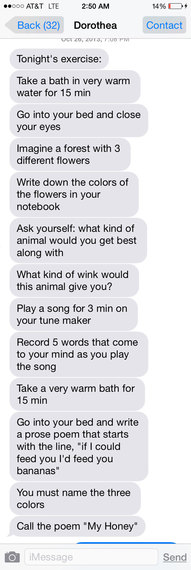

If you ask Dorothea Lasky for writing advice you might get the following text message:

Lasky was my very first poetry professor at Columbia, where I'm studying for my MFA. I knew I was getting a teacher of ferocious passion and penetrating psychological insight from her poetry, which I had in read in The New Yorker, the Paris Review and in her four poetry collections.

But I wasn't prepared for Dottie. She wears leopard print onesies and more plastic jewelry than all the tickets can win you at a Chuck E Cheese. Her eye contact is ferocious--it'd be lunatic if it wasn't so tender.

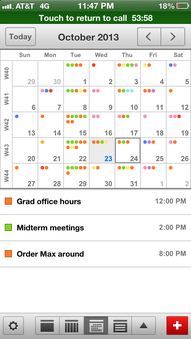

A month into our time together, I told Dottie I wasn't writing frequently enough, that I felt tense and was overthinking when I went to write. Her response was to send me a text message every night for the entire month of October, 2013. Here is her iPhone calendar from the time (the orange dots mark nights to "Order Max Around"):

The text messages contained what she called "exercises." That October, I didn't go out on Saturdays. I did Dottie's exercises. One could call them writing prompts, but they were more like lavish, personal rituals. She made me text her photographs of my furniture, my bathroom cabinets' contents, my fridge, my shoe collection, glasses collection, and all of my pens. From this digital temple of my ephemera, she would choose sacramental objects for a ceremony. Every night I turned somersaults, guzzled a rainbow of different fruit juices, plunged into scalding baths--all the while jotting down phrases on a big yellow legal pad. The end of every ritual culminated in a poem. As time passed, a sense of the spiritual and sacred suffused my apartment and all of its contents. It had all become part of my poetry--the thing that mattered most to me in the world. Though Dottie has never been in my apartment, she haunts every lamp, toothbrush, and stuffed animal.

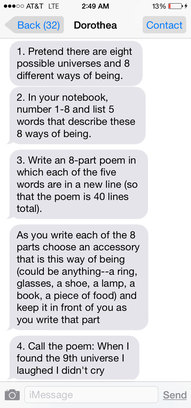

When I told Dottie I wanted to write a big poem, a grand poem, she gave me The Universe Prompt:

The night after I completed the Ninth Universe, I wrote a Tenth. More Universes followed and eventually, with her earlier prompts, they formed the bedrock of my first chapbook, AEONS, winner of the 2014 Poetry Society of America Chapbook competition.

I told Dottie I wanted to interview her on her teaching philosophy on the occasion of the release of AEONS: it's a rare thing for a book of poems to be born in a single classroom. I wanted her to discuss her educational philosophy, which is idiosyncratic in the extreme.

MR: All of your writing advice to me has always felt utterly personal. The writing prompts you gave me required you to study my apartment and also deeply engaged with things that matter a lot to me: animals, neon colors, fruits and vegetables. Do you think you need to learn all about someone before you can help them make art? What is the link between intimacy and teaching--teaching poetry or anything else? And how would you have taught me if we didn't have so much in common?

DL: It sounds a little silly to write this in actual words, for public consumption no less, but I do believe we were actually blessed to have found each other in that classroom. As soon as you opened your mouth, I thought, "Oh, I like him." And it was fast magic from there on out. It was so easy to do this work with you for a lot of reasons. First of all, your instincts towards the poem are always littered with utter genius. So, when I gave you prompts, I knew you weren't going to change these moments into any old thing. Second, you are so brilliant, in a way that is different than artistic genius. You have a brilliance in the ways in which you have consumed and can convey information, and you brought to our work all of the great things you have read and thought of, which are many. Third, and most importantly, and most rare, you are more open than anyone I've ever met, you take what is given to you with a kind of open stare, the immortal poet's stare. We had ideal teacher-student intimacy, because we have so much in common yes, but also because your openness made me more open. I didn't have to perform any authority, you weren't testing me, you simply wanted to create and grow, and this made me soft and ready to help you grow.

