The Green New Deal is finally taking form.

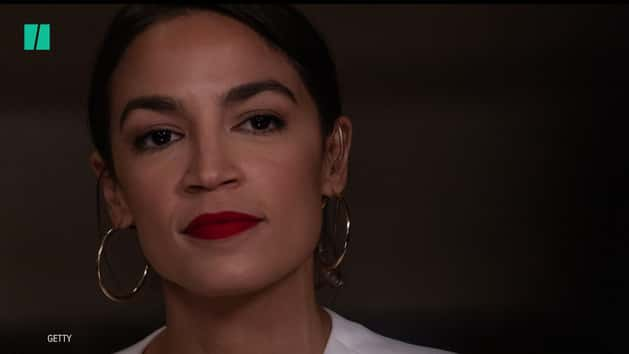

On Thursday, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) unveiled a landmark resolution cementing the pillars of an unprecedented program to zero out planet-warming emissions and restore the middle-class prosperity of postwar America that the original New Deal helped spur.

Just three months after calls for a Green New Deal electrified a long-stagnant debate on climate policy, the Democratic lawmakers released the six-page document outlining plans to cut global emissions 40 to 60 percent below 2010 levels by 2030 and neutralize human-caused greenhouse gases entirely by 2050.

“Today is a big day for workers in Appalachia,” Ocasio-Cortez said Thursday at a press conference in Washington, D.C. “Today is a good day for children who have been breathing dirty air in the Bronx.”

It’s an ambitious, if measured, clarion call for action that, if accomplished, would transform the United States into the leader in decarbonizing and clear a path forward for the world to avert catastrophic warming.

The joint resolution stakes out a “ten-year national mobilization” plan to build “smart” grids and rapidly increase the share of American power generated from solar and wind from 10 percent today to as close to 100 percent as possible over the next decade. The plan reframes tired talk of repairing the nation’s crumbling bridges, highways and ports as a crisis in a new era of billion-dollar storms. It gets local, demanding upgrades to “all existing U.S. buildings” to “achieve maximum” efficiency with energy and water use.

That holistic framing extends to the way the document describes emissions, mentioning “carbon” just once and instead using the term “greenhouse gases,” which includes methane, nitrous oxide and ozone.

Energy and infrastructure issues are the centerpiece of the resolution, with explicit goals of overhauling the transportation sector ― the country’s biggest source of climate pollution ― to expand public transit and high-speed rail and to spur a “clean” manufacturing boom with a particular focus on electric vehicles.

But, unlike most existing Green New Deal concepts, food and water are focal points. The resolution proposes “building a more sustainable food system that ensures universal access to healthy food” and “guaranteeing universal access to clean water.” To meet those goals, the document describes “working collaboratively with farmers and ranchers” to reduce agricultural pollution with “sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health” and “supporting family farming.”

Unabashedly progressive ideals anchor the resolution. A section outlining guidelines for future Green New Deal bills reads like a laundry list of populist policies, including everything from ramped-up antitrust enforcement ― “ensuring a commercial environment where every businessperson is free from unfair competition and domination by” monopolies ― to a vastly expanded social safety net, “providing all people of the United States high-quality health care, affordable, safe and adequate housing, economic security, and access to clean water, air and healthy and affordable food, and nature.”

Yet the resolution seems designed for broad appeal. The fact that Markey, a liberal stalwart who co-authored the last major climate bill Democrats tried to pass in 2009, is the lead Senate sponsor shows the insurgent Ocasio-Cortez wing is building bridges with the old guard.

The resolution itself avoids controversial technologies to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, instead calling for low-tech solutions, such as large-scale preservation and planting new forests to absorb carbon already in the atmosphere. In a news release, Ocasio-Cortez’s team said carbon capture “technology to date has not proven effective.”

The resolution contains more obvious compromises. In a departure from the initial protests that gave rise to the Green New Deal, the document avoids explicitly calling for ending fossil fuel development. It leaves open the possibility of keeping existing nuclear power plants in place until after the initial 10-year mobilization plan is complete, admitting that “we are currently unsure if we will be able to decommission every nuclear plant that fast.”

“The resolution is silent on any individual technology which can move us toward a solution on this problem,” Markey said at the press conference. “This is a resolution that does not have individual prescriptions in it.”

“We are open to whatever works,” he added later.

Bucking the prevailing bipartisan orthodoxy on climate policy, the resolution makes no mention of pricing carbon. The release stated that the “door is not closed for market-based incentives or a diverse array of policy levers to play a role in the Green New Deal, but it would be a small role.”

To supporters, those candid admissions showed that the document represented a feasible first step toward legislation.

“This is how green socialists will govern,” said Greg Carlock, the researcher at the think tank Data for Progress, whose Green New Deal blueprint from September resembles the resolution. “It will be thoughtful, it will be politically pragmatic, it will still be ambitious.”

The resolution dropped with poignant timing. During his State of the Union address Tuesday, President Donald Trump ignored climate change and touted a fossil fuel agenda projected to put the world on course for cataclysmic warming, analysis by researchers at more than a dozen environmental groups projects found. On Wednesday, House Democrats kicked off two hearings on climate change less than two hours before NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared 2018 the fourth-hottest year ever recorded.

That doesn’t necessarily improve the resolution’s prospects of passing. The GOP controls the Senate, and Republican opposition to the Green New Deal started to crystallize at Wednesday’s hearings.

Even among Democrats, who control the House, support is far from guaranteed. By Thursday morning, the resolution garnered more than 60 House Democrats and at least nine Senate Democrats signed onto the resolution. But in a Politico interview, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi dismissed the Green New Deal as “the green dream or whatever they call it, nobody knows what it is.” Environmental groups including Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace issued statements that tempered their support by calling for explicit fossil fuel phase-outs.

