Prologue

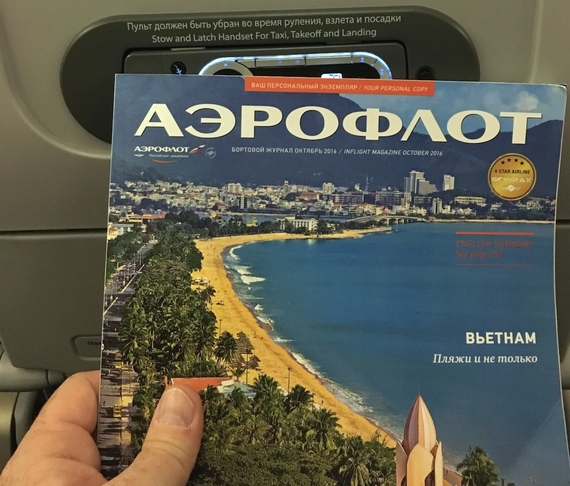

I received an email from a connection in the art world, putting me in touch with the organization of an artist in Brussels. His staff was assembling a group of journalists to write about his gigantic solo show opening at the State Hermitage Museum, in Saint Petersburg. They wondered whether I might be interested in flying to Russia to see the show.

This account draws on a knowledge of its subject matter so partial as to make the entire text extremely untrustworthy. And yet its subject is art, and a thing I have noticed after many years of making art and thinking about art is that nobody really knows anything about it. Many people are respected as authorities on the subject, but most of these authorities have simply asserted their claims long and loud enough that the crowd eventually shrugged its shoulders and went along. So I don't see why I shouldn't make my claim as well.

This is the first of several articles on the subject. I found I had a lot to say.

Genius Factory

When I was little, a rabbi explained his idea of genius to me: it is that quality of mind wherein the genius carries in his head an entire universe. This internal universe is active, and works in such detail as to have useful things to say about the external universe. The rabbi cited Einstein's thought experiments through which he worked out the principles of general relativity.

This rabbi's idea is closely linked to a concept which I think I have from Borges, although I can't find it now, and am beginning to suspect it comes from somebody else. It is that a successful genius is somebody whose magnificent internal universe intersects sufficiently with the universe all people understand that it can merge with it, and change its course. The unsuccessful genius appears too early, or too late, and the intersection is not broad enough to allow a merging of the two universes.

It is no secret that the art world is worshipful of a quantity it calls genius, and seeks people in whom this quality inheres, in order to extract their product and shower them with praise and rewards. This bias seems to me most pronounced in the strange trans-national sector, where a rolling party of fairs, biennials, and state and museum events occupies an elite community of artists and clientele. The quality of genius most in demand is not that the artist should have a magnificent internal universe, nor that that universe should be capable of changing our own, but that the region of intersection between the two should be narrow and tenuous. The peephole through which we viewers gaze into the artist's internal universe should be dim and filmy, rendering that alien universe mysterious and numinous. The art must be heavy with portent and implication; it must have a blank and startling quality. To fill the vast exhibition spaces of the trans-national scene, this art is going to have to be quite large, larger than any one set of hands can manufacture, and at this suprahuman scale, it must be able to stake its assertions of merit without immediately prompting laughter. Therefore it must be rich in the quality of genius.

These formal demands have turned the entire art world, and the trans-national scene in particular, into a genius factory. The proving method used to gain entry into this factory was outlined by André Breton in 1924:

Recently I suggested that as far as is feasible one should manufacture some of the articles one meets only in dreams, articles which are as hard to justify on the ground of utility as on that of pleasure. Thus the other night during sleep, I found myself at an open-air market in the neighbourhood of Saint-Malo and came upon a rather unusual book. Its back consisted of a wooden gnome whose white Assyrian beard reached to his feet. Although the statuette was of a normal thickness, there was no difficulty in turning the book's pages of thick black wool. I hastened to buy it, and when I woke up I was sorry not to find it beside me. It would be comparatively easy to manufacture it. I want to have a few articles of the same kind made, as their effect would be distinctly puzzling and disturbing.

- p. 105, A Book of Surrealist Games, Brotchie/Gooding

The artist with the audacity to create a Breton dream-object, and the talent to do it well enough, may be accepted into the trans-national sector, where a wealthy funding community covers the tremendous expenses of industrial-scale art studios. Once an artist has gained entry into this circuit, he faces a second challenge, which undoes most of the few survivors of the first round of selection: that of over-resourcing.

Some years ago, I read a compilation of responses from famous movie directors to the question, "What would you do with an unlimited production budget?" There were many movie proposals, but only two answers of fundamental interest:

1. "I could not work under such conditions."

2. "I would make a movie called The Yellow River, which would be physically as long as the Yellow River." [to clarify, the Yellow River is 3,395 miles long, and the director was referring to 35 mm film, which has a length of about 1.02 miles per hour of playing time]

The first answer is the barrier which undoes many artists who have gotten through the door. They cannot make work with the resources provided and the scale demanded. They undergo explosive decompression. These are the flashes in the pan who get a ton of press for a season or two, and five years later, nobody has ever heard of them.

The second answer is the kind of answer the genius factory demands. There is something bracing and uncanny about it. It is overwhelmingly large, and makes a simple and enigmatic identification of linked but different entities: it is a map as large as its territory. This answer is an answer of genius.

As far as style goes, there are three key elements to this rarified kind of art. The first is that it should be conceptual. The second is that it should be surreal. And the third is that it should be industrial. Many hands may labor to make each object, but each object should provide false evidence that it comes from a world where these objects are common, and even machine-made. They are like those upsettingly heavy metal cones from Borges's Tlön, fragments of imaginary worlds gradually undermining the real one.

An Invitation to Saint Petersburg

The trans-nationals have the resources to pluck a writer from New York, transport him to Saint Petersburg for one day, and then whirl him back. Clearly, though, it would be terribly ungracious to accept such a junket and then write a bad review. For my part, the proposal was very appealing, but I was not about to sell my soul for it. I won't write well of something I don't like. I had not previously had contact with this elusive sector, and did not know the art or thought of the artist in question, Jan Fabre. He is a Belgian, born in 1958, the first living artist to have a solo show at the Louvre, which led to his invitation to install the much larger show at the Hermitage which I was under consideration to go see.

So I looked up Mr. Fabre to see if I was open to his work. To my ear, my description of his sector sounds a little cynical. But all circumstances in this world of scarcity are merely tools, and tools are largely neutral. Good artists make use of whatever they can lay hands on, and good art is everywhere.

A sculpture from 1998 aptly sums up why I ultimately decided in favor:

This is something I can speak to, and which speaks to me. It has an ontological surrealism which is very sympathetic with my way of thinking. Wistful and bittersweet, it is a monument to the human need to quantify and to understand, even when such efforts are inapplicable - when the scales of reference are incommensurate, when the measurement is useless, when the thing to be measured is so ephemeral that it can scarcely be defined. This is a monument to this yearning, to the melancholy of its failure, the joy of its attempt. As Fabre chooses to photograph his sculpture here, Man is tiny, as indeed he is, but his gesture is profound. His gesture - his reason - and not his stature, makes him the measure of all things. There is a region of intersection between Fabre's universe and my own.

I accepted the invitation and flew to Russia.

To be continued.