A hundred years ago, in February 1913, some 87,000 art lovers viewed the International Exhibition of Modern Art, sponsored by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors at the Lexington Avenue Armory at 25th Street. There, they saw over 1400 works -- paintings, sculpture and prints -- divided fairly evenly between European and American artists.

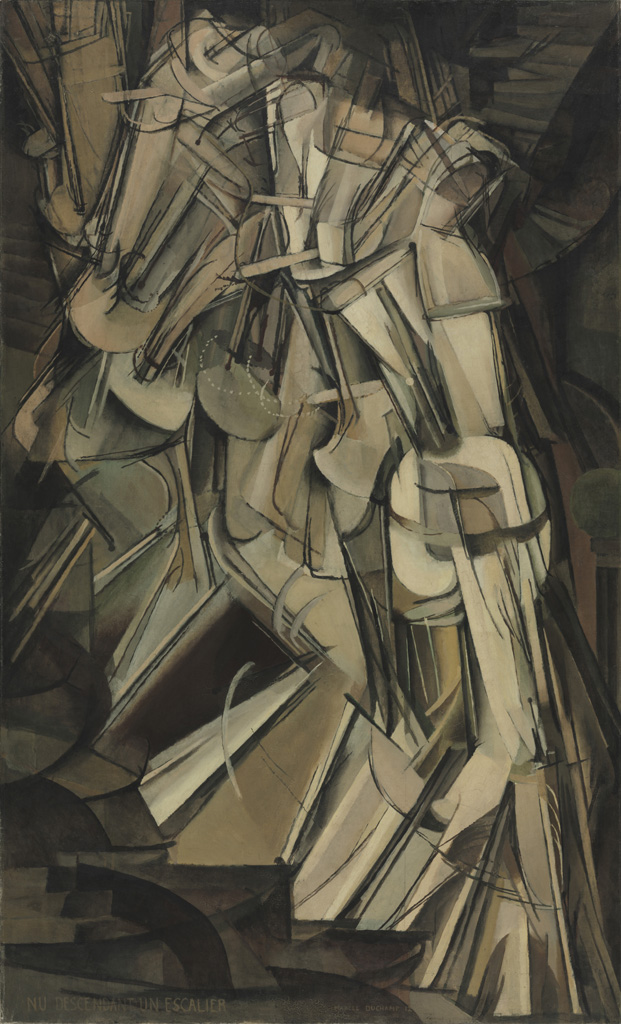

For many, the show -- especially the European work -- was shocking, even appalling, challenging their aesthetic sensibilities. When the exhibit traveled to Chicago, students at the Art Institute there held a mock trial and burned four of Matisse's paintings in effigy, disturbed by his unorthodox sense of color. Still other viewers, who saw the exhibit in New York, Boston and Chicago, were stunned by Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), perceiving it as a disturbing distortion of the human body.

But, says Marilyn Kushner, co-curator with Kim Orcutt, of The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution, opening October 11th at the New-York Historical Society, "The 1913 exhibit was not a mushroom that grew out of nothing." To prove this point, the NYHS Armory Show includes 15 works that were not seen in the original show -- works from National Academy of Design exhibits or from other contemporary galleries -- in addition to 100 works from the original exhibit, chosen to reflect the same ratio (European to American and sculpture to painting to print) as those in the Armory Show.

"Keep in mind," Kushner said, "that in 1913 only really wealthy people went to Europe to see contemporary art." With the exclusion of Alfred Stieglitz's 291 Gallery in NYC, a fourth-floor walk-up that was not "super welcoming," and a few other smaller galleries, there were not many places to see contemporary art in New York. "We were determined to show people what the public actually saw then."

What people were used to seeing in 1913 was a traditional mix. It was a moment when J.P. Morgan was amassing his enormous collection of medieval manuscripts, Sigmund Freud was collecting bronze Egyptian statuettes and art enthusiasts were in love with Netherlandist portraits and Rembrandt etchings, especially black and white designs and mezzotints. Examples of all three are included in a side room (with different wall color) at the NYHS which focuses on traditional works leading up to 1913 but also includes art created after the Armory Show exhibit.

Work done after 1913 includes a spectacular cubist painting by Arthur B. Davies and Aspiration, Winfield, (1911-1917), a painting by Oscar Bluemner who had several works in the original exhibit. Evidently, Bluemner repainted canvases that were in the 1913 show, scraping them down. So while the canvas for this work was in the original show, the painting was not. "The idea for the side room, Kushner said, was to let people digest the armory exhibit, then shock them back and then move them forward. It is very much like the original armory experience."