The sort of Green New Deal the resolution describes poses an existential threat to entrenched, deep-pocketed industries that donate to Democrats. Building a constituency powerful enough to challenge fossil fuel producers, automakers and utilities requires support from the labor movement.

Yet the influential building-trade unions are skeptical of any policy that impedes fossil fuel infrastructure, a reliable source of lucrative contract jobs. The resolution aims to ease those worries, “ensuring that Green New Deal mobilization creates high-quality union jobs that pay prevailing wages, hire local workers, offer training and advancement opportunities and guarantee wage and benefit parity for workers affected by the transition.”

But that rhetoric isn’t new, and it does little to assuage festering concerns. Renewable energy jobs tend to pay less and use fewer unionized workers than pipeline or coal-train gigs. The problem, too, is the steady erosion of labor laws over the past few decades, diminishing hopes that clean-energy work could easily reach wage parity with fossil fuels under existing statutes. A Green New Deal, in that sense, necessitates changes to labor law almost as dramatic as those governing energy and infrastructure. To that end, the resolution directly calls for “strengthening and protecting the right of all workers to organize, unionize, and collectively bargain free of coercion, intimidation, and harassment.”

The potential opposition from building trades hasn’t made the Green New Deal any less popular with Democrats’ swelling pool of 2020 contenders. Nearly every declared and likely candidate ― former Vice President Joe Biden is a notable exception ― has offered an endorsement of the Green New Deal in some form or another.

Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), who threw his support behind the Green New Deal resolution last week, is one potential candidate. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) backed the Green New Deal in December, tying support for its climate goals to a jobs guarantee bill he already introduced. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) last month sent a letter to the Republican in charge of the Senate Environment and Public Works committee outlining her support for a Green New Deal. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a likely frontrunner when he declares his candidacy, is considering legislation of his own on a Green New Deal.

Others are vague. Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), former Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D-Texas) and former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro all said they support the “idea” or “concept” of a Green New Deal.

The resolution may draw clearer battle lines.

“I expect that we’re going to see a lot of people saying they approve of the spirit, they love the bill, they just question whether it could pass as legislation,” said R.L. Miller, president of the political action committee Climate Hawks Vote. “But it’s definitely a starting point.”

“This is how green socialists will govern. It will be thoughtful, it will be politically pragmatic, it will still be ambitious.”

- Greg Carlock, Data for Progress

The Green New Deal, originally coined in the mid-2000s as a term connoting a way to bridge the environmental and economic goals, re-emerged last year as Ocasio-Cortez and other left-wing Democrats ran on unabashedly progressive visions of curbing climate-changing emissions and eradicating poverty in the same stroke. In November, activists from the Sunrise Movement and Justice Democrats staged sit-in protests in Democratic leaders’ offices, demanding they make a Green New Deal a policy priority in the newly flipped House.

Ocasio-Cortez joined the protests, and soon after unveiled a resolution calling for a select committee on a Green New Deal in the House. Pelosi rejected the plan even as roughly 40 Democrats agreed to support the resolution. Instead, she revived a decade-old select committee on climate change, and put a backbench moderate Democrat in charge of the panel.

But the demonstrations thrust the Green New Deal into the national spotlight. It proved popular. In December, 81 percent of registered voters said they supported a plan to generate 100 percent of the nation’s electricity from clean sources within the next 10 years, upgrade the U.S. power grid, invest in energy efficiency and renewable technology, and provide training for jobs in the new, green economy, according to a poll by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University. That included 92 percent of Democrats and 64 percent of Republicans, with an eyebrow-raising 57 percent of conservative Republicans in agreement.

Another poll published last week found voters narrowly supported raising taxes to fund a Green New Deal.

“The left is putting its heads together on how we can actually govern, how we can go from an opposition force, a resistance force, to one that can do things of the many, rather than the 1 percent,” said Julian Brave NoiseCat, a policy analyst at 350.org. Speaking of the resolution, he said, “There’s a lot in this.”

Stephen O’Hanlon, a Sunrise Movement spokesman, downplayed the disparities between the resolution and some of the initial demands his fellow activists made ― namely the lack of an explicit fossil fuel phase-out or a hard 2030 deadline for 100 percent renewables.

“It’s not a bill, which means there’s a lot of details to be worked out,” he said. “We still feel very good about the pieces that are still being figured out.”

The resolution includes justice provisions that would be difficult to criticize. It echoes the 2015 Dakota Access pipeline protests that Ocasio-Cortez credits with inspiring her to run for office. In one section, it calls for “obtaining free, prior and informed consent for Indigenous peoples for all decisions that impact them and their traditional territories.” The document opens with a pledge to “promote justice and equity by stopping current, prevent future, and repairing historic oppression of indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, deindustrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth.”

Ocasio-Cortez said at the press conference that her focus was on “fully funding coal miners’ pensions” and “cleaning the water in West Virginia.”

Yet the resolution looks beyond the Green New Deal’s impact at home. One provision, as HuffPost reported Tuesday, calls for the United States to “promoting the international exchange of technology, expertise, products, funding, and services with the aim of making the United States the international leader on climate action, and to help other countries achieve a Green New Deal.”

That could spark a new debate over how central climate change should be to the progressive foreign policy vision taking shaping ahead of the 2020 election. Though China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide over a decade ago, Americans boast far larger CO2 footprints per capita and remain the world’s largest historic emitters.

“We’re beginning to have a discussion about the debt we owe to the international community for our reckless treatment of the environment,” said Sean McElwee, the co-founder of Data for Progress. “It will be a tough discussion but it shows the way Ocasio-Cortez is changing the discussion.”

This story was updated with details from a press conference on Thursday.