You can take a class in college in abnormal psychology where you learn everything that is wrong with us as humans. What about everything that is right with us? And by right, I mean the ability to reach our full potential -- being the best we can possibly be, all the time. Why don't they teach classes about this in college?

Maybe there isn't enough knowledge about how to do this. Or perhaps the puzzle pieces are just starting to come together that link brain function to optimal functioning. Perhaps we don't yet know how to train our brains for optimal functioning (for more on this, watch a 10-minute TedX talk I just gave).

We certainly can think of extraordinary people -- those who seem to sail through life, performing effortlessly and having a great time along the way. Michael Jordan is a great example. With his tongue hanging out of his mouth, he consistently dominated his competitors, finishing as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, in the sport of basketball.

So how can we become the Michael Jordans of the world, no matter what our sport, profession or pastime? Maybe we actually can do this -- perhaps we can be great at whatever we do.

It may start with learning to get out of our own way. What do I mean by this? We can all remember times when we've tripped ourselves up or otherwise gotten in our own way simply by, well, getting in our own way.

Here's an example. Remember Lolo Jones, an American hurdler favored to win in the 2008 Beijing Olympics? What do you remember? She was at the 9th of 10 hurdles, in the lead. And then what happened? In an interview with Time magazine after the race, she said:

I was just in an amazing rhythm ... and then I knew at one point I was winning the race. It wasn't like, Oh, I'm winning the Olympic gold medal. It just seemed like another race. And then there was a point after that where ... I was telling myself to make sure my legs were snapping out. So I overtried. That's when I hit the hurdle.

She got in her own way. Instead of letting her body do what it had trained to do for years, to be perfect for this shining moment in history, she tripped herself up. Literally. She tripped on the ninth of 10 hurdles and finished seventh. Now this is an important point here. It wasn't that she was thinking -- she had plenty of thoughts. It was that she got caught up in them. As she said, "I overtried."

When we get caught up in self-referential thinking, we get in our own way. Are there other ways we do this?

My lab at Yale is researching better ways to help people quit smoking. What are cravings like? They feel great, right? Just remember the last time you really craved something you couldn't have. That extra scoop of ice cream when you were on a diet, that car that was just out of your price range. That cigarette when you were trying to quit. What does this really feel like? We get all squirmy and restless; we break out in a sweat. This isn't great -- it sucks! I had a patient tell me that his cravings were so strong, he felt like his head would explode if he didn't smoke.

Lolo got in her own way by getting caught up in thinking, just as these folks get in their own way by getting caught up in or resisting their own cravings. See the theme here? Getting caught up or pushing something away.

So we taught smokers mindfulness -- how to stay present and to fully be with cravings instead of trying to distract themselves or resist the urge to smoke. We taught these folks to get out of their own way -- to learn that they could let their cravings come up, do their dance and go away without getting sucked into them or needing to push them away. Their heads didn't explode, and they stopped smoking. In fact, in a randomized controlled trial, our training ended up being twice as good as the gold standard. Just by helping people to get out of their own way.

This was great to find -- a simple (but not easy!) practice like mindfulness can help us get out of our own way, and has demonstrable effects on habits that are tough to change, like smoking.

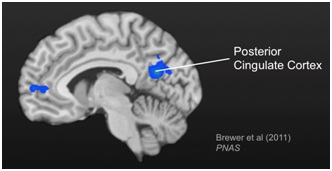

So what is going on in our brain when we're being mindful? To answer this, we brought experienced meditators into our fMRI scanner and had them simply meditate while we were measuring their brain activity. We found that across three different types of meditation, they were quieting down a brain region called the posterior cingulate cortex. This was interesting, because this is the same region that gets activated during states of craving, anxiety, rumination, and even when we are thinking about ourselves -- getting in our own way!

Now, there has been a lot published about meditation and the brain. So why should we or anyone else believe our findings? To confirm our results, we started using a relatively new technique called real-time fMRI neurofeedback. With this, when people are meditating, we can take a particular brain region and show people a visual display of how active it is in real time.

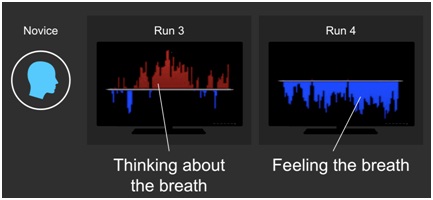

When we tested this with novice and experienced meditators, we found that their experience lined up well with their brain activity -- the posterior cingulate became active when folks were caught up in thought and quieted down when they were meditating. AND, some novices were learning from this, even though we weren't telling them to. For example, one novice learned the difference between thinking about his breath (run 3 in the figure), and feeling the physical sensation of it (run 4 in the figure) -- in just nine minutes! After the fourth run he said, "I was focused more on the physical sensation instead of thinking in and out." Notice how this lined up with a big shift in his brain activity between the two runs.

This seemingly rookie mistake can sometimes take years to fully understand, because we are all so used to living in our heads and thinking about everything, rather than just being with our lived experience (hence mindfulness is described as an "embodied" practice).

This is an important step forward, because it not only supports the idea that there are certain brain regions that can be markers of meditation, but also that we can start to use this information to develop tools to help people practice meditation. If we can track it, we can train it.

Like a yoga instructor or a mirror that gives us feedback when we are practicing our yoga poses, perhaps in the not-too-distant future, we will have "brain mirrors" that can give us feedback about what specific regions of our brains are doing, such as when we are meditating. Current EEG neurofeedback devices only show us surface scalp electrical activity (not quite the mirror into our brain that we want).

While we wait for accurate neurofeedback devices to become readily available, we can still use our own awareness for feedback to see how much we are getting in our own way. Like Lolo showed us, we can start paying attention to thinking: Are we getting caught up in thought vs. just noticing thoughts arise and choosing which ones to act on? Following our smokers' lead, can we notice what cravings feel like, and just be with them, instead of getting sucked in or pushing them away?

So, let's flip this on its head and say that our somewhat normal way of being -- getting in our own way -- is abnormal. In contrast, our optimal psychology is one where we're fully engaged in life -- effortless, joyful, and as a result extremely productive. And as our neuroscience advances, we can build tools to help all of us move into this optimal state more and more. Hopefully soon, instead of focusing on abnormal psychology, colleges can start adding new courses on "optimal" psychology.

Watch the whole Tedx talk here.

For more by Dr. Judson Brewer, click here.

Dr. Brewer's lab website.

References:

1.Brewer, J.A., S. Mallik, T.A. Babuscio, C. Nich, H.E. Johnson, C.M. Deleone, C.A. Minnix-Cotton, S.A. Byrne, H. Kober, A.J. Weinstein, K.M. Carroll, and B.J. Rounsaville, Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2011. 119(1-2): p. 72-80.

2.Brewer, J.A., P.D. Worhunsky, J.R. Gray, Y.Y. Tang, J. Weber, and H. Kober, Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011. 108(50): p. 20254-9.

3.Garrison, K.A., D. Scheinost, P.D. Worhunsky, H.M. Elwafi, T.A. Thornhill, E. Thompson, C.D. Saron, G. Desbordes, H. Kober, M. Hampson, J.R. Gray, R.T. Constable, X. Papademetris, and J.A. Brewer, Real-time fMRI links subjective experience with brain activity during focused attention. Neuroimage, 2013. in press.