Finally we conclude a series of thoughts and observations on Jan Fabre's art, continuing from here, here, and here. He currently has a gigantic exhibition, Knight of Despair/Warrior of Beauty, installed at the State Hermitage Museum, in Saint Petersburg, Russia. I had the pleasure of seeing it there, and have spent a long time since then reflecting on my understanding of his work.

As we have discussed, Fabre is a magician, a much more feasible occupation in the mysterious nighttime of art than in the cold daylight of the real world. He develops a loose conceptual framework for his projects, and then moves inside this framework on the basis of inspiration. Because he trusts in his sense of play, of the work presenting itself to him, he falls on the opportunist side of the opportunist/perfectionist divide. This is a divide I first heard of in the context of evolution: that evolution is an opportunist. It doesn't sit around all day designing an ideally-adapted organism, as a perfectionist would. Instead, it tries everything it can, and if something works, great. Both strategies yield benefits, and have their representatives in the arts. Vermeer and Kubrick, for instance, are perfectionists. They make few works, but the works they make are astonishing and divinely crafted. Picasso and Werner Herzog are opportunists. They make a lot of work, and a lot of it fails, but that is inherent to the procedure, and when they succeed - greatness. Fabre is in this latter camp, which boils over with invention and mayhem.

So we will discuss here a few pieces which, for me, work. They are the reward for his searching and his frenetic generation of images and objects.

APPEARANCE AND DISAPPEARANCE

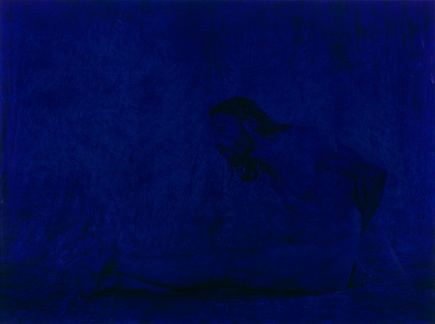

Jan Fabre, The Appearance and Disappearance of Christ I, 2016, 124 х 165.3 см

Ballpoint (bic) on Poly G-film (Bonjet High Gloss white film 200gr), dibond

This is a series consisting of enormous black and white photographic prints, of vaguely baroque imagery, which appear to have vanished behind gleaming cobalt surfaces. A closer inspection reveals that these otherworldly jewels are created in the most tedious way from the most prosaic materials - layer after layer of lines drawn with blue ballpoint pen, Bic perhaps, at 69 cents a pop, until a dense and dazzling mat of ink is developed. Through this mat, it is nearly impossible to see the submerged image. And yet it presents itself in certain light, at certain angles of the eye. And most uncannily, it is quite clear to an iPhone.

This is not what the pieces look like at all - they can scarcely be deciphered in person. In this series, a private moment of doodling in a magazine is blown up to a statement of ontological significance. The title catches it, appearance and disappearance: these objects hover between the being and non-being of the image, presenting all the possibility and menace of an indeterminate degree of existence.

FALSIFICATION DE LA FÊTE SECRÈTE

Left: Melchior de Hondecoeter, Dead Game, before 1783

Right: a nearby drawing by Jan Fabre

(not photographed at the same scale)

These drawings are installed irregularly in a hall with the Flemish and Dutch paintings which inspired them. They are small drawings, with the bright colors and quirky humor of children's books of the 19th century. In contrast with the industrial-scale martialling of forces required to execute so much of Fabre's work, they are appealingly simple and direct. The strengths and weaknesses of Fabre's hand show through here. The work is imperfect, and its varying qualities reflect the character of a living man. To other artists, I think, Fabre is at his most recognizable here, his most vulnerable. He becomes like all of us, a pilgrim to the great works of the past, trying to recreate what he loves in those works, and in his failing, as all of us fail, discovering his own distinct nature. Fabre's drawings here recapitulate the artist's journey toward maturity, demonstrating the adorations of the art student and the solitary creativity of the artist.

ALIENS

(my title, not his)

Finally we come to the installation which, for me, is the masterpiece of the exhibition. It is the best of the rewards for Fabre's opportunistic method, the point at which the elements align and his magical vision becomes embodied in matter. The room in which it is installed holds gigantic still lives and animal scenes by 17th century Flemish master Jacob Jordaens. In these paintings, we see the world through an eye attentive to the strange. The masses of animal and vegetable matter come very close to being truly alien - right here in the heart of the Western tradition, the most familiar tradition, the alien is lurking. These paintings, taken together, gaze so closely at the real world that it reveals its persistent weirdness. And right here, Fabre introduces his bizarre menagerie of the bones of men, covered over in beetle shells and fused with mounted birds. The men have twisted postures and surprising colors, and the birds are incongruous, but taken altogether, these creatures have biological integrity. They make sense relative to themselves; they simply happen to be from another world.

Fabre places them in a room where our own world becomes as unrecognizable as it gets. Two passages of the nearly foreign therefore appear in one place, and for a glimmering moment, the viewer may slip over into Fabre's universe. His iridescent men may be the native creatures of our world, and our own squids and sharks, lions and leopards, cantaloupes and cabbages become the disconcerting intrusions from elsewhere. Fabre's insight is that the paintings of Jordaens are so peculiar as to alienate us from our world, and thus, make us receptive to another world as our own. He fashions, to the extent art can, a gateway between worlds.

This is the most potent instance of his magic which I saw in the show.

---

Jan Fabre: Knight of Despair/Warrior of Beauty, State Hermitage Museum, until 4/30/2017