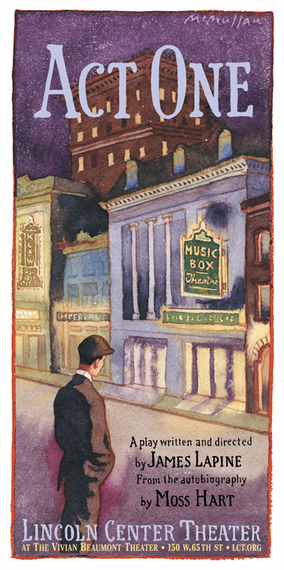

Moss Hart -- more than fifty years after his death, his name is back up in lights on Broadway with the smash new stage adaptation of his 1959 memoir, Act One, at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre. A Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winner, a celebrated playwright and admired director, Hart dazzled the world of show business with his brilliance and innovation.

With George S. Kaufman, Hart was half of one of the most successful comedy-writing teams of the century; there never has been another pair to match the success or enduring popularity of Kaufman and Hart. Moss Hart's brand of wise-cracking, fast-paced humor had its roots in the grimy streets of his immigrant childhood, and it was enriched with the brittle humor of the Roaring Twenties. This talent came to full glory in the grimmest days of the 1930s as Depression gripped America and Fascism swept across Europe.

An evening of Kaufman and Hart was the brightest the Broadway theater had to offer and their impact has been felt ever since -- in television, the movies and on stage. But based on the reviews, James Lapine's adaptation of Act One is in the best Moss Hart tradition.

For three decades, Moss Hart was one of the most familiar names in show business. From his impoverished childhood in the slums of Manhattan and the Bronx, which he described in Act One, he rose to phenomenal fame at the age of 26, with the production of Once in a Lifetime, written with George S. Kaufman. In the next decade, he and Kaufman wrote eight plays, two of which -- You Can't Take It With You and The Man Who Came to Dinner -- are among the most frequently performed works in the American Theater. The Man Who Came to Dinner was a smash hit when it was revived on Broadway in 1999 starring Nathan Lane. You Can't Take It With You, a zany tribute to eccentrics and a devastating broadside against big business, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937. Its film adaptation directed by Frank Capra received the Academy Award for best picture of 1938. If Moss Hart had written only those two plays, he would be worthy of our attention today.

But it didn't end there. Before and after he and Kaufman parted professionally in 1941, Hart worked with some of the most creative spirits in show business. He and Irving Berlin collaborated on three shows, including As Thousands Cheer and Face the Music. In 1935, Hart took a cruise around the world with Cole Porter. When they returned, Porter and Hart had written a musical, Jubilee, which introduced the hit songs "Begin the Beguine" and "Just One of Those Things." (In 1998, both Jubilee and As Thousands Cheer were revived in New York.)

On his own, Hart conceived Lady in the Dark (1941), a ground-breaking musical about psychoanalysis, drawing heavily upon his own treatment by two of America's leading therapists. He wrote screenplays for several of Hollywood's most popular films of the post-World War II era, including Gentleman's Agreement (1947), the Academy Award-winning expose of American anti-semitism. Then, in 1956, Hart drew upon all of his skills as a showman to become the principal creative force in the production of the greatest of all musicals, My Fair Lady.

Wealth and fame enabled Moss Hart to enter a world unimaginable to the boy from the Bronx. With Kaufman's introductions, he became a key figure in the legendary Algonquin Round Table set, and his close friends included Alexander Woollcott, Dorothy Parker, Harpo Marx, Edna Ferber, Helen Hayes and the Gershwins.

"Moss Hart!" recalled his agent, Irving "Swifty" Lazar. "[H]e was close to being the god of the theater world. George Kaufman and Maxwell Anderson were right up there, but Hart embodied the glamour, wit, and charm of Broadway at its popular best. In my mind I see him at the center of the circle of Broadway's elite: tall, lean, handsome in an angular way, with a carved wooden pipe in one hand and a cocktail in another, holding forth with an effortless series of witty remarks."

Lazar's vision was precisely the image Moss Hart spent a lifetime creating, consciously seeking to compensate for the poverty of his youth. Along the way he changed his own life story, eliding episodes that delayed the plot, adding a bit of luster to the moments that seemed dull, editing entirely the painful or the embarrassing. Still, Moss Hart carried the dark, brown taste of being poor with him every day of his life, even after he left the hardships of his youth far behind. Understanding the youth is essential to appreciate the man. "Look how it was then," he once advised, "and see how it is now."

