On the Future of Wagnerism, Part 8: Macon, Georgia, The Road Leads Back to You

Steve Mass, the Mudd Club, Wagner and Me

by Lawrence D. Mass

"O Wagner, westward bring thy heavenly art,

No trifler thou: Siegfried and Wotan be

Names for big ballads of the modern heart.

Thine ears hear deeper than thine eyes can see.

Voice of the monstrous mill, the shouting mart,

Not less of airy cloud and wave and tree,

Thou, thou, if even to thyself unknown,

Hast power to say the Time in terms of tone."

--Sidney Lanier, 1877

In the years before the High Line emerged as the new epicenter of New York City's high culture, my sister Ellen and I were browsing in one of the West 22nd Street art galleries that foretold of West Chelsea's transfiguration from the meatpacking district and late-night gay cruising scene. The gallery's featured artist was someone neither of us had heard of. Ellen, an environmentalist and artist whose progressive politics are more discernible in her probing photography of the ordinary and downtrodden than in her watercolor landscapes with their subtle pastels, was pleased by what she was seeing. What did I think? Yes, I agreed, the paintings were sensual and abstractly appealing. But I felt I had to know more about the artist and the subject and context of the art before I could render an opinion.

Dinner with Hilan Warshaw at Café Tallulah, a French bistro on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Warshaw is the creator of several music documentaries, including Wagner's Jews and Lyric Suite, a work-in-progress which tells the background story of Alban Berg's previously unknown affair with a Jewish woman and features a performance of the work with Renee Fleming and the Emerson String Quartet. Hilan and I are mostly on the same page about Wagner, frustrated at how difficult it is to get beyond the controversies that continue to waft within and around Wagner's works and their appreciation. Though we are in agreement against any kind of censorship in principle, Hilan wondered if he should expose his baby son to Wagner's music.

Aesthetics discourse has a long history. Every orientation has been articulated and labored over. The one reflected by me in reaction to my sister's question is not widely endorsed: that initial impressions of art cannot be trusted. People do not want to be told that their spontaneous reactions to music or paintings need vetting. And in truth, I accept and respect their viewpoint as one I myself otherwise might endorse. Because of how much pain love-at-first-sight/hearing intoxication with art eventually caused me, however, I have been aversively conditioned to approach art with a lot more caution. Because of the fallout for me personally of my love of Wagner, all art has become suspect, guilty until proven innocent, and my reactions to it henceforth must be cleared through security and sobriety checkpoints, like screening passengers at airports and museums for weapons, or testing for blood alcohol levels. Like someone who slowly realizes they were raped, abused or otherwise exploited and will henceforth meet all romantic overtures with guardedness, or Holocaust survivors who reflexively distrust, I am now reprogrammed to never again allow myself the freedom to fall head over heals in love with art.

_____

Richard Boch, a doorman at the Mudd Club, is completing a book about his experience there. He wanted to interview me about my brother, Steve Mass, who collaborated with several others in the creation of the club in 1977. With inchoate misgivings, I agreed to speak with Richard, with whom I was otherwise acquainted, but I withdrew when I sensed that this would not be the right venue for me to try to express myself about Steve and our estrangement.

_____

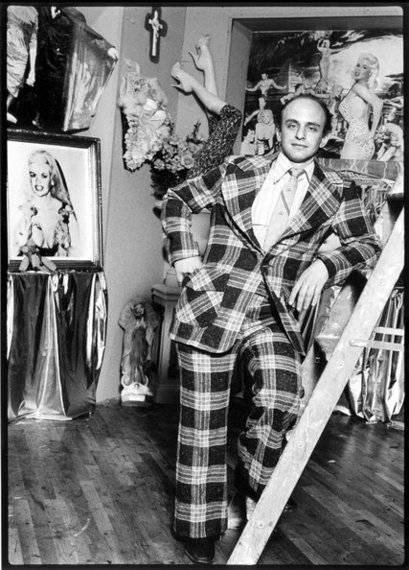

I look at the two best-known photographs of Steve, of him in a plaid suit and another with him looking like the proverbial mad scientist, leering out with one eye, like a gecko, as he looks with the other through a microscope like the one or perhaps the very one my father the pathologist had at home when we were growing up. The plaid suit appears to be a costume or fashion statement of some kind, the mad scientist a fantasied "Dr. Mudd." These are fictional personae, I think to myself, and their creator is someone I never really knew.

