The world is out of control; or is it?

Barack Obama understands something most of us do not. Those of us who watched his speech last night, and who grew up in the half-century where America seemed to direct the world's affairs, are used to the following equation: a problem appears in the world; the American president takes action; if he acts correctly, the problem is solved.

Leave aside that America's power was never that absolute, that our alliances and achievements were always more fragile and partial than we wanted them to be: we don't live in that world anymore, and it hurts. This powerlessness makes us angry, and we transfer our anger and disappointment to the man who -- last time we checked -- is still the most powerful human being on earth.

To understand what Obama understands is to recognize what lies in our power, as human beings and as nations, and what lies outside it. My advice: if you want to understand America's president, read a Roman slave.

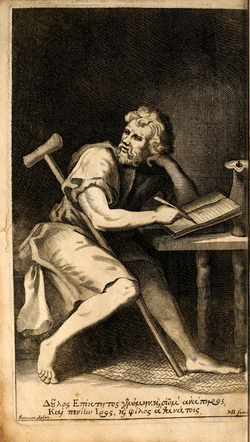

Ex-slave, to be precise. The philosopher Epictetus, who led a school at Nicopolis in the second century AD, knew about the feelings America struggles with today.

Rome had conquered the world as a citizen-republic, but civil wars and the rise of the Caesars had transformed this world of citizens to a world of subjects, who lived and died at the nod of men like Caligula and Nero. Civis romanus sum, the proud declaration of a citizen in the world's most lawful and powerful state, ran against the fear and powerlessness of daily life under a tyrant's rule.

This struggle -- how to reconcile our pride with our powerlessness -- is the one America confronts in the 21st century. What Obama understands, and his critics do not, are Epictetus' three most important lessons.

1. Know what is in your control, and what is not.

Epictetus begins with the Stoics' basic picture of how we interact with the outside world: the world gives us impressions (fantasiai); we then decide (prohairesthai) whether to assent to these impressions or reject them. E.g., that Starbucks carrot-cake muffin sends me a delicious impression; I decide whether or not to assent to it and break my diet.

Epictetus' contribution to this tradition was to take this moment of decision, the prohairesis, and raise an entire ethical system around it. He divides everything in our universe into two categories: the many things we can't control (ta aprohaireta), and the one thing we can, our prohairesis, what English-speakers would later call free will.

Does this mean that the scope of our powers are vastly reduced, that we are weak shells of the people we thought we were? Precisely the opposite. In cultivating our power to assent or reject impressions, we cement the one power truly available to us, and it is indomitable: "It's only my leg you will chain," says Epictetus in the Discourses, "not even God can conquer my will." (1.1.23)

True freedom, in other words, lies not in controlling the world around you, which is impossible, but remaining in control of yourself, which is merely very hard. This duty to correctly judge and react to events is, for Epictetus, the whole philosophical ball game:

"Whenever we do something wrong, then, from now on we will not blame anything except the opinion on which it's based...Wife, child, slave or neighbour: in the future we won't name any of them as authors of the evil in our lives, in the knowledge that, unless we judge things in a particular light, we won't act in the corresponding manner. And we, not externals, are the masters of our judgments." (1.11.35-37)

Americans want our president to be all-powerful because we see him as a metonymical extension of ourselves: if the most powerful man on earth can't solve Ebola or make Vladimir Putin and ISIL disappear, how much more terrifyingly powerless must we be?

So Obama's critics believe, or pretend to believe, that if he just "projected strength," or "aggressively confronted" America's enemies, that these problems would go away. This is, to borrow another Stoic term, childish thinking. Obama's approach -- to reflect before reacting, to build coalitions, to treat different nations differently and recognize the limits of American control -- is mature.

2. Do your duty, and fear no tyrant.

You've heard it everywhere: democracy is in the doldrums, tyrants are on the march. Putin and Assad look indomitable; Islamic fascists are gaining ground; Obama and Europe are weak.

Is this true? It depends, says Epictetus, on what strength and weakness really are. Many of the President's critics measure American power by our capacity to control wealth, territory, and the actions of other global actors. Epictetus was familiar with this kind of thinking: "Here we find robbers and thieves, and law-courts, and so-called despots who imagine that they wield some power over us precisely because of our body and its possessions. Allow us to show them that they have power over precisely no one." (1.9.15)

When we measure our power as the power to kill or control territory, we give tyrants like Putin and ISIL the upper hand. When we measure power as the power to act with humanity, solidarity, and courage, then America is, as we want it to be, the strongest nation on earth.

"Walk upright and free," urges Epictetus, "trusting in the strength of your moral convictions, not the strength of your body, like an athlete. You weren't meant to be invincible by brute force, like a pack animal. You are invincible if nothing outside the will can disconcert you." (1.18.20)

This is not a philosophical magic act: tyrants do not disappear, and dead Syrian children do not come back to life. Evil exists, and must be resisted, tirelessly and fiercely. Last night President Obama reaffirmed America's duty to "stand with people who fight for their own freedom...[and] rally other nations on behalf of our common security and common humanity," and he is backing these principles with serious and risk-laden action.

