strong views on regional rotation, where Eastern Europe as the only region that hadn't yet delivered an SG claimed to be next in line.

Encouraged by the active and broad participation in the debate on the sustainability goals (SDGs), civil society demanded that interested citizens of the world had opportunity to discuss the candidates as well as with them, and make their views known; among them not least the new NGO 1for7Billion, an association of more than 750 NGOs who claim to represent 170 million people, and whose name expresses the requirement that the person in UN's top job is not just a pig in the middle of the big powers, but a true representative of all humanity.

The UN Charter only very briefly states that the Secretary General is elected by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council. It says nothing about the process leading up to the election, nothing about regional rotation, nor the job specific content or duration of the tenure. And the wording in the English version of the Charter is even outdated and inappropriate, clearly stating that the SG must be a man; the Russian version uses the word for human. Fortunately, in this particular case everyone agrees to interpret from the Russian version of the Charter.

Historically, the process has pivoted around the Security Council's role as 'appointment committee'. The five permanent member states' veto power in the Security Council in effect meant that it was they who must agree on which candidate to present to the General Assembly.

Negotiations on candidates have often been lengthy and opaque. And it always ended up with the Security Council bringing only one name forward, and every time with a suggested term of five years, with the possibility of extending with one more term.

So, for the first 70 years, the General Assembly's election of the SG has basically been rubber stamping a difficult birth in the Security Council.

The first eight SGs were very different personalities, who worked on the world stage under strongly changing conditions during and after the Cold War, while the United Nations membership grew from 51 to 193 states. The Security Council's five permanent members, the US, USSR/Russia, China, UK and France, seemed reluctant to nominate a strong and independent personality for the office. Dag Hammarskjöld and Kofi Annan were examples of officials, who'd been expected to keep a low profile; instead, they rose to the challenge and proved both willing and able to wrestle with the major powers.

There's nothing new in the member states' demands for real influence on the election of the Secretary General. It has been criticized that the Security Council deliberations took place in secret. Other UN member states and the world public often didn't even know whom or what the Security Council discussed - in the formerly smoke shrouded - back rooms. Even less known were secret agreements on the consecutive distribution of top posts in the UN system, in order to secure support for the various candidates. Only afterwards was it obvious that such agreements existed, and were the way for major powers to secure key posts in the UN system.

Now that Guterres has taken office, it will be interesting to see whether - or how - this system has been perpetuated.

Up until 2015 the explicit desire for a new selection process was never followed by action.

The wishes were repeated in the 69th session's final days in September 2015 with a unanimously adopted resolution on 'revitalisation' of the work of the General Assembly. The resolution called for organising an 'informal dialogue' between the General Assembly and each candidate to the post of SG.

As President of the 70th General Assembly, I was determined to push the process forward this time. The first hurdle was that according to the resolution, the process was to be initiated with a joint letter from the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council. No doubt, this was at the request of the Security Council's five permanent members in order to avoid attempts at shifting the balance of power between the Assembly and the Council.

Referring to the resolution, and without much success, I set out with a draft letter. Presidency of the Security Council rotates between members every month, and the current president can only sign a letter if all 15 members agree on the text. Russia's ambassador, Vitaly Churkin, had numerous suggestions for revising the text and little understanding of the need to change things. Like so much at the UN, for a good while it looked as if we weren't even going to get started.

In the absence of a permanent president, the Council appointed British UN Ambassador Matthew Rycroft to author the letter along with me. UK is one of the five permanent members - and Matthew is staunchly in favour of openness in the SG election. Both Matthew's team and my highly competent staff member on the issue, Meena Syed from Norway, were losing heart in the light of Russian opposition. But in early December 2015 Matthew suggested that he and Vitaly came by my office to see if the three of us together could work out a text.

My team never expected more than the meeting might enlighten us on the major obstacles of agreeing on a text. But, figuring that the actual wording of the text was subordinate to giving me, as PGA, free reins to initiate a new process without interference from the Security Council, I tried, full speed, to meet the Russian proposals. Quite remarkably, we succeeded.