The reasons for that are so various and elusive that I've decided to embark on these reflections to help me do what writing is best at--recouping people, places, things and times from memory and history, in hopes of giving them context and perspective.

Plaids, in curtains, upholstery and clothes--like those of the Catholic school uniform skirts that became mandatory in America in the 1940's, and the madras plaid shirts favored by Steve's high school peers--were in style in the 1950's America where Steve came of age...

Steven Arnold Mass, nearly six years my senior, was born in Macon, Georgia, in 1940. Not an optimum time or place for Jews, to say nothing of gays. Steve wasn't gay but, unbeknownst to both of us during a time when even the word "homosexuality" was so taboo that it was virtually never uttered or even written, I was.

A German American family down the road had a sign in their driveway that read "No Dogs or Jews Allowed." Later, I learned that "No Dogs or [substitute any immigrant group] Allowed" was a not uncommon posting in the history of so-called melting-pot America. Though I knew we were Jewish, such was my disconnection with our Jewishness that I'd no idea this had anything to do with me, and so I would play there with the other boys, searching the abandoned and overgrown pool for turtles and snakes.

Likewise down the street was my best boyhood friend, Chester, whose American-Gothic lookalike mother ranted endlessly about "niggers," and who later decided to forbid Chester to play with me because I was a Jew, which made me cry. Chester's dad worked at a gas station. I think they were Klan members. The Klan was very active in our area. Crosses were burned and when we were children, it was said that a black man had been hanged in front of one of the downtown's 2 movie theaters.

This was the Southern heartland--with its pervasive mentality of bigotry and intolerance, of cruelty, meanness and hatred--that Tennessee Williams captured in his play Orpheus Descending. It's the South that never really surrendered to the North and that has been key to the rise of the present-day carpetbagger Donald Trump.

Such was the stigma we felt about being Jewish that we kids would walk on opposite sides of the streets of the town's two Jewish houses of worship, both of which our family belonged to--the orthodox synagogue ("Schul"), Temple Sherah Israel, where Steve was bar mitzvah'd, and the reformed temple, Beth Israel, where my sister was confirmed, and where we all got dressed up in costumes for the Jewish holiday Purim.

Just as Verdi's Nabucco captures key aspects of our conflicts in Iraq with startling prescience, so Purim likewise fortells of those with Iran. Haman, the King's confidante who attempts to foment genocide against the Jews, has his precise counterparts today in former prime minister Ahmedinejad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Meanwhile, Esther's ascendancy as Queen, and thus with the power to denounce Haman and influence the King favorably with regard to the Jews, has its admittedly troubled reincarnation in Ivanka Trump's marriage to an orthodox Jew.

I remember choosing to dress as King Ahashueras after my initial taboo choice of Queen Vashti who, in contrast to natural-beauty, plainly-dressed Esther, got to wear a lot of jewelry. Early gay longings entangled with Jewish lore and festivity.

Meanwhile, outside those confines of Temple and Schul, consciously or unconsciously, we kids would seize every opportunity to minimize our status as Jews. As mandated by our parents, we attended Friday Sabbath and holiday services, Sunday school and Hebrew school, but with the same enthusiasm we had for going to the dentist. I remember once seeing our rabbi crying, frustrated at the difficulty of successfully imparting what he felt we needed to know about being Jewish and Judaism. Sadness. Weakness. Not things we wanted to feel or be around.

However thick the ambient anti-Semitism, I don't recall any major incidents of anti-Semitic violence during the years of our upbringing, like the notorious Leo Frank lynching in Atlanta in 1913, and the crimes of racism that remained commonplace. And as it turns out, the South has deep Jewish roots, communities that went way back, preceding the Civil War. This was true of Macon and elsewhere in Georgia, especially Atlanta and Savannah, and in neighboring states, and it included some who figured prominently in the history and heritage of the South, like Confederacy treasurer Judah Benjamin and David Emmanuel, the first Jewish U.S. governor. The University of Georgia Law School is named after Harold Hirsch, a prominent Atlanta attorney. As during the French Revolution, Jews found themselves on both sides of the American Civil War and a principal scapegoat of neither, a situation that seemed to lay the groundwork for a future of relative security. As for the episodic, disturbing, regrettable and mostly tragic history of Jewish collaborations, however circumstantial, with racists and fascists--e.g., Mussolini--it continues today with the rise of Donald Trump and Jewish extremists in Israel.

