David Humphrey is voracious. The relentless artist is on an endless quest for imagery, high and low, and for sensation, strange and familiar. His curiosity shows in his paintings--he easily references Eisenhower and naughty cats, de Kooning and bestiality. It's no place for the timid, but somehow it all comes together in work that is wicked and fantastic at the same time. Humphrey, who shows at Sikkema Jenkins in Chelsea, is on a run: he has an exhibition at Lux Art Institute in Encinitas, CA, and just curated a winning show at Galerie Zürcher on Bleecker Street. Last year he published a collection of his writing, Blind Handshake (Periscope), won the Rome Prize, and still makes time to teach at Yale and Penn. When you stop to think about it you realize what's what: He's an intrepid artist of our time.

We spoke recently at his Chelsea studio.

Humphrey in a rare moment of inaction.

You're going to California tomorrow for a new show.

I go to the Lux Institute, in Encinitas, north of San Diego, and they're doing a pocket survey exhibition with a residency built in. So I've got to be there, making new things, augmenting the show. I'm planning to vandalize the show. It opens when I arrive, and then I have this time to mess with it.

How do you approach setting up a show like that, curating your own little retrospective

I would like to have curated my own retrospective, but I also enjoy letting someone else do it, and in this case they did it. So they're telling a story about me, which gives me freedom to play around with it. It's a fiction that's cooked up for some purpose, and I'm always interested in ways of unraveling those purposes. I like looking at older work, many of the things here in my studio are kind of collaborations with an earlier self, so sometimes I'll modify old things.

And what was the theme the curators came up with?

There's no title to the show, but one of the things that emerged to me, was the exploration of inter-subjectivity, stories about what happens between people, and using different painting languages as stand-ins for different individuals.

Proud Owner, 2007, Acrylic on Canvas, 108 x 44".

You're interested in different types of painting language, whether it's abstract expressionist or Japanese animation. How do you view different types of painting language and how you can combine them within one canvas?

Well it's a little bit like an internal theater. I like the idea that I can operate out of an incoherent, overpopulated self. I can split off those parts, allow them to exercise themselves in different idioms, and that the painting itself is a kind of theater of those selves.

So Dwight Eisenhower could inhabit the same place as a misbehaving cat--different things come together, real and imagined.

In the case of Eisenhower I would copy his paintings, in a pretty devotional way, and I could spend time with the great man, and then step back and interact with this new him, this internalized him and basically fuck with him.

Can you talk about how you got interested in that?

Well I rolled into an interest in him as a result of my interest in amateur painting. I think that amateur painting is really exciting because it has a body of flaws and a wounded-ness and beauty underwritten by its failed ambitions. You can see that somebody was trying to do something, copy a photograph, show the beauty of their child, and the child comes out kind of awkward and strange and funny. I thought it was, in a way, the route out of postmodern painting, which in its rubbing of different languages against each other implied a role of the artist as the critical, detached knower. I preferred a more robust and subjectively entangled artist.

What Steve Saw, 2010, Acrylic on Canvas, 72 x 60".

Did you react against what he did or did that become a field for you to carry out other concerns of yours?

There's something about the super specificity of his decisions: This tree here, this little barn over there. It seemed really eccentric and strange as I spent time with him. At the same time there was a greeting card utopianism that I thought was really odd coming from this soldier, supreme allied commander, overseer of the Cold War.

You draw from the figure regularly, can you talk about how the figure works in your work?

I got pulled into drawing from the figure again, through these sessions with Will Cotton. He would bring a group of friends in, there would be a model, and we all drew. It became a way to go to the gym, the depiction gym, and get stronger, but also to figure out a way to craft this cognitive motor-perceptual challenge into something that had life in it, that was art. It took me by surprise as something that I really liked. It's an independent side practice, but this idea of just going into the state of looking, and trying to translate that into some kind of tactile representation, or a representation through the language of touch, seems really interesting.

You have a recurring catalog of images you like to use. How do you collect characters, whether they're naughty animals or war heroes?