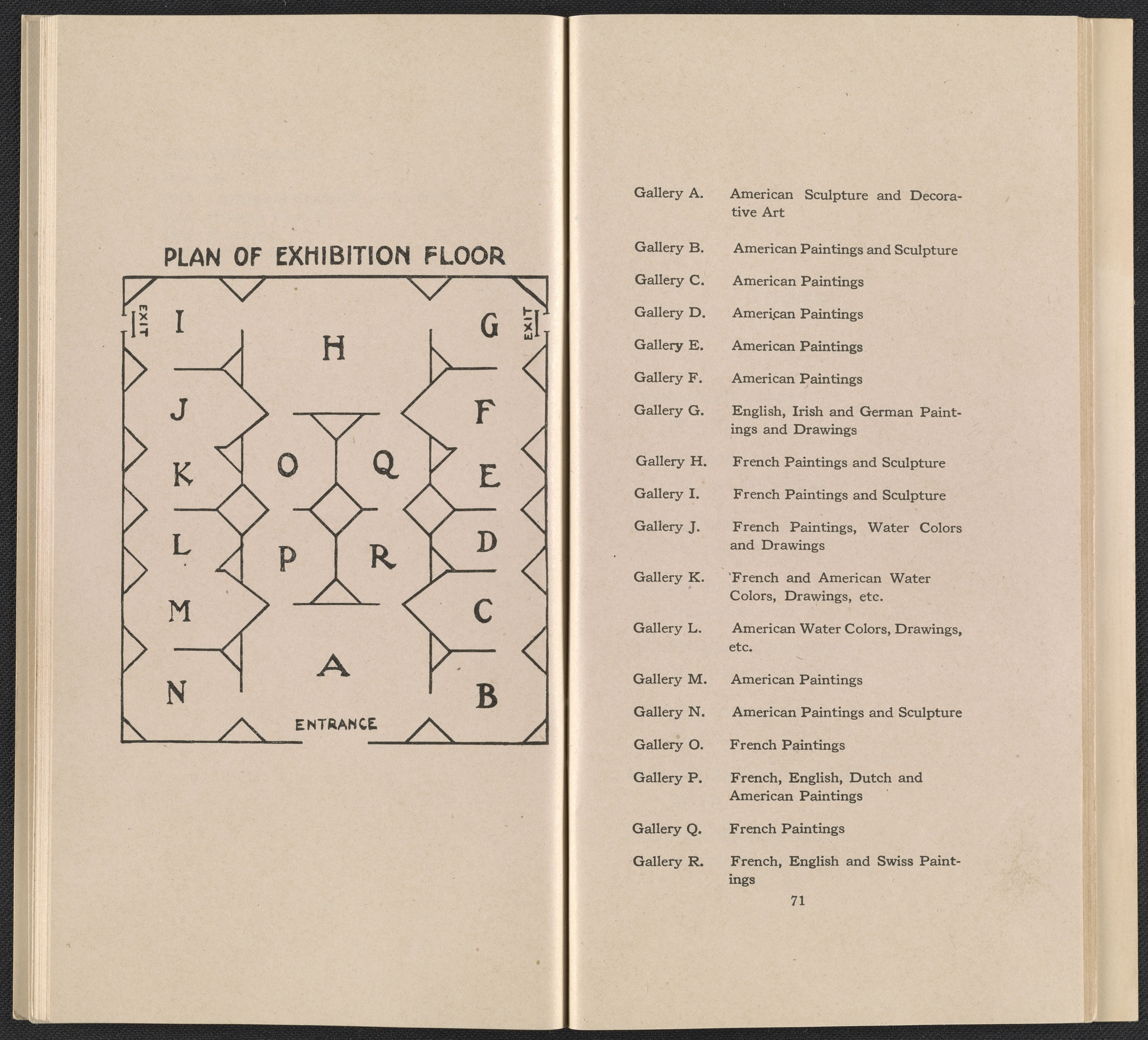

Unable to install the new show in the Lexington Armory, a cavernous, 55,000 square-foot drill hall which still functions as a military facility and one which has no climate control, making art insurance impossible, decisions were made to echo some of the elements of the original 18 gallery exhibit (a map of the original exhibit is included in the new show) in the much smaller NYHS space with its enormously high ceilings.