The son of immigrant English Jews, Hart's early memories were of an extended family: his parents, his deformed younger brother, Bernard, his mother's father, and his mother's sister, Kate. His father and grandfather scraped out a living rolling cigars in their dark tenement apartments. Until he was ten, Hart's beloved Aunt Kate was the center of his life, and it was she who would introduce this shy, gentle boy to the world of the theater.

"I have a pet theory of my own," Hart wrote in Act One, "that the theater is an inevitable refuge of the unhappy child," enabling him to create a world of his own, a "revolution and a resolution of his unconscious difficulties."

It was Aunt Kate who raised the curtain on that world for young Moss. In later life, upon seeing Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire, Hart realized that Blanche Du Bois reminded him of his aunt -- "a touching combination of the sane and the ludicrous, along with some secret splendor within herself." There were more similarities to Blanche than Hart was willing to admit; she also had a far darker side, one that would come to dominate her and ultimately separate her from the boy she loved. But for them both, for a few precious years, the theater was a realm of fantasy, one that Kate shared with a sad and lonely little boy.

Supported by her father and then her brother-in-law, Kate never worked while under the Hart roof. Yet every night, she slipped away to the theater, her tickets and finery underwritten in part by wealthy relations in England, to whom Kate appealed after her father died. When she returned from the theater, she would join her sister and little Moss by the stove in the kitchen and vividly recount every detail. Later, Moss would suggest that in such moments his life was transformed: "Here is how it happened -- here is where the door opened -- this was the turning point."

When Moss was seven, Kate arranged for him to leave school every Thursday afternoon for a matinee at the Alhambra Theater in the Bronx, where he studiously observed many of the great vaudevillians of the day. Then he graduated to Saturday matinees at the Bronx Opera House, where he saw real, albeit second-run plays. And at night, Aunt Kate would grandly depart alone for Broadway, returning to share her accounts with the boy who could never hear enough about the stage.

Two events shook this early pattern in Moss Hart's life. The first was the automation of cigar manufacturing in the early 1900s -- an event that destroyed the cottage industry supporting thousands of people like the Harts in tenements across New York and other major cities. Hart's grandfather died soon after, and Hart's father never really recovered. He tried factory work but wasn't suited for it and later ran newsstands and stationery shops. The family's principal source of income came from boarders.

The second event, even more pivotal, was the fight between Moss's father and Aunt Kate. Her indifference to the Harts' financial plight provoked a disastrous confrontation and her banishment from the household when Moss was ten. Family lore has it that there was more than indifference on Kate's part; she appears to have formed an attachment -- in Blanche Du Bois style -- for her brother-in-law, creating a tension that simply would not do in the Harts' world. For years after, Moss did not see his aunt. In later years, however, she would reappear -- in fact and in fiction.

Nevertheless, Aunt Kate's spirit infuses much of Hart's work, notably his 1938 play, The Fabulous Invalid, written with Kaufman, a cavalcade of the American theater in the early part of the century. One can hear the magical accounts of Aunt Kate through the actors' voices as they describe all the grand theatricals of the century's early years, perhaps in the very words she had used in the Harts' kitchen decades before.

Generally those nights were illuminated by candlelight -- not for romance, but because the Harts could not spare a quarter for the gas meter. Moss and Bernard Hart stumbled to bed in the dark and shivered in the cold. Small wonder a child in such a bleak world would be transported by the tales of a loving aunt with her eye on the footlights.

The sting of poverty didn't end at his parents' front stoop. Moss Hart was 26 before he achieved his first true success on Broadway. He was forced to quit school at thirteen to help support his family. The years in been were remarkable, not because of the Harts' poverty, but because Moss had the vision and the strength to carry on, year after year.

He began this quest even before he left school, with a part-time job in a Bronx music store, which afforded him his first visit to Times Square. He spent two years in a clothing factory and also sold classified ads for the New York Times. Then he landed a job that marked the turning point -- he became the office boy for Augustus Pitou Jr. "King of the One-Night Stands," whose theatrical company traveled from town to town across America in the days before radio, television, or the "talkies." It was for Pitou that Hart wrote his first two plays, produced when the writer was still in his teens. Their failures gave Hart an early taste of defeat, but they also offered him a sense of what might be his if he wrote a play that succeeded.