Epictetus' insight is that those who, like Assad and Putin, stake their power on military prowess or oil reserves, will watch their fortunes change as those externalities fall away. Ultimately, tyrants are worthy not of our fear but our contempt: "When you stand before one of those tyrants, just bear in mind that you are in the presence of a tragic figure -- and not the actor, either, but Oedipus himself." (1.24.18) Obama's critics say the president isn't exerting his will because he isn't dropping bombs, or announcing a strategy before one exists, or making threats to these dictators. Obama is exerting a different kind of will, the will to act with integrity, to refuse to become one's enemy, to withhold judgment: will as Epictetus invented it.

As we resist evil, Epictetus urges us never to lose sight of the ignorance and weakness that lie behind evil acts. The philosopher Slavoj Žižek argued recently in the New York Times that ISIL is not "fundamentalist" in any real sense. Citing the barbarism and sexual violence wrought by these "Islamic" actors, he argues, "in contrast to true fundamentalists, the terrorist pseudo-fundamentalists are deeply bothered, intrigued and fascinated by the sinful life of the nonbelievers. One can feel that, in fighting the sinful other, they are fighting their own temptation."

Against the calls of a noisy few, Obama correctly refuses to frame America's policy as a clash of civilizations or religions; despite their 8th-century rhetoric, ISIL's terrorists are opportunists whose belligerent acts belie an inner weakness, proved by their inability to gain the support of those they "rule." America cannot determine when they will fall, but we can do what is in our power to bring it about, and fall they inevitably will.

3. Your integrity is your only real possession.

It is easy to forget, six years into Barack Obama's presidency, what a rare kind of world leader he is. His tenure has been marred by no personal scandal or infidelity; his critics' malevolent caricatures border on the ridiculous; and his supporters' disappointments are due far more to mismanaged expectations and poor results (e.g. Guantanamo, NSA, and immigration) than they are to malevolence or impropriety.

And yet, disappointment and discontent reign in the heart of the free world. America seems to have lost its hold on world affairs, and Obama -- careful, cerebral -- doesn't seem to care. Perhaps Obama, like Epictetus, measures victory and tragedy another way:

"Did Paris' tragedy lie in the Greeks' attack on Troy, when his brothers began to be slaughtered? No; no one is undone by the actions of others. His tragedy lay in the loss of himself, the man who was honest, trustworthy, decent and respectful of the laws of hospitality. Wherein did Achilles' tragedy lie? The death of Patroclus? Not at all. It was that he gave in to anger...and lost sight of the fact that he was not there for romance but for war. Those are the genuine human tragedies, the [true] city's siege and capture -- when right judgments are subverted; when thoughts are undermined." (1.28.22)

Americans of the late 20th century were used to having it both ways: the better ideas and also the better cars in our driveway. What the 21st century is making us choose is which of these things -- material dominance, or immaterial principles -- are nearer to America's soul. When we wage war on false pretense, or militarize our police force in the name of public order, or balance budgets by defunding food stamps, we make one kind of choice.

Like Epictetus, Obama has made another choice, as he reaffirmed last night: "Our own safety -- our own security -- depends upon our willingness to do what it takes to defend this nation, and uphold the values that we stand for -- timeless ideals that will endure long after those who offer only hate and destruction have been vanquished from the Earth."

Our times force us to confront uncomfortable truths: we wish that America could on its own create peace in Gaza, make Iraq's factions work together, and thwart Russian aggression. Being the indispensable actor, however, does not make us an omnipotent one.

Acting prudently, leveraging influence where we can, and limiting risk where we cannot: such a stance makes America's well-spoken hawks and absolutists foam at the mouth. ("God save me from fools with a little philosophy," quips Epictetus at one point, "no one is more difficult to reach." (2.10.14)). But history will show that Barack Obama's clear-eyed pragmatism was not only the prudent way to govern, but -- as the old philosopher would agree -- the moral one as well.

In the end, Epictetus advises, America should not confuse trouble with misfortune. To the contrary, he insists, "the true man is revealed in difficult times." (1.24.1) His final exhortation to us is worthy of a national address in primetime:

"Steady now, poor man, don't let impressions sweep you off your feet. It's a great battle, and God's work. It's a fight for autonomy, freedom, happiness, and peace...Put away the fear of death, and however much thunder and lightning you have to face, you will find the mind capable of remaining calm and composed regardless." (2.18.27)

America's greatness is not something that dictators or terrorists can threaten. It lies within us, and it was on full display last night in the conscience and resolve of our nation's president, of whom we all -- Epictetus included -- should be proud.