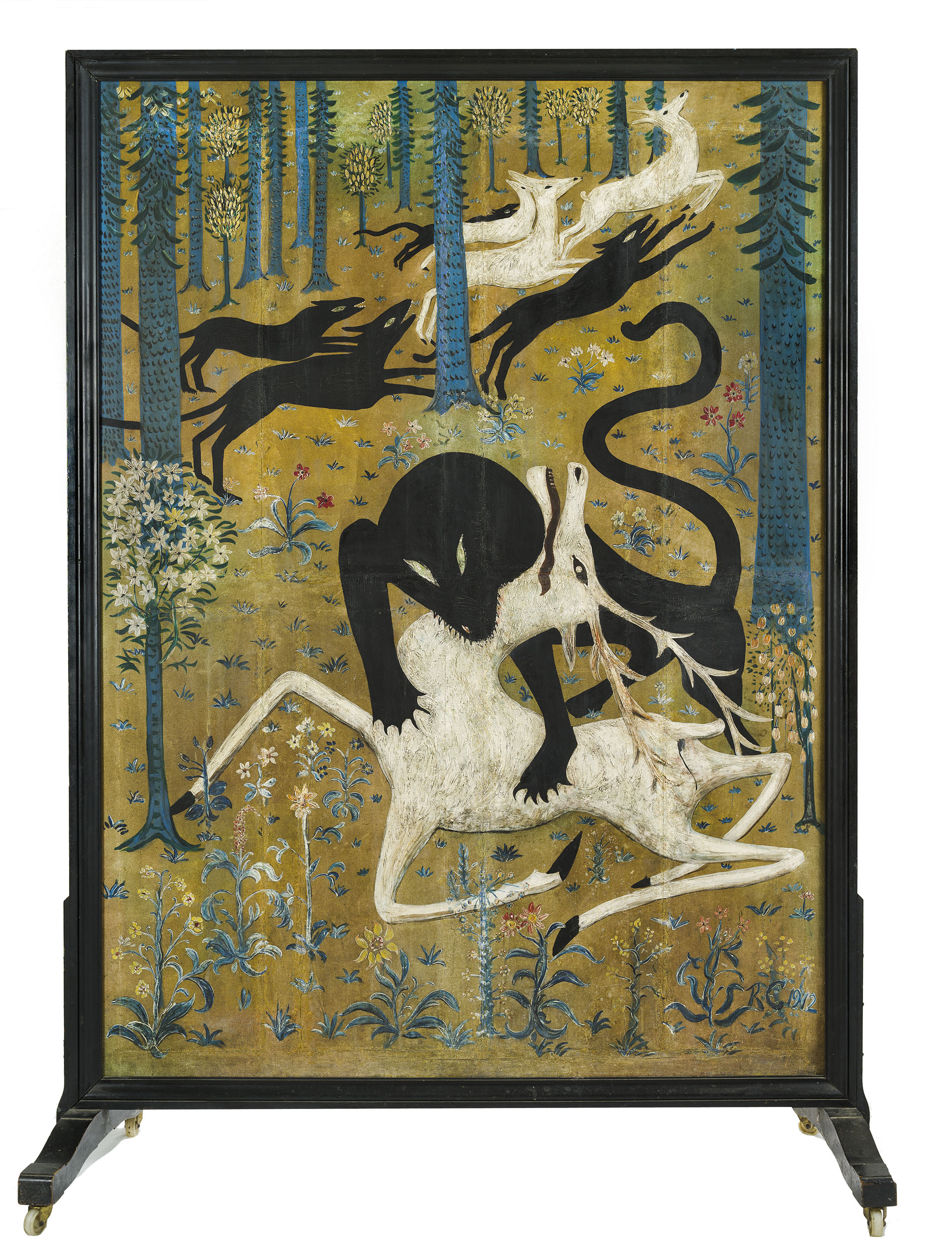

In 1913, people entered the exhibit in Gallery A, a space that featured American work. "We followed that design, having our viewers see the American art before the European," Kushner said, "although we put all of the American pieces together." The NYHS opens with Leopard and Deer (1912), a painted screen by Robert Chanler, a very popular artist in 1913 whose East Nineteenth Street townhouse was a social center for New York's art community. Chanler spent five years creating the work in Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's (his patron) studio in the original Whitney Museum of American Art on West Eighth Street in New York City, now the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture.

