Barack Obama is riding the leading edge of a Democratic wave, benefiting from a potential -- although by no means certain -- cyclical shift in the partisanship of American voters which could last at least through 2016, if managed carefully.

Extensive studies of past elections by scholars show that there is an ebb and flow in patterns of partisan dominance, periods during which a majority of the public is inclined -- not guaranteed -- to vote for the more liberal Democratic Party, and then shift back to the more conservative Republican Party.

These cyclical shifts do not assure the election of a president of one party or the other, but they do reflect changing political climates favorable to one partisan coalition or the other.

By most accounts, the timing in 2008 is ripe for Democrats.

"All regimes overshoot what the electorate wants in their policy behavior to satisfy both their own internal ideologies and their party base, and thus sow the seeds of future opposition," said University of North Carolina political scientist James Stimson, citing as two examples the administrations of Lyndon Baines Johnson and George W. Bush.

"From this point of view, Bush's current low standing isn't only a response to what he has done, but is also the cumulative response to almost 8 years of policy excess in governance," said Stimson, who, together with Columbia's Robert Erikson and the University of North Carolina's Michael MacKuen, is the co-author of the innocuous sounding but ground-breaking book, The Macro Polity.

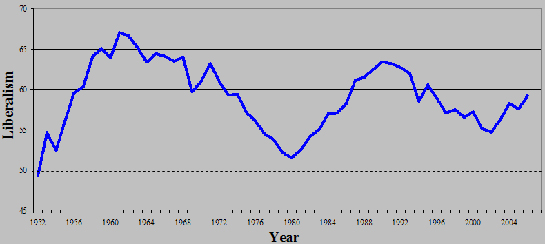

Stimson has graphed what he calls the ideological "mood" of the country, in terms of liberalism, from 1952 to the present and found the following:

Three other political scientists, Samuel Merrill, III, Bernard Grofman and Thomas L. Brunell, expanded on The Macro Polity and other research by Stimson in a February 2008 essay for American Political Science Review, titled, "Cycles in American National Electoral Politics, 1854-2006: Statistical Evidence and an Explanatory Model."

Three other political scientists, Samuel Merrill, III, Bernard Grofman and Thomas L. Brunell, expanded on The Macro Polity and other research by Stimson in a February 2008 essay for American Political Science Review, titled, "Cycles in American National Electoral Politics, 1854-2006: Statistical Evidence and an Explanatory Model."

Merrill, Grofman and Brunell, in a long-term study of House, Senate and Presidential elections dating back to 1852, found regular patterns of shifting control of the House, Senate and Presidency.

They write, "when a party first attains a majority in Congress and/or the presidency, it is likely to stay in power -- first rising then falling in seat share -- for 12 to 15 years before ceding majority status to the other party, which then enjoys a similar predominance for 12 to 15 years." Their findings and accompanying charts can be found here.

The article carries significant political implications. "If you believe the model is fully predictive, it [2008] does look a Democratic year," Brunell, of the University of Texas in Dallas, said in an interview. "It's time."

Brunell stresses the point that the cycles represent shifts in the political climate favoring one party or the other, rather than the more substantive and relatively fixed partisan commitments found in such realigning elections as those of 1896 or 1932.

Similarly, in a paper prepared by Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson for delivery at the April 2008 Midwest Political Science Association, "The Macro Polity Updated," the authors concluded:

"As of 2008, the relevant time series show a rare convergence of Democratic macropartisanship and liberal mood. These can be traced to the president's persistent unpopularity and conservative policies. According to our modeling, the result should be a presidential victory for the Democrats and (as begun in 2006) Democratic control of the House and Senate."

The authors caution, however, that "election outcomes are stochastic processes [containing random, unpredictable variables], so this prediction is no 'lock.'"

On-the-ground evidence supporting the thesis that the country is at the beginning of a Democratic cycle includes poll data showing a significant movement away from the GOP and toward the Democratic Party in the allegiance of voters, as well as a widespread assessment that Democrats appear certain to pick up seats in both the House and Senate.

The growing salience of relatively shorter cycles may result from the fact that both parties and their strategists have much more access to information -- feedback -- about their liabilities and strengths through polling, focus groups and a host of other mechanisms to analyze public opinion.

This information, in turn, enables party leaders and strategists to adjust much more quickly to changing political environments.

Looking at the issue of partisan strength from this point of view, University of Maryland political scientist Geoff Layman argues that the Republican Party is on a downswing and needs to re-evaluate both policy and strategy in order to return to competitiveness:

"The GOP and the conservative movement in general have lost a bit of steam and need to find a way to reshape their issue agenda for a changing world and a changing set of attitudes and demographics within the U.S. Maybe the best way to say it is that conservatism needs to be revamped or modernized to become better a better fit with a changing American society."

Princeton's Nolan McCarthy contends that "it's too early to say that there will be a swing to something approximating Democratic dominance," although he, and most others interviewed, believe that odds favor an Obama win.

McCarthy argues that it will take more than a cyclical shift for the Democrats to become ascendant -- it will also require skill:

"If Obama governs from the center and doesn't screw up, the Democrats will be the majority party. If he governs from the left and/or makes a big mistake, they won't be. In a lot of ways it will be like 1993. Had Clinton governed differently, there would have been no 1994 and the Democrats would have regained all of their Reagan-era losses. But he did gays in the military and let Hillary do health care. You know the rest of the story."