Hart struggled through the 1920s, spending his summers as a social director at camps and hotels in upstate New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont and his winters as director of small theatrical groups around New York City. Then, sudden, dazzling success came with the production in 1930 of Once in a Lifetime, which Hart wrote with George S. Kaufman.

Their partnership was uneasy from the beginning. Kaufman was 15 years older, the seasoned veteran of a dozen hits. As theater editor for the New York Times. Kaufman was a formidable force on Broadway. But, as their friends were quick to attest, Kaufman had never met anyone quite like Moss Hart. Young Hart was ambitious and brash, admiring of Kaufman yet envious of his fame and wealth.

Edna Ferber (Kaufman's collaborator on several of hit plays including The Royal Family and Dinner at Eight) recalled the youthful Hart this way:

When I first met Moss Hart, he had just been discovered hidden in the bulrushes. A year later, a tall gangling youth, stunned by his own spectacular success, possessed of an extraordinary zest for life, he had been turned loose on the slippery race track that was Broadway and New York and the world of creative writing. To his amazement, he found himself one of a hardworking, realistic, laughing, talented group made up of people such as George Kaufman, Lillian Hellman, Marc Connelly, Aleck Woollcott, Dorothy Parker, Herbert Swope, Helen Hayes, George Gershwin, and many others. Moss was like a young spindling colt turned out on the track to compete with Seabiscuit and Man O' War. He promptly surged ahead and outdistanced many of them. He was younger than most; much younger than some. For me he was, I suppose, the son I'd never had -- you know, mine son de doctor.

If Ferber became Hart's theatrical mother, surely Kaufman was his father. For all their differences, the two men came to love each other and to depend upon one another's advice and presence, a bond that continued long after their formal collaboration ended.

Both men were haunted by emotional problems. Kaufman's phobias were legendary. He disliked physical contact with others, yet he was known as a great lover (When actress Mary Astor's diary, containing graphic accounts of her amorous relationship with Kaufman, was published in 1935, he had to flee to Hart's home to escape the press and the police.) "George was scary," observed Hart's widow, Kitty Carlisle, many years later. He was intimidating -- to strangers, to waiters, to cab drivers, and to small children. But he was utterly loyal to his close friends, even to his ex-wife. Hart, as we'll see, wrestled with his own internal demons.

Yet, together they banished all gloom to produce some of the stage's funniest plays. Certain scenes from You Can't Take It With You and The Man Who Came to Dinner inevitably bring the house down. From souls in pain, Kaufman and Hart evoked smiles across the faces of Depression-ravaged America -- smiles that have not faded.

In her 1988 autobiography, Kitty Carlisle Hart observed how much success in the theater meant to her husband: "Going to California in our luxurious drawing room on the Twentieth Century Limited, he would look out of the window when we went through the Bronx and scan the tenements looking for his old house. 'There,' he'd say, 'that's where we lived.'"

Other times, standing on a hot summer day in the Harts' swimming pool in Bucks County, built with the money he earned writing Lady in the Dark, his mind would return to his youth:

It's five o'clock. I'm getting into the Subway on Eighteenth Street. So is the rest of New York, and we're all taking the local. The first stop is Twenty-third Street; the second is Twenty-eighth Street." He would name each stop on his way to this destination in the Bronx. Then he would continue his story. "I am trudging home from the subway and my mother is hanging out of an upper window, watching for me. 'What's for dinner, Ma?' I call up. 'Lamb stew.' 'Lamb stew, on a boiling hot night! Well, I think I'll take a shower.' 'No,' my mother answers, 'Mrs. Steinberg had to give her cat a bath and the shower's all stopped up.'

Life in Bucks County was an extension of what Moss and Kitty Hart enjoyed in New York; down the road, George and Beatrice Kaufman had their own estate. "They and Moss shared their guests every weekend," Kitty Hart remembered. "If it was Saturday dinner at the Kaufmanns, it was Sunday lunch at Moss', and the next weekend it would be reversed."

There was nothing rustic about the Hart farmhouse; in 1947, an appraisal of the home listed each room's contents and their value (some $73,000 worth, more than $1 million in today's value, including motion picture equipment in a screening room and four guest rooms named according to the color of their décor -- rose, yellow, green and blue.) Hart believed his guests should be kept busy. Word games, bridge, swimming, croquet and tennis were special favorites. Singers were encouraged to sing, pianists to play. In good times, Moss Hart was at the center of all this, a charming, energetic host.

