For those who worry that the age of American exceptionalism is over, while the Greatest Generation sits laughing at us from the bar at their local American Legion post, the past week has certainly given reason to stand up and be proud. But, although good reason, it's not the daring raid of SEAL Team 6 that finally got Osama that I'm referring to (which in its execution was very cinematic, even down to the helicopter failure -- why does that always happen in reel and real life?). Rather, it is the reaffirmation that we make and export something that no other country can, and while our fathers and grandfathers in WWII may have saved the world from tyranny, we are conquering it with our product. And it's not our fighter jets, predator drones or advanced weapons system. It's something even bigger.

It's Fast Five.

The number one motion picture in the world, with almost $250 million in worldwide box office gross in two weeks. Don't you know, we rule -- what other country can do that? The Rock and Vin Diesel on screen at the same time (see, they're not the same guy) with lots of guns and more horsepower than at Churchill Downs. And Gal Gadot. Hello. This movie is so big, even Joaquin de Almeida got a promotion to boss, having formerly worked for the Columbian cartel (but the added stress of life at the top has caused him to put on a few since he went cabeza a cabeza with Harrison Ford).

According to Deadline.com, "Fast Five is Universal's biggest opening day ever in Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Netherlands, Malaysia and Thailand. It is the biggest opening day of all time in the United Arab Emirates." And there's plenty more countries to dominate. The second weekend's box office in the United States would have been even bigger if the picture hadn't been chased out of IMAX and large-format screens by Thor and his hammer. Don't worry about whether the movie made sense -- that safe got to Rio how? By UPS? And only to be dragged around town by two Chrysler Hemi's? Whatever. The target audience loved it. And that target audience is US.

Some would argue that aviation and armaments are our most important export, generating far more value than selling motion pictures and providing a key tool in influencing foreign governments. While manufacturing fighter jets and all that other high-end weaponry does employ a lot of people and earn us a lot of foreign exchange, including the spare parts and maintenance that goes with all those complicated weapons, the product itself is not particularly unique. Many countries make really popular weapons: France makes the Mirage jet; Israel the Uzi; and then, there's the most popular weapon of all time, the Kalashnikov. But taken together, they're not as deadly as Vin and the Rock together.

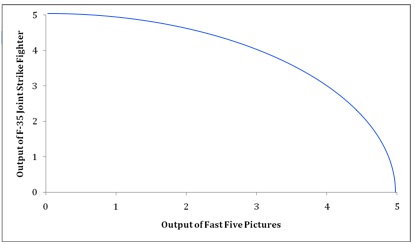

However, when you look at the numbers, there is a striking similarity in the product. The long-in-development F-35 Joint Strike Fighter by Lockheed Martin is projected to cost somewhere around $150-200 million for each aircraft, depending on whether you include R&D, overhead and maintenance. And the cost of Fast Five is somewhere between $125 and 200 million depending on who you believe and whether you include tax incentives and overhead. As the chart of production possibilities below shows, this similarity gets us to the classic economic issue of resource allocation: guns versus buttered popcorn.

In a world of scare resources, there is an opportunity cost for each investment decision, and for each sequel Universal Studios makes to Fast Five it means one less F-35. But then again, scarcity of resources and opportunity cost is not something necessarily in evidence for either the U.S. government or U.S. studio-financed tentpole movies. Back in 1776, Adam Smith had an answer for the rationale behind what gets produced, how and for whom. It was called "the Invisible Hand." The same theory explains how many of the big studio movies get green-lit.

But, maybe there's a larger significance to the connection between the comparative advantage, as Ricardo would say, that we have with our big action movies and our foreign policy. Commentators have noted the foreshadowing of the recent raid on Osama in movies such as The Siege. So maybe we really don't need to be so quick to send our young men and women into harm's way in order to further some murky foreign policy agenda that no one really supports. In the future, we can try it out on screen and if it plays in Peshawar, only then try it for real. Or send in Jack Bauer.

We've always used real-life events as the basis for movies; now the reverse is true. Perhaps we can avoid the billions of dollars that real war costs and just do it on screen for a few hundred million in production and marketing costs. Nobody gets hurt, and everybody gets a cupholder. Or maybe it works on premium VOD in the comfort of our homes.

And, if Vin and his crew become too expensive in sequels, we can always ask Stallone to get his band of Expendables back together. He's been there, done that. Ready, willing and winning.