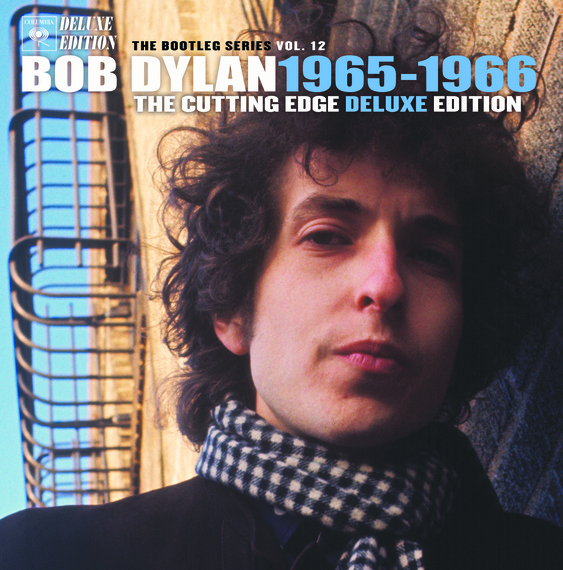

On November 6th, the latest installment of Bob Dylan's largely unreleased recordings in The Bootleg Series will be available, in several versions. The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12 (Sony Music Entertainment/Columbia Legacy) lets you hear the making and composition of the songs on three of Dylan's best-known, and also best-loved, records: Bringing It All Back Home (1965), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), and Blonde On Blonde (1966). Inside these three records are worlds of wonders. Now, you will be able to hear the evolution of those wonders - how Dylan, and the musicians with him, made it all come to pass.

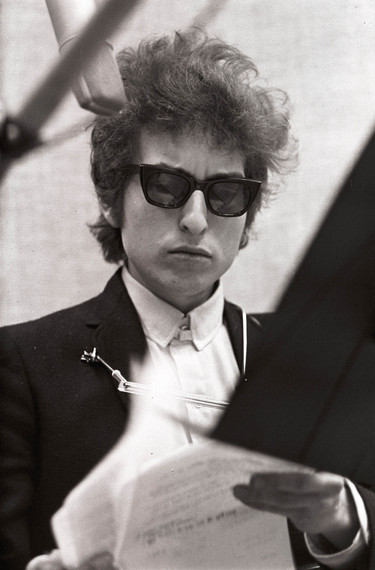

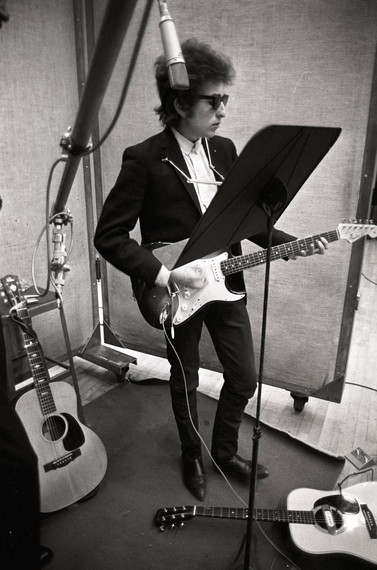

This is the Bob Dylan who became iconic. The albums' cover photographs are how very many people think of Dylan, still, today. He's lean, his hair in a snarly nimbus above a thin white face, with its keen, challenging eyes looking right through you. He is not listening to you; you're listening to him. On the cover of Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan is 23. On the cover of Blonde On Blonde and The Cutting Edge, he is 24 years old. Dylan had a style then that is still compulsively copied. But the clothes are just a part of it, and they hardly made the man. Those are but the trappings and the suits of show. Add to same the youth himself, and, ladies and gentlemen, you have a rock star.

Bringing It All Back Home (1965) bears the heavy mantle of being the Dylan-Goes-Electric album. It's always seemed an odd distinction for me, perhaps since I was born too late, to divide Dylan into acoustic and electric, folk and rock. His music is too multitudinous - and was, even way back then - to be pigeonholed into any categories. By March 1965 Dylan had clearly already gone electric, and this record is the pure proof, although his flashpoint performance of "Maggie's Farm" at Newport Folk Festival wouldn't be until that July.

What went into the making of the songs on this album? Buckle up, hang on, and let's go. Tom Wilson's gentle baritone leads us into the bounty, stating, "We got a good sound, here," and then giving way to what he slates as "Dime Store, Take One." Just Dylan's voice and the guitar begin: "My love, she speaks like silence / Without ideals or violence...." and, then, you hear a companionable, thumpy bass line. "Valentines can't buy her," croons Dylan, and emphasizes it with a delicate, light harmonica. It's gorgeous, clean and clear. But it's not good enough for the 23-year-old singer-songwriter-musician. He stops after the books and quotations, and declares his intention to do it again. They do, and he and the 20-year-old John Sebastian (a Village folk and bluesman, with "Do You Believe In Magic?" and all his joyful Lovin' Spoonful hits yet to come, playing bass) nail it to the wall this time, the whole song, every long verse. If you think Dylan's done, though, and the song you know as "Love Minus Zero / No Limit" is in the can now, you're wrong. He goes on to sing it again, and again, and again - different every time, phrased differently, the tune shifting up and down, the lyrics changing, the musicians, the instruments and their roles coming and going. Drop in Bruce Langhorne on the guitar, Bobby Gregg on drums, the remarkable Paul Griffin on piano. Keep on keeping on. The cumulative effect engages, delights, overwhelms, and finally sends you head over heels. The range of treatment of each song is surprising; the force of Dylan's creative drive, and spontaneity, have never been more clearly heard. Draft after draft, version upon version, of songs roll down on you like waters. Welcome to The Cutting Edge.