The idea was to show pieces that were important at the time, such as John Sloan's iconic painting, McSorley's Bar (1912), but also to reflect the original organizers' attempt to give a history of modern art from the 19th century to avant-garde pieces which led up to the 1913 Armory Show. The inclusion of works by Eugene Delacroix and James McNeill Whistler give a contemporary audience a sense of that history.

To the 1913 organizers' disappointment, many of the sculptural pieces in the original exhibit had to be plaster casts since it was too expensive to ship and insure bronze and marble pieces. "Ironically, we wanted the plaster casts," Kushner said, to reflect the original exhibit, but since plaster casts were fragile, "we only ended up with a few. Most of the sculptural pieces in our exhibit are bronze and marble."

If one considered work that was sold in the 1913 exhibit, 130 out of 274 pieces sold were prints, only two of them by Americans. Of the 128 European prints, some 100 were color lithographs, many sent over by Paris art dealer Ambroise Vollard in January, 1913, too late to be included in the New York show catalog. "People went crazy over them," said Kushner who was trained as a print curator, "because there was little color lithography here." Most of the prints sold for under $100, approximately $2400 today.

The NYHS society exhibit includes contextual materials drawn from the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution, many the same as those included in last February's The New Spirit: American Art in The Armory Show, 1913 at the Montclair Art Museum. There is a whole little room of examples including Davies original conception of the show, one that was completely different from the final plan, and a postcard of Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), that was actually mailed from a visitor to his wife.

After the 1913 exhibit, many of the original members of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors resigned, because, despite President Arthur B. Davies' defense of treasurer Elmer MacRae, they believed that money had been misappropriated. "We had our accountant look over MacRae's books," Kushner said, "and her response was that Davies was right and that MacRae kept pretty good records for an artist."

In keeping with the mission of the NYHS, the curators created an entire section depicting New York in 1913, to be entered before the armory exhibit. With the professional advice of Professor Casey Blake at Columbia University, who specializes in modern U.S. intellectual and cultural history and American studies, the NYHS tried to recreate the zeitgeist of NY at the time. "It was an amazing place," Kushner said, "almost like the 1960s. It was time when Greenwich Village became a bohemian place, when women were marching in the streets for birth control and when laborers were marching for their rights."

"The dance in place was the waltz but all of sudden it was replaced by the tango, the fox trot, and the bear hug," Kushner said:

It was the time of the Woolworth building, Coney Island and new forms of communication -- cables and telegrams. The epitome of all of this can be summed up in one little story. When President William Howard Taft was inaugurated in 1909, he rode in a horse and buggy. When Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated in 1913, he rode in a car.

NYHS President and CEO Louise Mirrer is particularly proud of the exhibit:

"The Armory Show at 100 once again exemplifies a key, New-York Historical Society differentiating strategy: to present great art as a means of engaging visitors in the enjoyment of learning about history, and to convey the history connected with the art so as to enhance and increase its appreciation and understanding.

"The Armory Show at 100 bridges the gap that traditionally separates art and history museums," she said. "It is a rare and wonderful opportunity to view many of the iconic works that delivered the full impact of modernism when the Armory Show first opened in New York 100 years ago while offering the chance to look back and understand why the original exhibition was such a pivot point, why it changed the way Americans saw and thought, and why nothing was the same afterward. The exhibition goes to the heart of New-York Historical's mission of Making History Matter."

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No.2), 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection

Henri Matisse, Blue Nude, 1907, The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection

Oscar Bluemner, Aspiration, Winfield, 1911-1917, Private Collection: Courtesy of Barbara Mathes Gallery, New York

Robert W. Chanler, Leopard and Deer, 1912, Rokeby Collection

John Sloan, McSorley's Bar, 1912, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase

Overhead view of Armory installation, 1913. Walt Kuhn, Kuhn family papers and Armory Show records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

The exhibition floor plan in the International Exhibition of Modern Art catalog, 1913. Walt Kuhn, Kuhn family papers and Armory Show records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Resources:

NYHS website: armory.nyhistory.org

The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution

Accompanying the NYHS exhibit is a book (not a catalog) with a different title: The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution which includes a full 1913 Armory Show checklist and a detailed bibliography.

Of Art and History

The Armory Show at 100:

Modern Art and Revolution

The New-York Historical Society

October 11, 2013-February 23, 2014