Last week, when Michael Walker of Beckley, West Virginia, read in his local paper that high-potency heroin--or opioids sold as or cut with heroin--caused an outbreak of 27 overdoses in just four hours in the nearby city of Huntington, he thought of his 19-year-old son, Matthew, who has been off of opiates for three months, the longest he's been without the drug in years.

"I know it's early for Matthew, and what a struggle it still is," said Walker, 42, a white working-class dad. "A lot of people call this a problem, but it's an epidemic," he said, while describing the situation in West Virginia.

West Virginia ranks No. 1 in the nation for overdose fatalities. Pill mills churning out OxyContin addicted many in Walker's hometown, including his son. Once the dirty doctors were kicked out of town and the pill supply ran dry, Walker said his son turned to heroin. "You could walk down the street and knock on someone's door, and there heroin was," he said.

Situations like the one in West Virginia sound off the opioid epidemic siren. Both local and national news carry its echo across the country, citing each outbreak as the relentless continuation of an ongoing drug crisis--one that's described as having crept out of the so called inner-city and into affluent suburbs and rural towns, causing premature death en masse among the white population. Ask someone like Walker--middle-aged, working class, who is up on current events about opiates and heroin--and they'll tell you how dire things are.

But researchers at Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston, Texas, say government data do not reflect what the media and politicians have said about the magnitude of the epidemic.

The Baker Institute's newly released Brian C. Bennett Drug Charts use data collected by the University of Michigan's Monitoring The Future survey, along with the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, to chart drug-using trends over a span of 40 years. The charts deliver a bird's-eye view of drug use in America and a counter-narrative to the opioid epidemic.

Along with the charts--which we'll get to--Rice University released a policy brief written by William Martin and Katherine Neill, both doctoral fellows in drug policy at Rice. "These charts," they write, "caution against uncritically accepting alarming announcements of drug abuse epidemics by media, politicians, religious leaders, law enforcement agencies, drug treatment facilities, voluntary associations, or others with real or opportunistic reasons to sound the klaxon."

Brian C. Bennett is a former military intelligence analyst who uses data to destruct drug war rhetoric. For years, he's been a thorn in the side of many drug prohibitionists--mainly because his encyclopedic catalog of drug-using trends poke holes in what he calls prohibitionist fear-mongering. Like the time Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates, who founded the DARE drug education program, said that "casual drug users should be taken out and shot."

That would be a lot of people dead in the streets. Many people identify as regular drug users each year, and the number of people who call themselves a "frequent-user" remains stable, despite screams that drug use is on the rise.

In reference to cocaine users, which the LAPD targeted during the '80s crack epidemic, the authors of the policy brief write, "It is clear that not all use is abuse and that most people who get into trouble with the drug recover from it, many on their own without treatment, participation in a 12-step recovery program, or relapse." Rarely will you hear law enforcement speak of cocaine use in such plain terms. But that's what the data show.

The Fix reached out to Bennett to discuss his newly released charts, and how the numbers behind the opiate crisis paint a less frightening picture.

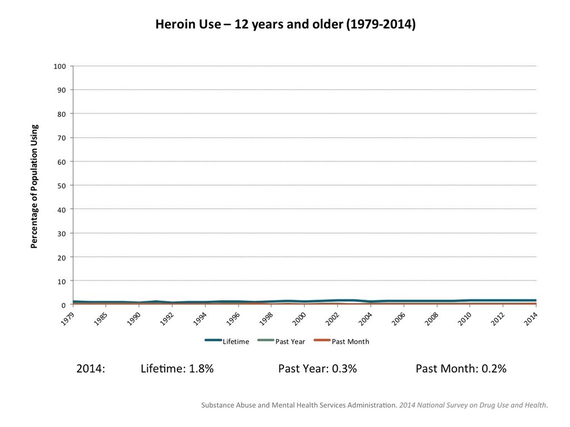

Bennett's charts appear counterintuitive if you've been watching the news. For instance, they show heroin use has remained stable between 1979 and 2014. Though there was a jump to 914,000 heroin users from 681,000 between 2013 and 2014, he asks his audience to keep in mind the size of the U.S. population ages 12 and older, which in 2014 was over 265 million.

Because the charts are scaled to the U.S. population at large, such fluctuations look like flat lines--"insignificant in the big picture," he said--when charted.

The same can be applied to painkillers like OxyContin, says Bennett. In 2014, the number of people who reported using painkillers for "nonmedical use" in the past month was 5.1 million. Martin and Neill, the authors of the policy brief, write, "This is not a small number of potentially problematic users, but it is a small segment of the U.S. population--1.6 percent of those age 12 and older."

Bennett told The Fix that, "When looking at pills, the past year use numbers have been declining a bit." But if you get your information from, say, the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, who wield a budget of $88.4 million dedicated solely to keeping kids off drugs, they'll tell you painkiller use is on the rise.

"There was a brief spike in the use of [painkillers] in the 2009 and 2010 estimates," said Bennett. But he adds that ad hoc reports exaggerate these upticks. "This helps illustrate an important point concerning reporting of these numbers: the tendency is to cherry pick the numbers to paint the worst possible picture. That is why it is so important to consider the complete data sets when discussing these issues."

Read the rest on The Fix!