More than two years after conservative Texas legislators cut funding of family planning clinics by two-thirds, a report has revealed just how devastating the cuts have been for the welfare of many women who now no longer have access to contraceptives, pap smears, life-saving cancer treatments and other critical services.

Specifically, the report, compiled by the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health (NLIRH) and the Center for Reproductive Rights, looks at how the cuts have affected one of the most under-served communities in one of the poorest areas in the state: Latina women living in the Rio Grande Valley, an impoverished area in South Texas that borders Mexico.

According to the findings, which are part of a human rights campaign called "Nuestro Texas," the state has not just failed to provide critical health services to its people, but it has actively infringed on their basic human rights.

"The idea behind the [2011] cuts was to attack and undermine Planned Parenthood and prevent abortions," Katrina Anderson, human rights counsel for the Center for Reproductive Rights, told The Huffington Post. "But these efforts are destroying women's lives. It's about so many other issues that have nothing to do with abortion."

Across the state, an estimated 147,000 low-income Texas women have lost access to preventive care as a result of the cuts, according to the Texas Academy of Family Physicians. But Latinas -- especially those living in poor and rural areas with large immigrant populations like the Valley -- have been disproportionately hard-hit, the report's authors say.

Map of the four counties that comprise the Rio Grande Valley. About 1.3 million people, mostly Latino, live in the Valley.

"Women in the Valley no longer have the basic freedom to get a mammogram or to get checked for a sexually transmitted infection," Lucy Felix, a 43-year-old mom and grassroots organizer for the NLIRH, told HuffPost. "There's always been poverty here, but before 2011, there were some programs and some access to care. Now there's still poverty but there are no more programs."

After the 2011 cuts, nine out of 32 family planning clinics in the Valley funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) shuttered their doors, and those that are still open have significantly slashed their hours and services. According to a November report by NBC News, it can now take "many months to get an appointment" at a clinic in the Valley.

Lack of health insurance and substandard public transportation also means that it can be very difficult for women to find clinics to seek care. "Women have nowhere to go," Anderson told the HuffPost.

Moreover, less funding has meant a significant reduction in subsidized services. Before the cuts, for instance, clinics offered annual exams to uninsured women for a subsidized rate of $10 to $25; today, however, those figures have skyrocketed to between $60 and $200, per the report.

As a result of these higher fees, women in the Valley -- some of whom live "in extreme poverty," says Anderson -- can no longer afford these services, even when they desperately need them.

"It's $60 for a checkup. I thought, either I pay $60 or I buy food for my children," said Ida, a single mother-of-two who has human papillomavirus (HPV), a key risk factor for cervical cancer, according to a post on the Nuestro Texas website. "Being unable to see a doctor has me worried sick."

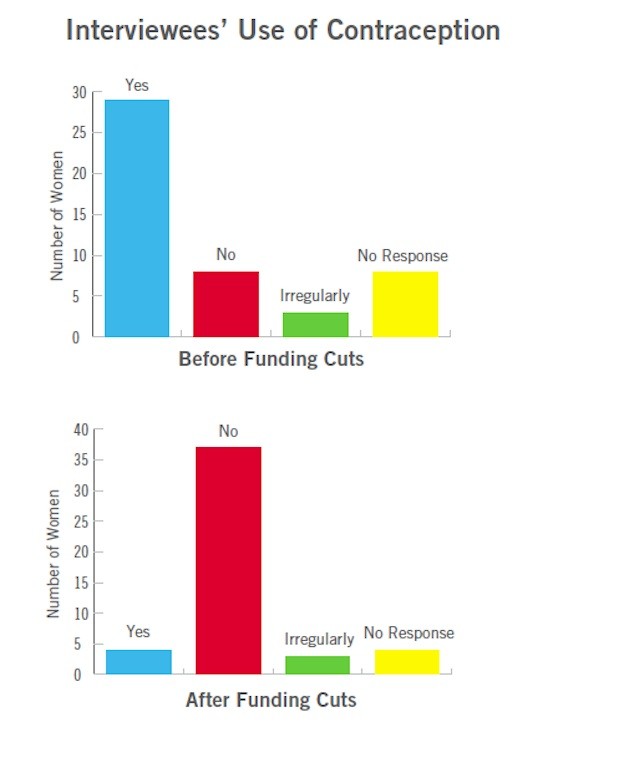

Contraception is now also often too expensive for a majority of women in the Valley, per the report. Two-thirds of women reportedly can't afford to pay for contraception without assistance, and many of those interviewed for the report said they had stopped using contraception since the cuts.

