When Mike Bloomberg continued and accelerated Rudy Giuliani's move to break up traditionally large high schools in favor of smaller schools, he began to radically restructure the city's educational system. Touted as a reform to a large, inefficient high school model, the move meant breaking up existing high schools by lowering reform axes down on underperforming schools, as judged by the city. Poor communities of color became the epicenters of the small school experiment and today the byproducts of the education chopping block can be found where multiple schools are housed in a single building that might've someday been one large high school.

"It was absolutely racist", says Norm Scott. Scott is a retired teacher and a veteran education activist with the Movement of Rank-and-file Educators (MORE-UFT), a caucus within the United Federation of Teachers. Scott says the move to chop up big schools and create a lot of smaller schools was a union-busting strategy that started under Giuliani but that really picked up steam under Bloomberg and former schools chancellor Joel Klein. "It's part of the education 'deform' movement", Scott says, referring to reforms that have been criticized as thinly-veiled efforts to privatize public education and weaken the teachers union. "The union was strongest in large high schools. Chop them up and chop up union power at the school level--leave the head with no body."

Deborah Meier, a former teacher and one of the early advocates for smaller schools--known nationally as the Small Schools Initiative, believed that small schools could bring teachers closer and encourage democratic decision-making at the school level. But she's critical of how the model has played out in New York:

"The people who are breaking up the big high schools in New York -- which I was all for -- are now using it to privatize public schools and not to create more democratic communities. It is painful to watch. Today, the word autonomy means frightened principals who now have more power over their frightened teachers, which can't help but lead to frightened kids and families. Those at the top now have more power to intimidate."

Microsoft's Bill Gates, a target of anti-privatization voices, has been a key supporter and funder of the small schools push. Indeed, criticisms of small schools run parallel to those made against charter schools, the hotly debated, privately-managed public schools whose powerful advocates include hedge-funders and foundations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Small high schools also often pay to belong to an education network, a third party that offers curriculum and management services, not unlike charter management companies (though not as influential, politically, like Eva Moskowitz' Success Academy chain). In both cases you have an added layer of bureaucracy that can blur the public-private line in education.

The complicated, highly politicized machinations of small school reform also helped to make nearly impossible something that should've been a no-brainer: equality in school sports.

The move towards the small school model also meant creating new schools, usually designed for only a few hundred kids. Newly-minted small high schools started popping up across the city. Sometimes they'd be in their own building but more often than not they'd share space with an elementary school, middle school, or even be housed in an office building. These new small high schools didn't have a campus that could support a robust sports program, either. So while chopped-up small schools operating one roof could sometimes field a team under a single banner, sharing resources and bodies, the newer small schools couldn't. The Bronx is littered with small schools like this--International Community HS is one them.

David Garcia-Rosen was the dean at International High School in the South Bronx. He says that today's small schools, like International, which primarily serve students of color in the city, have been given the short end of the stick in the Public School Athletic League's system for at least the last fifteen years. He has helped to organize a student-led campaign called NYCLet'EmPlay. The group has been speaking out and protesting a lack of equal sports access, recently disrupting Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña's by dropping a banner reading "Civil Rights Matter" at the city council earlier this year. Garcia-Rosen was suspended and removed as dean the day after that action.

International had no sports teams before he and others created an alternative league from scratch: the Small Schools Athletic League. The league ran for three, by all accounts, successful seasons. Though funded initially by school principals directly from the school's budget, Garcia-Rosen managed to squeeze funding from the Department of Education in 2013. Legendary Yankees closer Mariano Rivera even presented trophies to student-athletes at the SSAL's "Power of Sports Awards" ceremony in 2014.

Garcia-Rosen figured the SSAL could fill in the gaps where the PSAL wouldn't or couldn't provide sports access for small schools like International. He had tried and failed to get International a PSAL baseball team in 2011. The PSAL told him that his school, at just above 400 students, probably couldn't field enough players to form competitive teams. In the SSAL, International's baseball team was huge success, winning the league title in 2013 and 2014.

This is where Garcia-Rosen points the finger squarely at the PSAL and it's leadership. What he describes as an arbitrary process, the granting of sports teams by the PSAL, are the actions of an agency completely unaccountable to students--students of color in particular. In fact, when he began piecing together the SSAL in 2011, reaching out to principals and athletic directors, he'd get enthusiastic reactions from school leaders who'd also been snubbed by the PSAL. One small school principal in Manhattan described the PSAL as "ossified and outdated" in an email exchange with Garcia-Rosen and a PSAL staffer who had responded to the principal's application for a PSAL football team by warning him of the costs associated with the sport, trying to dissuade him from applying. In most cases the PSAL simply rejects applications with a generic letter citing things like "budgetary restraints" as a reason for denial.

