"Treat objects as if they had nervous systems." Bruce Fertman.

There's an old porcelain telephone on the stage. It's only there because in the second act it is written that a character answers the phone to hear news of an arrest. After this single moment the telephone plays no more role, contributes nothing to the on-going drama. It's forgotten by audience and actors alike. Its existence fades.

We tend to treat most objects like they are minor props in a play. They are only real when, and in so far as, they have use to us and the plot we are enacting. They have no voice of their own, no 'life' other than that contained in our script. They are not even background.

If we can give up this idea we realize that the simplest of objects offers us a more interesting possibility. Each has a dual existence, like light which is simultaneously both wave and particle. Firstly, objects are entirely, indifferently themselves, their fundamental nature un-impacted by our dramas and projections. My glasses case does not change in the slightest degree according to my mood or the injustices that have been done to me. And yet they also reflect back to us precisely and unselfishly our own mode of being in the world. In each of these expressions they render us service.

There is, for example, a quality of calmness in the way a book simply rests upright, snug with others, on the horizontal shelf. We can interrupt and lose this quality when we grab for it, or share in and imbibe it as we pick the book up. There is a generous willingness to be used in the warm swell of a pot and the gleam of a tea cup. And a sharp knife will offer us in each cut a lesson in ease and gracefulness should we cooperate with it. The table settles firmly on the floor before us in order to support our work, the bicycle asks to be used, and the sword or the paintbrush or handsaw whispers a language full of texture and resonance to the firm hand that also has the space to listen.

If this is so, even more so with living 'objects.'

Walk in the woods. Run by the lake. Observe the ordinary grass. Look with humility. Nature can be abundant and overflowing, yet it rarely crowds, or finds itself untidy, because it understands the private yearning at the heart of every thing reaching for a certain relationship and space. Because it feels the kernel of each seed wanting to mingle the rich dark ground with the splendid breeze and sunlight; the horizontal and vertical, the down and the up, the single place and the movement.

How do we humans make things so untidy? How do we get things so out of place?

Because we are so busy we ignore the quiet murmur of each thing for place, connection and scope, and we have allowed those who are the most busy this way to have so much power.

We fail to see relationship between things. Because we manipulate rather than touch, we grasp rather than hold, we reach forward with the hand while we shrink back with our awareness, handling the world for ends that we have only thought about, not felt. Because we accumulate, accumulate and forget to experience.

We have an idea of things. We may separate the cup from the table, but we collapse every cup into this broad notion of cup-ness. We miss the felt experience of this unique cup and the way it sits up so perky on the grainy table surface, gleaming just like so in the 3pm sunlight of this autumn day. Our idea of it eclipses it.

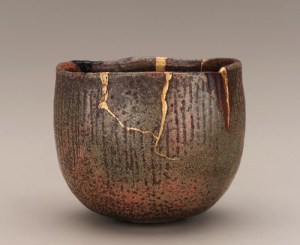

Things speak to us of their own history. Particularly if they are made by us, they speak of the quality of care that went into their own making. The faulty and imperfect asymmetry of a hand-made pendant, or a repaired pot, can breath more balance into our system than the perfect symmetry of a factory product. The smoothest pebble weighted in the hand can be more interesting to the touch than the curves and sophisticated ridges of mass produced plastic. When we surround ourselves with such ill-made products we create a muted environment, that leaves us numb and seeking satisfaction somewhere else. Always somewhere else.

The relative silence of such indifferently made things actually speaks to us of a deprivation and our own carelessness, like the brooding sulk of a neglected child at the table. Yet even they would warm up and speak if we shifted. If we paid attention.

Pick up the pen in front of you now as if it has a nervous system. Or another small object. It doesn't matter if it is humble and cheap, or fancy and expensive. Pick it up gently, yet with precision and it will find and communicate its own tiny dignity. Pick it up as if you would leave an un-smudged fingerprint for posterity. Be sensitive to the exact balance of firmness and care that such a little object asks of you. Pay attention to the particular dexterity it calls forth in you. Feel its coolness and its density. Let its balance and the small mercury gleam on the nib enter your awareness. Notice when you do this how a little more aliveness soaks up your wrist into your forearm and beyond, as if inspired in through the fingertips. Breath softly. Feed your heart with it. Allow yourself to be very simple for this moment.

Where does the world of objects start and stop? Where does an 'it' start becoming a 'you' or a 'me.' This is not clear, for the world of objects has no stable borders, and in actual practice includes much of what should be a 'you' or even an 'I.'

Whenever we 'lose touch', we make objects of our children, our partners, our friends, our work colleagues. We also make objects of our selves, particularly our bodies, but also our particular forms of neurosis, which we want to push away. We treat them as if they are not a strand of our living substance, integral to a rich, embodied and complex subjectivity, but as a thing, to be manipulated and trained, grasped or pushed away.

So when we practice paying respectful attention to the world of 'its" around us, when we imaginatively invest them with an element of "you," strangely we find the by-product is that we also reinvest our own bodies with our own subjectivity. We reclaim our own I-ness from the it we abandoned it to. We take care of the scarf around our neck as we place it, and find that it offers us so much more than a barrier against the cold; the chance to reoccupy our bodies with loving attention.

Who would have known that the door to self-care is entered not through self-obsession, but through care of the world!

When I listen to the news it is easy to despair. There seems so little kindness, sense or intelligence in our story as human beings. Where can we turn to? Each other, certainly. But there is also an unflagging kindness, a willingness to help, in every 'thing' around us, easily offered if we should only pay gentle, respectful attention. This is a form of basic goodness in the world. An inexhaustible generosity that exists everywhere, dependent only on our skill with awareness, awaiting our arrival in the place we already live in.

------------------------------------------------

John Tuite founded The Centre for Embodied Wisdom and Clearcircle. He now works as a leadership and life coach, and consultant. He is a qualified Leadership Embodiment teacher and a continuing student of Wendy Palmer, founder of Leadership Embodiment. He also teaches a range of embodiment skills from breath work to mindfulness and energy work/qi-kung.

This article also appeared on Kindness Blog.

------------------------------------------------