MR: Well I obviously like that answer. We were very lucky. But what if a teacher has an oversized class and very limited class time, what would your advice be for someone in that situation?

DL: I think the key to any sort of good teaching is to utilize the classroom as a performative space and you can make the classroom a stage, no matter how many students you have. Practically speaking, I would tell this teacher to try and give her students as many options towards completing an assignment as she can, with at least one in each of Howard Gardner's types of intelligences (visual/spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, linguistic, logical-mathematical) and then include an opportunity for students to suggest their own alternatives to the assignment. She should also use serious group work, where students have to build complex products towards her learning objectives, suggest each student record her learning in the class, and include several types of semi-public performances so that students can demonstrate what they have learned (i.e., a poetry reading, an art show, a science fair).

MR: How was prompting a long poem into being different than prompting a shorter poem?

DL: Poetry exercises are very often about prompting the shorter poem. When I prompted your long poem, it was a relief as a teacher that I knew you would stay with the moment of the poem for a while, that you would consider the issues of it deeply, that you would think about making a tapestry of music that had time to expand. I've always favored the kind of classes that were obsessively focused on one thing, like a class on a particular type of Flowering Maple versus a class on flowers. When you make an exercise for a poet to write a long poem you beg for obsession. As a teacher, this is what I like to beg for.

MR: You're a spiritual person and spiritual poet. Your work with me, as I saw it, was mainly teaching me how to enter and exit a trance. You love astrology, fate, and ritual. Do you think one needs trance states or some engagement with the spiritual realm, to write poetry?

DL: When you came to me, you said, "my mind is blocking me from writing poems," and I knew I had to help you rid yourself of the mind. I've always felt that when you tap into the part of the self that writes poems the self becomes beyond the mind. I go back and forth if I think this sort of state is part of the other world or is part of this one. I tend to favor the idea that people are creative from what the world gives them versus just being touched by the divine, because I think the former allows for the possibility that everyone can be creative versus just a chosen few. Whatever we want to call it, I think poets enter a space which is another reality when they write a poem, and that this is a great space to exist in for as long as possible.

MR: And I've heard you self-describe as a hoarder: your wrists are constantly clacking with new bracelets in your purse, and you always carry at least three pairs of glasses at once. Your spirituality seems deeply embedded in this love of physical objects--almost plastic-totem-worship. Could you talk about how material objects play a part in your spirituality and your poetry? How do material objects play a role in your teaching?

DL: Yes! You and I have discussed this a lot and have even exchanged many totems. Object-based learning is very important to my pedagogy and part of what I used as a foundation to starting a poetry school I co-direct called The Ashbery Homeschool and what I will use to create future educational programs. I think when we create and think from objects our thoughts have weight that more directly access the imagination. This may seem counterintuitive, as many times we assume thoughts beget thoughts. But I think the physicality and spirituality of an object (bearing with it the culture, individuals, and society that made it) is a symbol of the object-like schemata that exists in our imaginations as we create new things. I guess this reason alone explains my (very overwhelming) hoarding tendencies.

DL: OK, now is my turn to turn the tables on you. After we did this work together, I wonder: did it influence your future writing in any way? Also, you are a teacher too and will be teaching writing semi-full-time next year as an instructor in the Undergraduate Writing Program at Columbia. Will you use any of what we did in your classroom?

MR: Of course it influenced my future writing! I think I'm now a writer of faith--faith in the senses. If halfway down the page my hand stops writing, all I need to do is perk my ears up or reach into a cabinet and pull out a trinket, and my senses will provide me the rest of the poem--the world will provide me the rest of the poem. As for my future teaching, I want my students to be swept up in their writing projects, for their writing to be their companion, as AEONS was for me during our time together. I also want them to be comfortable radically revising and reimagining their projects midstream as you taught me to be.