The popularity of the SSAL was very much a reflection of a broader frustration with the PSAL for a lack of sports opportunities in the poorest parts of the city. Garcia-Rosen's research on this is staggering. About 80% of small school students are at a school that is underfunded or isn't funded at all by the PSAL. This problem is one almost exclusively one for poor students of color. Staten Island, which already receives nearly double the PSAL funding than that of the Bronx, gets more teams from the PSAL as well. In 2013, 78% of new PSAL teams went to schools with the lowest percentage of black and Latino students.

In 2010, a federal title IV complaint said that girls, including those in New York, were being disproportionately left out of school sports. The PSAL temporarily stopped creating boys teams until 2012 when Queens councilmember Elizabeth Crowley leaned on the league to create new boys teams for Maspeth and Metropolitan High Schools. Maspeth and Metropolitan, high schools in solidly middle-class Queens, are both larger and whiter schools than International. Today they both enjoy nearly 20 PSAL sports but serve only 2% and 4% Black students, respectively. In contrast the with failed efforts by International and others to get teams for their school, it seemed the PSAL was susceptible to political pressure.

DOE leadership, for its part, has been keen to announce expansions to its school sports repertoire. In April 2014 chancellor Fariña, appearing alongside actress Susan Sarandon, announced table tennis and badminton were being added to the PSAL's portfolio. But, as one reporter pointed out, the "schools selected to add new sports teams aren't exactly ones with a dearth of athletic options in the first place." The schools getting the new sports were mostly larger schools, including Tottenville High School in Staten Island, which now boasts 44 sports--the most in the city. Still, the press release raved about the new sports, regardless of where they were going.

For the past few years Garcia-Rosen has met with all sorts of characters over the years to raise awareness and look for a solution: low-level political staffers, community boards, high-ranking DOE officials. Initially he had tried working directly with DOE officials in both the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations to discuss fixing the PSAL's racial blind spots. At the end of one long meeting with DOE decision makers in April 2013, a frustrated Eric Goldstein, CEO (Yes, CEO) of of the Office of School Support Services, which oversees the PSAL, made one thing clear to Garcia-Rosen:

"There will be no Marxist redistribution of sports teams in New York City."

Eventually, the PSAL did try to offer Garcia-Rosen a job. Without a real plan in place, though, the job simply looked like a buy-out of the vocal dean and history teacher. He rejected the offer.

Last year the PSAL put out a letter announcing the "new" Small Schools Athletic League, which included two levels: the Developmental Division and Multiple Pathways League. The SSAL, of course, was not new. Garcia-Rosen had started the SSAL. But by securing $825,000 in funding for it from a seemingly sympathetic city council in 2014, the stakes had grown and the PSAL snatched up the name, seeking the funds that had been allocated for SSAL. The original SSAL schedule was cancelled while sports like soccer and baseball were replaced by table tennis.

It was Garcia-Rosen's worst nightmare: the DOE had co-opted the SSAL and and brought it under umbrella of the PSAL. He and his students were now on the outside looking in. This made it clear to Garcia-Rosen and others that at its core the issue wasn't simply one of funding--it was one of control. If the PSAL had managed high school sports in a way that was intentionally or unintentionally leaving thousands of students with little to no sports, then what good would it do to bring this alternative league under its leadership?

With an inexplicable paranoia about Marx, Bill de Blasio and Carmen Fariña''s Department of Education hasn't made any moves to fix these problems. The 'progressive' mayor and a largely useless city council have largely ignored the issue--allowing the PSAL to swallow up the SSAL. Goldstein, a holdover from the Bloomberg administration is the embodiment of the saying: Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. And all of this leaves Garcia-Rosen and the students from the NYCLet'EmPlay campaign fighting both the ghosts of the small school reform era as well as today's city hall.

We should all stand behind them.

NYC Let 'Em Play outside City Hall this year (credit: NY Observer)

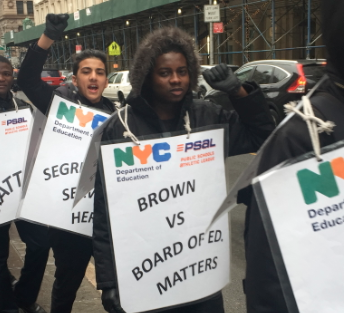

NYC Let 'Em Play outside City Hall this year (credit: NY Observer) Students picketing outside Tweed courthouse, Dept. of Education headquarters

Students picketing outside Tweed courthouse, Dept. of Education headquarters Students from International Community High School in the Bronx

Students from International Community High School in the Bronx