I gather them and I try to get to know them. There's the endless search for protagonists. So, in a hunting gathering way I go through pictures, magazines, other peoples' art, with an eye to working its way into my pictures. I'll test them out, I'll do screen tests with drawing, and see if the image has the capacity to grow, to adapt, and then I'll try them in a different context.

When it passes a screen test, is it because it's iconic or strange?

It's really hard to describe, it's some set of ratios of otherness, strangeness, and connectedness that have to all coexist. If it stays alive as an unanswered question I will keep developing it. I've got a body of work that has to do with interspecies relations, and part of it came out of being in Rome, and looking at a lot of images of predation, of big cats and their prey. Later on in the Christian era, Christians get thrown to the big animals. It's this spectacle of predation. So I did a lot of paintings thinking about predation in terms of inter-subjectivity, like relationship dramas. They're kind of sexy, you think of Hercules and the lion, they're wrestling, entangled, and mutually defining there's a reciprocity.

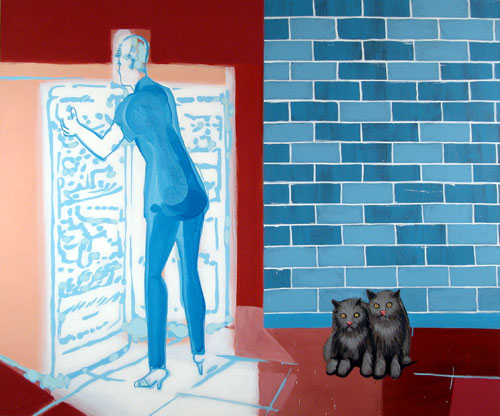

Fridge, 2002, Acrylic on Canvas, 60 x 72".

Can you talk about your interest in abstraction?

In some paintings abstraction is like the pathetic fallacy. It's the weather infused with feelings. I like having that be the ground, the place into which these characters advance, move, exit, whatever they're doing, rather than having the subjectivity be monopolized by the characters.

But then there's also the history of the marks, we recognize a late de Kooning or something specific.

I don't think the main subject of these is sort of a meta-historic commentary. I don't think I'm addressing those earlier paintings as manifest subject. But, the fact that they come with an associative cargo, a sense of time and memory, is something I embrace. All those layers of content, I hope, infuse and inflect the more psychological drama that's being presented. Also it's a thrill, I love late de Kooning, and I've never really attempted to work in a way in which the scale of the body, of the movement of an arm across a certain distance, has had a role. I wanted to see if I could get that to make sense. A lot of what I do is driven by the question 'What if?' 'What if this was with that?' And then, I try it out, test it, and see if it has the power to develop.

Kitties on the Wall, 2005, Acrylic on Canvas 60 x 72".

It's funny you saying that about what the feeling of making a mark is like, because Dexter Dalwood makes paintings in the style of a certain artist, and he said painting like de Kooning is the most intense. He couldn't believe the physical energy that it took day after day.

There's a sense of the ghost of the body that made the thing, that haunts de Kooning and so much gestural painting. I'm interested in that fiction, the fiction that is produced by the mark, the fiction of someone having made it.

You say you ask 'What if?' You keep seeking new things out--now you've started to play the bass. You're a genuinely curious person.

I feel like my exercise of vitality, my creative instincts, it sounds really corny to say that, really come alive when I'm disoriented. So I put myself into situations in which I don't know quite what is going on, and that the adaptation, and the navigation, is the work.

The Lichtenstein show of black and white drawings was interesting because he was in the process of discovering the style that he mastered. But it's more interesting while he's coming to terms with his style then when he finally sorted it out. Not many artists keep themselves in an ongoing state of discovery.

There are definitely commercial forces that urge artists to be branded, to be easily recognized, and to have something that can be distinguished from all the other artists.

You just curated a show at Galerie Zürcher.

It's called In a Violet Distance, which says almost nothing about what the show is, it's a show of images of people looking at things, that tries to tangle looking with making, remembering, imagining. So each work is a different turn on that. Curating is a great way to organize thoughts, it's like theater, it's making a story with other peoples work, and treating them like characters. But it's like writing also, it's a multiperspective essay on whatever subject you've chosen.