But Hart's life was not all glittering weekends and boisterous good times. A dark, as-yet-unexplored shadow of duality, shrouded by depression, enveloped this charming and funny man of the theater. As Malcolm Goldstein observed in his 1979 biography of Kaufman:

...[T]he rapidity and depth of the change in [Hart's] way of life proved punishing to his emotions. His adjustment was difficult. To accomplish it he turned to psychoanalysis in 1933 and continued with it for many years...Perhaps of all the uses to which he put his new wealth, this expenditure was the wisest of all, since not only did it make possible the continuation of his career, but eventually the sharing of his life in marriage.

Moss Hart believed in psychoanalysis and had reason to be grateful for it. One of its principle benefits came in 1940 when, with composer Kurt Weill and lyricist Ira Gershwin, Hart wrote and then directed the first (and still the best) musical about the mysteries of the mind, Lady in the Dark, starring Gertrude Lawrence and Danny Kaye.

In the early years of his success, Moss Hart appeared to be a confirmed bachelor. In him, one found a bit of Henry Higgins, the misanthropic hero of My Fair Lady, and even more of Liza Elliott, the troubled heroine of Lady in the Dark, who never could make up her mind, and thus avoided a decision to marry.

But in 1945, that seemed to change. Hart began courting the singer and actress Kitty Carlisle. It was his first serious relationship with a woman.

They had met a decade earlier, in 1935, when she was 26 and he was 31. It was on the set of M-G-M's A Night at the Opera, in which Carlisle was featured with the Marx Brothers. Although Kitty had appeared in several musicals on film and in a hit production of Rio Rita on Broadway, this would be her most famous role, one that secures a special place for her with movie buffs of every age.

Hart had come to Hollywood -- where Kaufman was working on the screenplay of A Night at the Opera -- to look for a leading lady for Jubilee, he musical he and Cole Porter wrote on their round-the-world cruise. Hart and Porter visited the M-G-M set, and Harpo Marx offered to introduce them to Kitty Carlisle.

65 years later, Kitty would recall that she was so excited at the prospect of meeting "two of my heroes," that she ran across the sound stage: "A movie set is one big booby trap, with electrical boxes, plugs and coils of wire all over the floor. I tripped over one of them and fell flat at Moss's feet."

When they married in 1946, Kitty wrote that Hart "finally set me firmly on my feet."

To friends, however, it seemed as though the warm, generous Kitty Carlisle had planted the frenetic, troubled Moss Hart firmly on his feet.

Many wondered about the marriage, and for years questions have been raised about Hart's sexuality. Interviews by this author of both Robert Goulet, the actor, and Dr. Glen Bowles, a New York psychologist who claimed to have been Hart's lover in the late 1930s, revealed a deeply troubled playwright. Steven Bach's biography, Dazzler, attempted to explore this topic, but kept running into Kitty Carlislie's roadblocks. Hart himself wrote that in the years before his marriage, he was utterly consumed with work and the desire to escape poverty. Inevitably, his years of psychoanalysis and bachelorhood would fuel questions about his life and loves.

Until Kitty Carlisle, Hart seemed satisfied with solo housekeeping in a Manhattan pied-a-terre and in an 18th Century farmhouse in Bucks County. No woman had been able to enter his private life. Perhaps he was unable to find a woman with whom he could share his sense of style and his passion for work in the theater. Kitty Carlisle did.

Indeed, no one was quite like Kitty Carlisle. In many ways, her story is as fascinating as Moss Hart's. Shrewd, beautiful and talented, she attracted suitors as diverse as the financier Bernard Baruch, Nobel Prize-winning novelist Sinclair Lewis, George Gershwin and former New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey.

Kitty's mother, Hortense Conn, was an ambitious doctor's widow from Louisiana who took her only child abroad as a teenager in search of a royal alliance. That failed, but young Kitty's vocal training positioned her for a career in theater and the movies. Still unmarried in 1945, Kitty viewed the 41-year-old Hart as almost precisely the kind of man her mother had groomed her for. They wed in August 1946, and spent their honeymoon acting together in The Man Who Came to Dinner at the Bucks County Playhouse. "I had married my prince -- not of the blood, but of the theater," Carlisle concluded.