Hijinks abound, to give you a little catharsis as you listen, and capturing the energy and personality of these sessions. Wilson slates "Alcatraz to the Ninth Power." "No, that's not the name of it!" Dylan shouts. "That's what you told me when you left," Wilson insists. Bob insists right back: it's "Bank Account Blues." And the slowly flowing, slightly tinny tune rolls - we know it as "I'll Keep It With Mine." Go ahead, Dylan, rhyme odd and not. Sing through your nose in a key too high to achieve, on the first go. It's working anyway, right from the start. "That's nutty, man," says Wilson in the end - but he says it admiringly.

"I was ridin' on the Mayflower when I thought I spied some land," Dylan yowls, and then he and Wilson dissolve into giggles (Bob) and chuckles (Tom). Take two goes all the way, with a vision of the settling of America that feels crafted by Herman Melville and Nathanael West on a weekend bat. That's Bob Dylan's 115th dream, people.

So many of the songs are slower at first attempt, and then rise in tempo. "She Belongs To Me" is not a swift-paced song, as we know it from the final version on Bringing It All Back Home - but, here, it's almost a dirge. Dylan's voice doesn't rise and fall as it does later on the song, and the soft trio of guitar chords, and occasional harmonica touch, do little to brighten the sorrow. "Salute her on Sunday, bow down when her birthday comes," Dylan tries first, in a solo acoustic version of immense beauty. Then he speeds up the song, like a heartbeat increasing. On the next take, Wilson identifies the song as "My Girl." Hey, Temptations - Dylan will see you, and raise you. Faster still. He's got it the way he wants it, now.

The opening track of Bringing It All Back Home, "Subterranean Homesick Blues," is amidst the sessions as a strum-chant, the tune most definitely an afterthought once the words have come. Dylan sings the same note on almost every single syllable, paying attention not to the tune but to the words. The words are what matter, the rapped-out patter of progression he will call "Subterranean Homesick Blues." He has real fun with the harmonica here, until he smashes to an abrupt end, and brings in a host of instruments to join in.

"Mr. Tambourine Man" has a ragged start, with Dylan and Wilson going back and forth about when to begin. Dylan sings it alone, with the instruments tagging along, keeping time. A telephone rings. They begin again, but Dylan stops in mid-refrain: "Naw, I can't...hey, the drummin's driving me mad, I'm goin' outta my brain."

Bringing It All Back Home would have been enough for the year for most musicians. Dylan, instead, embarked upon a tour of England in spring 1965, from which he returned to record Highway 61 Revisited. His celebrated appearance at Newport fell between the two recording sessions for his second album of the year, which was made in the way Dylan had begun to record by then. Musicians would assemble in a room. Dylan would take and re-take, compose lyrics and alter melodies, while they waited, assisted, waited, improvised, re-took, recorded. If a record didn't sound right when it was finished, Dylan would assemble another, largely new, group of musicians, and have at it again - as he did during the Blonde On Blonde sessions in Nashville and the Blood on the Tracks sessions in Minnesota - working in the same intense manner until he was happy with the result.

It's a Sartrean way to record, and one that has brought out unsurpassed performances over the years by individual musicians like, here, Robbie Robertson, Kenneth Buttrey, Paul Griffin, Al Kooper, Mike Bloomfield, Rick Danko, Charlie McCoy, and Dylan himself. Some of the musicians, including Kooper, who provides an essay for The Cutting Edge, have spoken years later about what it was like to be there. Now we can hear at least some of it, flies on a long-lost wall.

The most takes survive from the June 15-16 sessions of two songs, "Like a Rolling Stone" and "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry." In March 1966, Dylan told Jules Siegel, writing for the Saturday Evening Post, about "Like A Rolling Stone." He said he "had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, 'How does it feel?' in a slow motion pace, in the utmost of slow motion following something. It was like swimming in lava....Seeing someone in the pain they were bound to meet up with. I wrote it. I didn't fail. It was straight." Fifty years later, "Like A Rolling Stone" remains Dylan's most popular song.

Part 2: From "Like A Rolling Stone" through Blonde On Blonde, coming soon.

Read my full review at No Depression here.

All photographs © and courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.