Growing up in Macon, Steve excelled at ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps, which still recruits students in high schools as well as at colleges) at Lanier High School, where he became adept at the operation of a rifle they gave him to keep and practice with at home, graduating from a bb gun he handed down to me, having taught me how to use it to shoot birds and squirrels.

The school was named after the revered Macon poet, musician and educator Sidney Lanier, whose Wagnerism New Yorker music critic Alex Ross has commented on but whose military service in the Confederacy he has not.

Ross keeps chalking up Wagnerites from a wide range of backgrounds in efforts to demonstrate that the composer's influence has been so great, so vast and varied as to subsume ongoing concerns about his legacy of anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, and notwithstanding Lanier's later distancing of himself from his Confederate service and support for slavery, efforts continue in Houston to change the name of its Lanier Middle School because of the name's association with the Confederacy.

The move to rename Lanier Middle School is not the only such initiative. Also in Texas, this time in Austin, the school board voted to change the name of Robert E. Lee Elementary school. According to CNN, "the decision came amid a larger trend of questioning Confederate memorials across the American South, given the Confederacy's legacy of violence, racism and white supremacy."

More recently, as reported in the New York Times, the Washington National Cathedral, one of the nation's most prominent houses of worship, said that it will remove two images of the Confederate battle flag that have been part of its stained-glass windows for more than 60 years. When I discussed this story with my closest friend, Joel Bradley, a liberal Southerner-New Yorker and distinguished addiction treatment specialist in employee assistance programs who hails from Elberton, Georgia and whose grandfather fought in the Confederacy, we both wondered if some efforts to eliminate emblems of historical events haven't gone too far.

Though the name of Richard Wagner is not the equivalent of the swastika or Confederate flag, and it's certain that Wagner will continue to be a leading presence in musical culture, it seems likely that in much the same vein that Southern institutions and landmarks are being scrutinized and cleansed of Confederate symbols and associations, future generations of Germans, Europeans and others will deprioritize Wagner from consideration for some name designations he might otherwise have claimed--for institutes, schools and landmarks.

At home and with straight faces, Steve, Ellen and I would march around the room singing the Christian hymnals we had to sing at school. (Our parents advised us to just mush-mouth any references to Jesus.) "Onward Christian soldiers, marching off to war, with the cross of Jesus...Jesus loves me, yes I know, Father Bible tells me so." And of course, "Dixie": "Oh, I wish I were in the land of cotton..." To say that old times there in Dixieland were not forgotten, specifically the glory days of the plantations and Confederate heroes like Robert E. Lee, whose birthday we still celebrated at school, would be as big an understatement as you could make about the post-Reconstructionist South we called home.

We were too young to have a real awareness of our outsiderness, even as we could sense the distress it caused our parents. Though my father seemed welcome in all circles, following the period of his medical education when many institutions had quotas for Jews, my mother's encounters with the shut doors of the Junior League--remember Ms Hilly in The Help?--were hurtful.

At home, meanwhile, our parents tried to acculturate us. Dutifully, I practiced piano, which I had no real penchant for. For my first and last recital, I played "From the Halls of Montezuma To The Shores of Tripoli." I guess our involvement in Libya goes way back. Who knew? I was never to become a musician, but my love for music did evolve from childhood crushes on Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Jerry Lee Lewis, Theresa Brewer and Brenda Lee, whose hairdresser I was to meet and befriend years later at the baths in Fort Lauderdale. His clientele was mostly elderly women in senior residential facillities. At their first session, he would patiently explain: "This is a comb, not a wand." From my first vinyl 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) rock-and-roll records to Broadway show LP (long-playing) albums like My Fair Lady, I eventually moved on to what became the first great love of my life, opera, and its Grand Poobah, Richard Wagner.

In those same childhood years I labored over one of my first books, James Michener's The Bridges at Toko Ri, which won a Pulitzer Prize and was made into a 1954 Hollywood film starring William Holden, Grace Kelly, Frederic March and Mickey Rooney. It's about the war with North Korea which, like the Civil War, and for that matter the Crusades, and for that matter again the American Civil War, we are still playing out. Though I never became a voracious reader, my interest in things literary developed in tandem with my love for music and opera.

At school we read The Jungle Book and Lazy, Liza Lizard, and our teacher would model the costumes she acquired from her around-the-world tour, one of which, a kimono, set the stage for my first opera, Madama Butterfly. I can't remember at which of Macon's two historic universities it played--Mercer, named for Jesse Mercer, a prominent Baptist minister, or Weslyan College, one of America's first women's colleges and a birthplace of alumnae associations and sororities. More than a half century later, In "Racism on Campus, Stories from New York Times readers," one Weslyan graduate recalled, "The racial diversity at my college was basically all brochure pictures and no substance."

