For as long as the young seminarian could remember, God had been a part of his life. He'd grown up in Anglican schools, then studied theology at Cambridge in preparation for the priesthood. And his love for his Lord only fueled his passion for the natural sciences -- at the university he marched eagerly into debates against atheists, arguing the case for intelligent design.

It came as no surprise, then, that Charles Darwin returned from his tour of the South Atlantic with case-fuls of specimens hinting at -- as he put it -- ancient "centres of creation" from which related species had spread and multiplied according to God's will.

But although he kept up his defense of creationism, something had subtly shifted in Darwin's mind on that voyage -- a change whose effects would splinter his most cherished beliefs, and would only be traced back to their source in the last years of his life. In a word, Darwin learned to doubt. Under the weight of new evidence, he lost his ability to trust that the Bible was literally true, that species were fixed for all time, that all laws of nature must be ultimately benevolent. Though he continued to work with his local church -- and resisted the label of "atheist" to the end of his life -- Darwin would never regain the inflexibility of his old theological opinions.

Of course, this one man's change of heart turned out to be quite helpful to modern science. Thanks to the theory of natural selection that Darwin helped develop, we now understand not only how new species evolve but -- in many ways -- how our own minds evolve.

For instance, consider a new study from the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which used our understanding of brain chemistry -- and evolution -- to map out how we update our beliefs and goals.

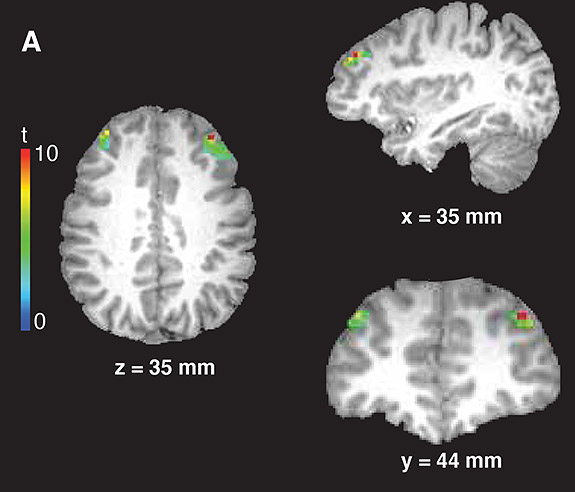

A research team led by professor Jonathan Cohen started by teaching participants a simple game: Press button "A" or "B" depending on which series of letters is flashed on a screen. As the subjects played the game inside an fMRI scanner, the researchers paid careful attention to a region of their brains called the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which we know is crucial to abilities like maintaining a sense of the current moment, switching our attention among different tasks and updating our goals when we learn new information.

Cohen's team found that the PFC works closely with an ancient structure known as the midbrain, which helps route and relay incoming information. When you learn something new -- a sequence of letters, for example -- the midbrain sends squirts of the chemical dopamine to your PFC, effectively tagging the new information as "for your immediate attention."

This close linkage between ancient and advanced brain regions reminds us of something humbling: Even our most elegant intellectual pursuits are rooted in the same basic chemistry that kept our distant reptilian ancestors fit and fighting. As complex as our cognition has grown, messages like "maybe neuroscience is cooler than I expected" and "this website could be important for my career" are founded on the same communication systems that taught our ancestors which mates to impress, which territories to defend -- and which beliefs to test and refute.

Darwin didn't live to see us probe the neural workings of our own decision making, but he did help usher in a crucial change in scientists' way of viewing the universe: Instead of seeing change as an aberration, we now expect it as the norm. And that in itself has been a change worth fighting for.