For undocumented women in the Valley, the situation is even more dire. As funding has shrunk, clinics are reportedly demanding more paperwork from patients so that they can prioritize citizens and residents for subsidies. In addition, more checkpoints have been erected, thereby preventing undocumented women from venturing too far from their communities to find care.

"If I get sick, I don't know what I'm going to do," Adriana, an undocumented Mexican citizen who is the sole caretaker of her two young grandsons, said in a heartbreaking video posted on the Nuestro Texas website. "Mexico has become a country with too much kidnapping, too much violence. For my grandchildren, I find myself here. They depend on me."

Watch Adriana's story here:

Still, despite the overwhelming challenges facing them, the women in the Valley have refused to take their setbacks lying down.

Felix told The Huffington Post that women in the Valley have been mobilizing in recent years. They attend rallies and marches calling for improvements in transportation access and the restoration of funding to the clinics. Many have also reached out to state and community leaders to call for change, attending legislative visits and participating in letter-writing campaigns.

Felix says that she believes that the community's organizing efforts have ensured that "all the funding hasn't been cut."

In addition, women in the community have been actively filling the health care void themselves. Every month, as part of the Latina Advocacy Network, NLIRH’s organizing arm in Texas, women throughout the Valley and elsewhere in Texas, including cities like Houston and San Antonio, meet in small groups to discuss their reproductive health and their rights.

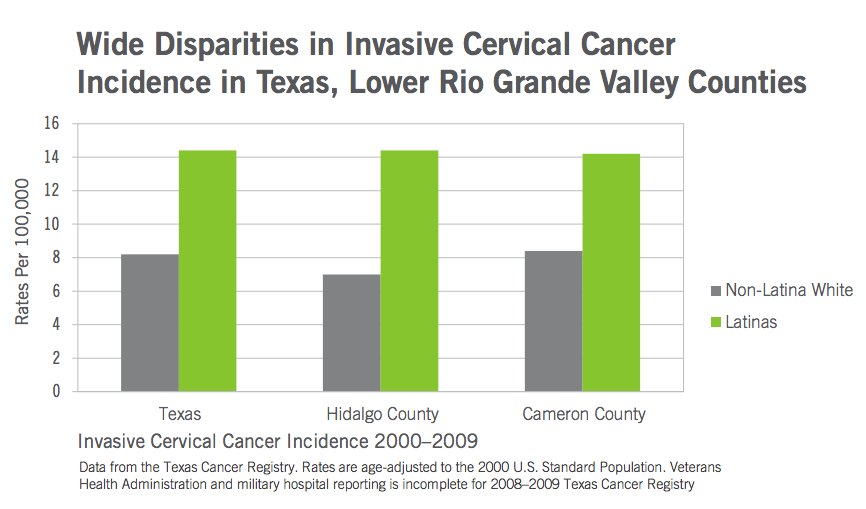

In January, for instance, the groups discussed cervical cancer prevention (Latinas in Texas are "nearly 36 percent more likely to die of cervical cancer than white Texans, and 26 percent more likely to die of cervical cancer compared to Latinas nationally, per a 2013 NLIRH report).

"By engaging in this grassroots work, women find pride in themselves and begin to live dignified lives," Felix told the HuffPost. "Regardless of their status, their wealth, whether they have documents or not, they learn that they are powerful. They learn how to be advocates for themselves, for their children, for their community."

Ultimately, activists say they hope the Nuestro Texas report -- which Anderson says will be brought before the Human Rights Committee in Geneva next month and to Capitol Hill later this year -- will force Texas to take responsibility for its actions and serve as a warning to legislators across the country.

"We want the [Texas] legislature to address many of the concerns and fix the problems that they've created," Anderson said. "Texas is the epicenter of bad reproductive health policy and it's also the incubator of it. Oftentimes, policy proposals that Texas implement get replicated elsewhere. We hope to show that Texas' experiment with family planning has been an economic and rights disaster in the State."

Last year, Texas legislators said they were restoring family planning funds by ear-marking $100 million for a state-run primary care program specifically for women's health services, among other changes, in the hopes of addressing a growing reproductive health crisis. (The Population Institute recently gave Texas a grade of "F-" on its 2013 reproductive health and rights record). The jury, however, is still out as to whether these funds will actually reach the women who need them.

Until these needs are met, Lucy Felix says that the women in the Valley will not stop fighting.

"I won't stop, the community will not stop," she said. "We'll continue fighting until we're able to achieve justice, human rights and change."