Vitaly left the office saying that if this was really so important to me, then fine. No one would be interested in the procedure anyway, he said, implying that, as always, anything of importance would surely take place in the Security Council. Much to Vitaly's credit, a few months later he admitted to me that he'd been mistaken.

In my cabinet, we immediately started calling for proposals for candidates and drawing up details of the so-called informal dialogue, which was a two-hour examination of each candidate separately, transmitted live as well as subsequently around the world on the web.

Candidates were required to provide a written presentation of their vision for the United Nations and the office. During the examination, they had 10 minutes to present themselves and their vision for the UN; the rest was a dialogue with member states asking - often very specific - questions, and the candidates answering. In between we screened two or three videos with questions from civil society, which the candidate had to answer. Thousands of other questions were put to the candidates via social media, and we picked a few key questions in real time and passed them on. The candidates also participated in public meetings outside the UN and around the world.

13 candidates were put forward. Eight from Eastern Europe, including five from the former Yugoslavia and two from Bulgaria. Seven were women. I personally chaired 12 of the 13 dialogues with the candidates.

Not everyone was keen on the idea of sitting for the exam in the General Assembly, cameras rolling. A few of them - Irina Bokova from Bulgaria and Srgjan Kerim of Macedonia - tried to excuse themselves in order to avoid the very public dialogue. Considerable pressure on their advisors and their countries' permanent representatives in New York made them change their minds and participate. Most likely, the two had an inkling that they would hardly come out winners.

And most likely, other candidates too were well aware that their chances were minimal, but used the opportunity to position themselves on the international stage in order to, perhaps at a later stage, come into consideration for other international assignments. For example, it wouldn't be at all surprising, if Slovakia's foreign minister emerges as Eastern Europe's candidate for the PGA 2017-2018.

There's little doubt that the idea of a woman or an Eastern European (or both) would have stood a better chance, had the region been able to agree on a single candidate. Because Bulgaria very early on presented a female candidate, the most qualified and agreeable woman candidate from Eastern Europe, the EU Commission's Bulgarian Vice-President Kristalina Georgieva, was only allowed to enter the race a few weeks before the decision was made.

Such late arrival in the run-up would have made no difference in the past, when everything was decided shrouded in secrecy in a Security Council back room. But the new process changed conditions irrevocably: The Security Council can only consider candidates, who have been introduced in the General Assembly through the informal dialogue. When Georgieva finally arrived in the process, the party was almost over, although she, too, made it to the presentation in the General Assembly, chaired by my successor.

Most appropriately, the dialogues took place in the Trusteeship Council, which we Danes call the Finn Juhl Hall, as it was designed by the Danish architect Finn Juhl as a gift from Denmark, both originally in the early 1950es, and in the refurbished version of 2013; along with the General Assembly Hall it is one of the UN Headquarters' most magnificent rooms.

The dialogues turned out to be a true crowd-puller. All members' seats were packed, as were the staff's and visitors'. The dialogues provided an opportunity to get to know the candidates, their priorities and personalities, for the first time. And it became a unique platform for discussing the UN's major challenges, sustainable development, war and peace, respect for human rights and the need for administrative reforms. A very large part of member states' ambassadors, the US, Britain and France included, participated actively in the debates. Russia and China were present, observed keenly, but remained silent.

Further to the mandatory dialogues, along with the TV-station al-Jazeera, we organised a live broadcast of a town hall meeting between 10 of the candidates in the General Assembly Hall in July. The debate was chaired by two of al-Jazeera's excellent and experienced journalists, and all other media had free access to broadcast the debate, live or on tape, in its entirety or in excerpts.

Across the globe, acouple of hundred million people followed the debate. Afterwards it was made available on-line.

Vitaly Churkin resented the live broadcast of the town hall debate. He questioned our right to conduct a live debate, and why al-Jazeera had been given the task. I replied that all along, I had expressed the wish to present the candidates to a world-wide audience, and thus it shouldn't come as a surprise. Strangely, al-Jazeera was the only channel that felt up to the challenge, including sharing the broadcast with all other interested TV channels. 'Hopefully, you'll do no such thing again', Vitaly said. 'Perhaps,' I replied, 'and Russian television can have the assignment next time!' That was the end of that.