They lived together as theatrical royalty, sharing a fabulous 15-room apartment on Park Avenue, a summer house in Beach Haven, New Jersey, the farm in Bucks County, and in rented homes in Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Palm Springs. The sensible Kitty Carlisle, who had memories of living from suitcases in hotel rooms, understood the demons that fought within her husband. Instinctively, she seemed to know how to bring out his best, and the rest she learned to accept.

She called him "Mossie." He called her "La Divina." Theirs was a charmed world of literary, theatrical, and political titans: publisher Bennett Cerf, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Dorothy Parker, Gertrude Lawrence, Katharine Cornell, the Lunts, Irene Mayer Selznick, Adlai E. Stevenson, producer Arthur Hornblow and his wife, Leonora. The Harts' world was culturally the most sophisticated America could offer at mid-century, with the theater its centerpiece.

Some who had only vague knowledge of his origins were puzzled, even irritated, at Hart's taste for luxury. Cartier's was his second home. His wardrobe was filled with hundreds of pairs of shoes, elegantly tailored suits, and fur-lined topcoats. He so thoroughly draped his body with jewelry that Kaufman, a man of far simpler tastes, once dryly greeted him: "Hi-yo, Platinum."

Edna Ferber wrote of Hart's love of luxury: "He is monogrammed in the most improbable places. Just as he stands he is worth his weight in monogrammed gold bouillon; gold gallus-buckles, gold belt buckle, gold garters, gold and seal billfold, gold pencil, gold pen, gold and platinum cigarette case, gold bottle stoppers."

Hart found comfort in his possessions. These were tangible signs that he had made it, like the wad of cash he had picked up at the box office of the Music Box Theater the morning after Once in a Lifetime opened. And as long as he was single, and as long as the money from his big hits with Kaufman kept rolling n, his obsessive shopping posed no real problems.

But by the early 1950s, when he was married and supporting two young children (Christopher, born in 1948, and Catherine, born in 1950), the strain of several expensive homes, servants, travel, and entertaining began to threaten his security. At one point he was so distressed about money that he sold his personal papers to the Wisconsin State Historical Society for $60,000. Near the end of her long life, Kitty Hart still seethed over the sale -- about which he didn't consult her, even though he included some of her papers as well. With his family he traveled to Hollywood to write for films. Hart suffered three heart attacks between 1954 and his death in 1961. Were these crises brought on by economic stress? Could modern procedures -- notably the cardio bypass operation -- have added decades to the playwright's life?

All of his life, however, Hart delighted in a theatricality that was never limited to the stage. "When he went into a restaurant," his wife remembered, "He didn't just walk in; he made an entrance, his overcoat on his shoulders like a cloak; he looked like a great actor, and every head turned."

Kitty Hart carried on her husband's theatrical sense long after he died. On the television game show To Tell the Truth, she would make a grand entrance on every episode, beaming her best New Orleans-belle smile, draped in diamonds, feathers and furs. As chairman of the New York State Council on the Arts, she infused the organization with style because she had it. She learned much of it from Moss Hart.

After World War II, Hart entered a new and fertile period of creativity. Increasingly he devoted his energy to directing. (The last play he wrote, The Climate of Eden, which opened in 1952, was a failure.) Two of the musicals he staged were by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe -- My Fair Lady in 1956, for which Hart won the Tony Award, and Camelot in 1960. These stand as landmarks of the Broadway musical at its peak.

In the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, Hart made periodic sojourns to the West Coast, where he wrote the screenplays for such classic movies as Gentleman's Agreement, Hollywood's most powerful statement against anti-semitism; Hans Christian Andersen, which starred Danny Kaye as the beloved Danish storyteller, and A Star Is Born, Judy Garland's last great musical film.

Moss Hart's interests included work in politics and on behalf of his profession. He bravely spoke out against McCarthyism at a time when few of his peers dared. Of course, everyone knew he was patriotic: His contributions to the war effort included a hit show, Winged Victory (1943), which made more than a million dollars for the Army Air Forces relief fund. For ten years he served as president of the Dramatists' Guild, emerging as a visible and effective spokesman for the playwright's profession. Near the end of his life, he published a memoir that graced the New York Times best-seller list for 41 weeks, and became a film starring Jason Robards and George Hamilton, produced by his old friend, Dore Schary.

Moss Hart's unexpected death at 57 on December 21, 1961, was front-page news around the world. And though he was gone from the scene, the plays and films he created have remained to entertain, consistently, ever since. Now, with Act One on stage, he's back on Broadway in a big way.