Meanwhile, it was just this otherness that seemed the matrix of my brother's inimitable intelligence and wry, often twisted humor. Sensing our difference from the mainstream of Southern society, Steve, my sister and I were drawn to black singers of the times who appeared locally and later became legends, especially Little Richard, who in fact hailed from Macon. Just as these musicians were breaking through racial barriers by sheer talent, appeal and box office success, they gave inspiration to all outsiders, Jews prominent among them. But it wasn't until our move to Chicago that I attended my first concert with one of these legends--Ray Charles, whose "Georgia on My Mind," written by Hoagy Carmichael in 1930, became the state's official song in 1979.

Enter Jayne Mansfield and her 1956 film, The Girl Can't Help It. The title song by Little Richard, and two other of his biggest hits, "Ready Teddy" and "She's Got It," helped make what was otherwise this B-est of B movies into one of the richest assemblages of period pop music on film, featuring such other leading artists of the day as Gene Vincent, Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran, Julie London, The Platters, Ray Anthony, Johnny Olenn, The Bell Boys, Abbey Lincoln, Eddie Fontaine, and Teddy Randazzo and the Three Chuckles. Outside the theater where the movie played, incidentally, was where the Klan was said to have carried out its lynching.

The year before, Mansfield's co-star Edmund O'brien was the villain in another film that offered rich hearings of pop era greats, Pete Kelly's Blues. Starring Jack Webb of early television cop drama Dragnet fame and the legendary Peggy Lee, it had cameos with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, and, as a cigarette girl, Jayne Mansfield. Squeak!

It's hard to imagine more fertile soil for someone with a good ear for music and talent. Even in the heyday of the Mudd Club, however, I don't remember Steve ever singing a refrain or humming a tune in a way that reflected straightforward affection for it. Rather, in those 1950's years of our childhood and adolescence, he would exaggerate and parody singers and songs, the hits we all loved but especially the crooned renditions of standbys like "Fascinating Rhythm" by popular B-list singers like Julius LaRosa, Marguerite Piazza, Perry Como and Dinah Shore.

What Steve seemed to be trying to convey was his weisenheimer sense that the decorum we were seeing and hearing in mainstream entertainment and society was artificial, insipid, sentimental, ennervated, desexed, hypocritical, and funny as such. In Steve's sensibility, that artifice became the basis of what Susan Sontag would later become known for identifying as "camp." Steve was not gay, but he had what we gay people thought of as our special instinct for subverting social pretense with exaggeration, humor, affection and nostalgia. A droll and insightful if never exactly hilarious observer of people, and especially of 1950's culture, Steve was nonetheless an offshoot of the Jewish comedians we saw on our 12" black-and-white Motorola TV who endeared themselves to mainstream America by using wit and facetiousness to upend provincialism and prejudice--Groucho Marx, Milton Berle, Sid Ceasar, Phil Silvers. Later, there was Lenny Bruce and eventually Woody Allen. At his most imaginative, Steve was the creator, operator-in-chief and behind-the-scenes (mostly) star of a Cabaret-style panoply of retro and cutting-edge fashions, design, theater, personalities, politics, happenings, musics and arts. At his more sardonic and reclusive, he was a shadowy figure from a performance artwork by Mudd Clubbers Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed.

How else to react to what was expected of Steve--daily ROTC exercises and daily application of the phylacteries my mother's Orthodox Jewish mother insisted on? Obediently but with that mix of pride and irony, arrogance and defiance that became hallmarks of his personality, Steve did both, meanwhile excelling among his genteel, gentile Southern peers in two key areas. Though he had to endure a lot of hazing, doubtless some or more than some it anti-Semitic, he became an Eagle Scout, a serious achievement for any young man at that time; and he was so good at golf, the ultimate entree into Southern male society, that his picture was featured with several other state champion team members in the Macon Telegraph.

Steve was on his way, to be sure, but from Georgia to where? I don't think Steve ever thought of himself as belonging to the beats or any other movement, school, party, decade or even generational divide. Like people in recovery, and as stated in their preamble, Steve was not allied with any sect, denomination, politics, organization or institution. But it was Jack Kerouac rather than recovery that could have been speaking for Steve when he wrote in 1957, "Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me, as is ever so on the road."

to be continued