Miles Feldman's, "Is privacy dead?" question has not settled the issue in 2012. In his February Huffington Post piece, Feldman outlined everything from online exhibitionism to government regulation and essentially said, "not so fast" to abandoning privacy: "Even in this new exhibitionist environment, anyone doing business utilizing user or customer information should make sure to implement fair and transparent privacy policies" (para. 7). "Is privacy dead? No. But we are changing how we feel about it" (para. 11).

Not so, say technology promoters from Palo Alto to New York. Across four trips this summer, including one to Dubai, I posed the, "So, is privacy dead?" question. To my shock, four different people looked me in the eye and answered "yes."

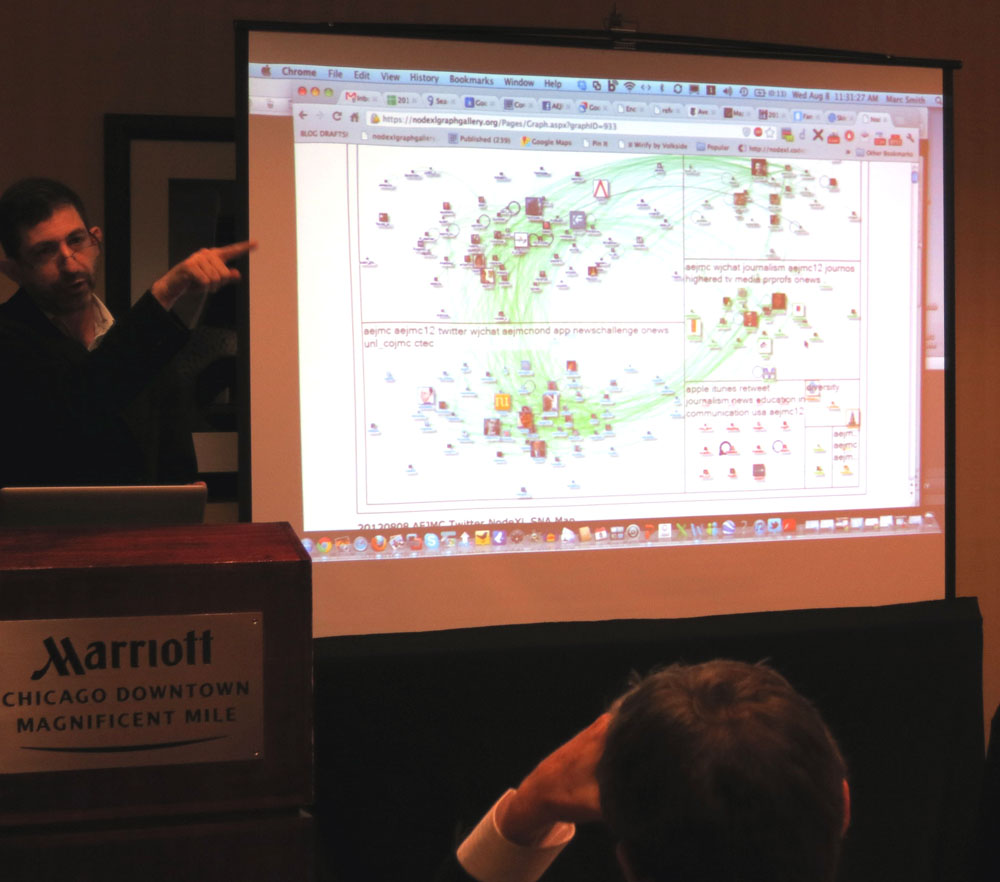

At the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) meeting in Chicago earlier this month (I'm a member), the Social Media Research Foundation's Marc A. Smith qualified the answer a little. In Germany they have a law protecting employee privacy, he said. But, not in the United States. Here, employers may analyze employee email for valuable patterns. The NodeXL software apparently allows for analysis of social networks of Outlook email users.

Computers can now read 130 million tweets per day, Smith said. He tracks daily snapshots of topics, such as Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party. "Anytime two people interact in email or otherwise," Smith said, "it leaves a graph."

"Nothing is private," Smith claims. He sees it as similar to an iceberg with about 10 percent "above the water line" and public.

Why should we care? Imagine an employer deciding to fire an employee for being at the periphery rather than the center of a company email social network. George Orwell must be smirking.

Newsweek magazine's Jessica Bennett also has asked the, "Is privacy dead?" question. "It's scary stuff, but scarier when you realize it's the kind of information that credit-card companies and data aggregators are already selling, for pennies, to advertisers every day" (para. 5).

Apparently, no online behavior is off limits to marketers. While my university monitors all research for ethics, nothing keeps those tracking your Facebook or other apps from using data as they see fit. We are being watched. Closely.

The nearly complete adoption of mobile smart phones presents perhaps the most troubling aspect of the privacy question. Whether or not you check in or broadcast your location, telecommunication firms may collect continuous data on your whereabouts. And they do not have to tell us what they are doing with the data.

Way back in 2000, MSNBC framed the question differently. Brock Meeks, asked: "Is privacy possible in the digital age?" The subtitle for that piece was a harbinger: "If it isn't dead, then it's hanging on by a thread." Yet, Meeks' predicted "privacy rebellion" against digital data users "free to rape and pillage our personal information" (para. 26) has yet to happen.

Could it be that we really don't care? Is privacy dead, really?

Desperate for another answer, I took the question to AEJMC Law Division members. Some are attorneys, and others are not. The cautious answer was not far from Brock Meeks' "hanging on by a thread" response. One must ask what we mean by privacy. T. Barton Carter, Boston University chair and professor, said of the technologists and their privacy is dead mantra: "Clearly, for them, they want it to be dead." From facial recognition to GPS, Carter said "it makes the problem shift" with changing behavioral norms.

Legal precedent on the various aspects of privacy, such as "intentional infliction of emotional distress" claims being driven by reality television, is now being established not through journalism cases. Rather, the lawyers observe, there are really bad disclosures on TV and social networks -- cases in which judges have found limited privacy rights. Time will tell how the Supreme Court will define privacy beyond the Fourth Amendment government search and seizure law.

Blogger Raymond Wacks notes that European safeguards, such as those from the Council of Europe Privacy Convention, go beyond our centuries old common and constitutional law protection. In his view, "The United States lags far behind the more than fifty countries with comprehensive data protection legislation" (para. 12).

The Bismark Tribune's Keith Darnay last year did a fairly exhaustive look at law review and other commentary and remained concerned about our lack of privacy protection. Darnay quoted Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg's statement that the norm of privacy gave way to the sharing culture that his social network site enables.

Still, some of us -- even fans of Facebook -- keep asking the question: "Is privacy dead?"

I'm not ready to pronounce privacy dead. Zuckerberg is right that norms evolve. But we may not be finished with the norm of privacy. From journalistic access, to social media behavior and big data uses, we're just beginning to understand the death of privacy as a problem. After all, many have noted that by clicking any article (including this one), you've just been tracked.

Back in February President Obama suggested the need for a "Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights." The principles of the proposal included consumer control of data use, transparency, security, access and accuracy.

I don't expect these to be the stuff of presidential debates this year. Which politicians are independent enough to take on the corporate giants and the political lobbying machine? If privacy is hanging on by a thread, it will take a Spiderman to weave the next generation of protection.