A number of countries wanted the Security Council to present more SG-nominees than one for the General Assembly to vote on, as well as a fixed term of seven years rather than the usual five years with the possibility of extension with another term; the latter to give the new SG greater independence from the major powers from the outset. These two proposals never came to a vote. The first paled as the wide consensus for Guterres gradually materialised. This was good, as a vote could have weakened the new leader's authority; and the new process granted the member states influence. Neither was the second proposal upheld. This may have been due to the amusing suggestion by former SG Kofi Annan, while we were having lunch: Not being able to be re-elected might sound like a grand idea to UN ambassadors in New York. But many heads of state, not least in Africa, might turn up their noses at the thought of establishing such a principle - at home or abroad! Kofi Annan, too, was full of praise for the new process for the selection of a new Secretary General.

Of the 13 candidates, Antonio Guterres made the strongest impression by far, both in his dialogue with the General Assembly and in the town hall debate with nine other candidates. This is what I believe as well as the conviction of everyone else I have talked to. Even though many of us had hoped, for the sake of equality that a woman came out best, we must also welcome the fact that the best candidate won.

There's absolutely no doubt that the dialogue and debate affected the member states' decision. And the five permanent members with veto power were more obliged than ever before to consider the opinion of their friends and allies outside the Security Council. It was perhaps the first time that the 10 countries elected by the General Assembly to the Security Council for a two-year term, felt like true representatives of the other 178 member countries and listened to their opinion. Before the process started, a cynic, who has been with the UN for several years, stated: 'It won't be Guterres. He is neither a woman, nor from Eastern Europe, and he is too intelligent and strong minded for the major powers.' Fortunately, our friend was wrong!

From July to October, the Security Council held six straw-polls. Through them all, Antonio Guterres enjoyed consistent support from the vast majority of the 15 Council members - and he was opposed by the fewest. In the first as well as the last round, no country voted against Guterres. 13 were for - including the perm five - and two neutral.

So, we crossed the finishing line with flying colours! As President of the Security Council in October 2016, Russia's Vitaly Churkin received unanimous support to nominate Antonio Guterres. And back home in Denmark, we watched when Vitaly proudly announced that Antonio Guterres had won the last straw-poll uncontested. This was a nice departure from the first five straw-polls, which obsolete forces in the Security Council desperately tried to keep secret from the General Assembly and other interested parties. Never the less, results were on Twitter within half an hour, leaked by pro-transparency members.

It was foolish to try to keep the results secret, and after the first straw-poll, I wrote as much in an open letter to the Security Council - a letter which pleased the General Assembly and reform-minded members of the Security Council.

But, this too, was history when, unanimously and in high spirits, the General Assembly accepted the recommendation of Antonio Guterres as UN Secretary General on the 13th of October 2016 with standing ovation.

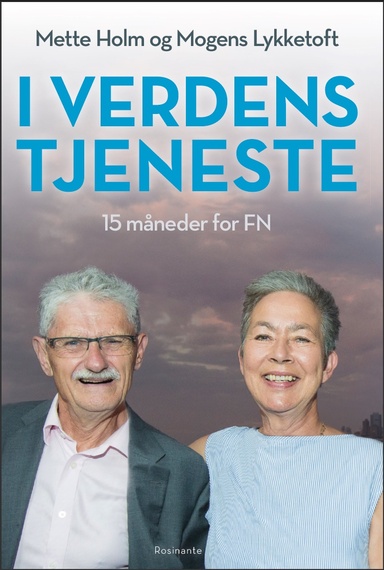

My husband, Mogens Lykketoft, and I recently spent 15 months in New York during his tenure as President of the UN General Assembly. Since our return to Denmark in September we have written a book on our experiences at the UN and in New York City, I Verdens tjeneste (Serving the World), published in December 2016 by Rosinante & Co. The above is from chapter 19. We hope to have the book published in English in the near future. This is our third co-authored book; the first was on China (2006), the second on Myanmar (2012)

Read the first translated excerpt from 'I verdens tjeneste - 15 måneder for FN' (Serving the World - 15 months for the UN), Trump's United States may be a threat to United Nations.

Mogens Lykketoft is on twitter: @lykketoft