As the only woman under 65 -- and not wearing a hijab -- I wondered if I'd found the right place. Just 15 minutes before, I'd hopped in a taxi in my pajamas -- I forgot to set my alarm -- and zoomed past army tanks and yellow Hezbollah flags.

"I'm here for acupuncture," I said to the woman dressed in black behind the desk.

"Yes, please take a seat, the doctor will see you in a few," she replied.

As I surveyed the room, a quiet woman in a navy blue hijab offered me some Arabic coffee. My pajamas and emerald Ottoman slippers weren't the only sign I was strange -- I was also the only woman who put sugar in my cup.

"I never put sugar in my coffee -- I hate it," one of the older women said, before grabbing her lower back and groaning.

When most people think of acupuncture and Chinese medicine, they don't think of the Middle East -- or Islam. I didn't either, until I moved to Beirut and asked a colleague where I could find an acupuncturist -- expecting to find none.

"Why, right here in our very own hospital," she said, telling me about a young Lebanese doctor who had recently studied acupuncture in China.

"But how much does it cost?" I said, expecting the price to be out of range (like in New York).

"It's free, I think -- at most, just a co-pay," she said.

Naturally, I called immediately to schedule a number of appointments with a doctor who turned out to be just as talented at placing pins, as she was lovely as a person (just like her hot pink hijab). But the reduced hours and travels of summer forced me recently to find someone new.

"How are you feeling -- is the treatment working?" the women in the waiting room began asking each other, sharing their aches and complaints aloud -- unlike back home, where no one in the waiting room dares utter a sound.

As a number of tan women in sleeveless sundresses strolled through the door and exchanged kisses on the cheeks, our waiting room was quickly becoming as full of laughter and gossip as I imagined a beauty parlor in the south might be.

"Please, Emily, have some zataar," the acupuncturist's assistant said, pointing to some pita brushed with sumac and sesame.

Any irrational anxiety I had about catching a stomach bug was soothed by the thought of ruining my acupuncture high with unnecessary hunger -- plus, it just looked so damn good.

When the acupuncturist, a male doctor with the lean frame and soft eyes of a yogi, sat down to write some notes, his assistant nudged me to tell him why I had come.

"Well, nothing's wrong, I'm just here because acupuncture worked miracles for me in the past, and I want to keep using it," I said, before detailing past diagnoses and discomforts.

"While I understand everything you're telling me from the perspective of western medicine -- you still haven't told me your chief complaint -- from inside of yourself," he said, challenging me to articulate my own embodied experience.

Since I wasn't used to sharing in a crowded waiting room, I had nothing to say -- or maybe I just hadn't given it much thought.

"From the model of Chinese medicine, your main problem, you know, is your breathing," he said, drawing a detailed map of my meridians on the desk to illustrate my whole system.

"How do all of these people find out about you -- and acupuncture -- in Beirut?" I asked.

"Some, like you, already know about acupuncture, and they seek me out -- others hear about me and the positive results of acupuncture from their friends," he said. He's now forced to turn many patients away, because his schedule has become so full.

"I will treat you today, but starting next week I won't be in my office -- I'll only be working in my clinic in the refugee camp -- for Ramadan," he said.

"So can I see you there?" I asked.

"Sure -- but do you even know where it is?" he said, surprised by my request.

"Yes -- I helped teach yoga there -- to the refugees," I said, as we began comparing notes about our experiences in the camp.

In his clinic, he provides acupuncture to refugees of all ages -- for all kinds of problems -- for free. Not surprisingly, many of them come seeking treatment for depression.

"But do they call it depression, or something else?" I said.

"Well, from the Chinese point of view, depression cannot be separated out as something separate -- we must think of the whole -- but yes, some call it depression -- while others just grab their neck, and say that their collar is choking them," he said.

As he ushered me into the treatment room, he instructed me keep on all my clothes. The pins he placed didn't go where they normally did. One even went right on my throat -- and I could barely swallow.

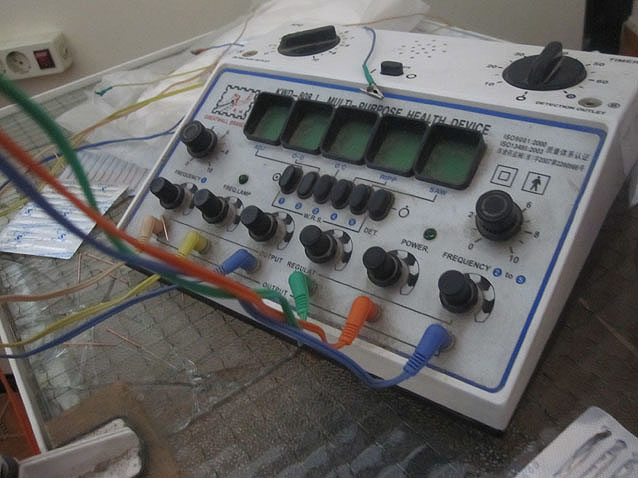

"Don't worry -- this configuration will help you breathe more deeply -- now try taking a breath," he said, as he hooked up the needles to the current of a machine nearby.

As air rushed rapidly and deeply into the deprived cavities of my lungs, I wondered if I had inhaled all the oxygen in the clinic. No wonder the women in the waiting room had grown so quiet.

"Much better, yes?" he said, before smiling and closing the curtain to leave me alone.

Suddenly, I no longer felt the needle in my neck. And instead of the woodwinds and synthesizers of New Age music, I was lulled to sleep by the hushed sounds of Levantine Arabic in the hall -- which, for a linguist, is even better.

"Emily, are you awake?" he said a half hour later, crawling under the curtain.

As he began to knead his fingers into parallel pressure points on my feet, I no longer winced -- like I had before he placed the pins.

"How old is your youngest patient in the refugee camp?" I asked.

Watching him scroll through his mental roladex of young refugees, I could feel their presence in the room -- along with all of the refugee children whom I had met as well.

"Five years old," he said, slapping me affectionately on the shoulder like a high school coach, and leaving me alone.

Staring at the ceiling and stuck with pins, I couldn't stop thinking how amazing it is that in Beirut, acupuncture is not just for the wealthy. And since acupuncture here isn't considered a status symbol or a bourgeois luxury -- it can be just medicine, which is what it should be. From refugees to millionaires -- and children to the elderly -- acupuncture in Lebanon is available to all -- for a relatively low fee (or even free).

"So, we'll be seeing you again?" the doctor said, when I returned to the waiting room to schedule my next appointment.

"Oh yes, you'll be seeing me again soon -- in the refugee camp," I said, imagining a Ramadan not of walking on pins and needles -- but, instead, of being soothed and healed by them.