I recently went to see the new film The King's Speech. Despite the improbable subject matter, an English king from a bygone era struggling to overcome a speech impediment, the movie appears to have touched the hearts of middle-America. Personally I was very moved by the film and the true story it portrays. It's British filmmaking at its best.

And yet notwithstanding my enjoyment of the film, I found Colin Firth's performance as King George VI difficult to watch. Not because it was anything less than very fine acting indeed, but because it reminded me of many childhood days spent sitting across the kitchen table from my father, waiting patiently as he, like his monarch, wrestled with an often paralysing stutter.

To have something to say and not be able to say it can only be excruciating, and yet it is something that an estimated 65 million people worldwide have to deal with every day of their lives. It's little consolation to know that kings can suffer as much as commoners, or that some notable orators, including Winston Churchill and movie stars such as Bruce Willis and Emily Blunt have had the same problem. If you stutter, life is different for you. Simple things that the rest of us take for granted, like telling a joke or addressing a group at work, giving a speech at your child's wedding, become potential minefields of embarrassment. No wonder my father had a short fuse. For him daily dialogue was an ordeal... frustration was a way of life.

With any other condition one would have expected that treatment would have been sought, diagnoses made and preventive options discussed, but in the 1950s and 1960s, stutterers suffered in silence. My father's stutter was never discussed. We became accustomed to it and tried not to think of it as anything unusual. Some days it was negligible and I would entertain a ray of hope that perhaps it was merely a passing thing... something he might grow out of. Then the next day it would be back, and worse. Simple statements blocked up in his mouth. One of us might unwittingly make things worse by hurrying him into what we thought he wanted to say.

I don't mean to paint a portrait of unalloyed gloom. My father was liked by his friends and colleagues and was considered something of a character. We had happy holidays together and Christmases enjoyed by all, except when we gathered round the wireless radio to hear the King read his annual Yuletide message -- his obvious difficulty seeming embarrassingly close to home. But by and large there was less relaxation in my father's life than there should have been. Jimmy Stewart dealt with his stutter openly and elegantly -- it became a charming part of his persona. In my father's case it was just an impediment, provoking bouts of self-directed anger that spilled out onto those close to him.

A few years after my father died, John Cleese, who had known him, told me he was writing a new film in which one member of a desperately dysfunctional gang of crooks had a stutter. He asked if I could help him understand how a stutter worked and where it came from. So "Ken Pile", with his bad haircut and rudely tight trousers, was born. Despite murdering dogs when he was supposed to be murdering their owners, Ken was the most sympathetic member of the gang, and though bullied because of his stutter, he rose up against his tormentor and squashed him with a steam-roller.

One of the by-products of the film's success was something that never happened when my father was alive. People began to talk about stuttering. Some stutterers thought Ken's character was merely cruel, others were quite tickled that a stutterer figured so prominently in such a widely-loved film. And that he had a chance to wreak such dramatic revenge on those who had mocked his affliction. But it was another four years before the most unexpected legacy of A Fish Called Wanda came to pass.

I was contacted by a man called Travers Reid. A successful businessman and a very funny, warm and delightful man. He had a stutter. He introduced me to Lena Rustin, a tiny power-house of a woman who was also an experienced speech therapist. They asked if I would support the establishment of a clinic in London for the specific treatment of stuttering in children.

My father's silent suffering came immediately to mind. Here was just the sort of thing that might have changed his life. A therapy that aimed to identify a stutter from the first moment it manifests itself, which can be as early as three years old. I agreed, and five years after "Ken Pile" first stuttered in A Fish Called Wanda, the Michael Palin Centre for Stammering Children opened in the Finsbury Health Centre in Central London. We had one full-time and one part-time therapist. And there was nowhere else quite like it in Britain.

Nearly eighteen years later the Centre has ten full-time therapists, has changed the lives of many hundreds of children for the better, and in 2008 was given a half a million dollar vote of confidence by the UK government, to extend the expertise of the London Centre across the country. Discussions are now underway to create something similar in the north of England.

There is nothing I am more proud of in my life than the establishment and success of the Michael Palin Centre, though all the really hard work has been done by others. A team of highly competent, wonderfully patient, extraordinarily devoted therapists have been supported by the very best management and the generosity of many fund-raisers. The invaluable political clout of a senior government cabinet member with his own experience of stuttering, led to the securing of unprecedented government backing for the work of the Centre. From the USA, the Stuttering Foundation and its President, Jane Fraser, have given us their magnificent support to continue and expand our work.

At the core of Lena Rustin's therapy is the involvement of the family. Without their participation the stuttering child feels isolated and it is only with their participation that it is possible to fully understand where and how the stutter has arisen and can be treated. To meet the parents who have come to the Centre and to see hope where there was once only fear and anxiety is both deeply moving and greatly encouraging. And to sit in on therapy sessions and see groups of bright, clever, funny children sitting together to discuss their own experiences of stuttering is inspiring.

The success of the Michael Palin Centre in London is of course only a small part of the work still to be done worldwide in helping those who stutter and we must never think that this particular battle is won. It has been estimated that one in every hundred people suffers from a stutter at some time in their life. This affects over 600,000 people in my home country and approximately 3 million sufferers in the USA. The demand for therapy and care far outstrips supply. Schools and workplaces need to know far more about how to recognize the problems of stuttering, and all children and parents affected by this cruel affliction deserve the benefit of access to a center like the one we have in London.

The cause for real hope and celebration is that attitudes have changed. Stuttering and all the problems that go with it need no longer be suffered in silence. Today there is every possibility that the lives of stutterers need not be forever blighted, as my father's life was, by the fear of failing to speak. Fifty years ago stuttering meant tight, tense, evenings around the kitchen table. It was a painful embarrassment and something that was, quite literally, left unspoken. Now, thanks to a powerful film, the topic is on everyone's lips.

It is inspiring to think of some of the prominent actors and singers of today who have conquered the affliction of stuttering. Many of those who have received the accolade of an Academy Award ® nomination or victory in recent years were once struggling to be heard. Before they found their voices, Nicole Kidman, Julia Roberts, James Earl Jones, Harvey Keitel, Eric Roberts, Samuel L. Jackson, Carly Simon and many more, had some of my father's problems.

If The King's Speech instills hope in those who suffer from stuttering and galvanizes the rest of us to do what we can to help, then it will have achieved something even more valuable than its deserved Oscar nominations.

How You Can Help

• Please support the non-profit Michael Palin Stammering Centre with a donation

• Learn more about The Michael Palin Centre for Stammering Children

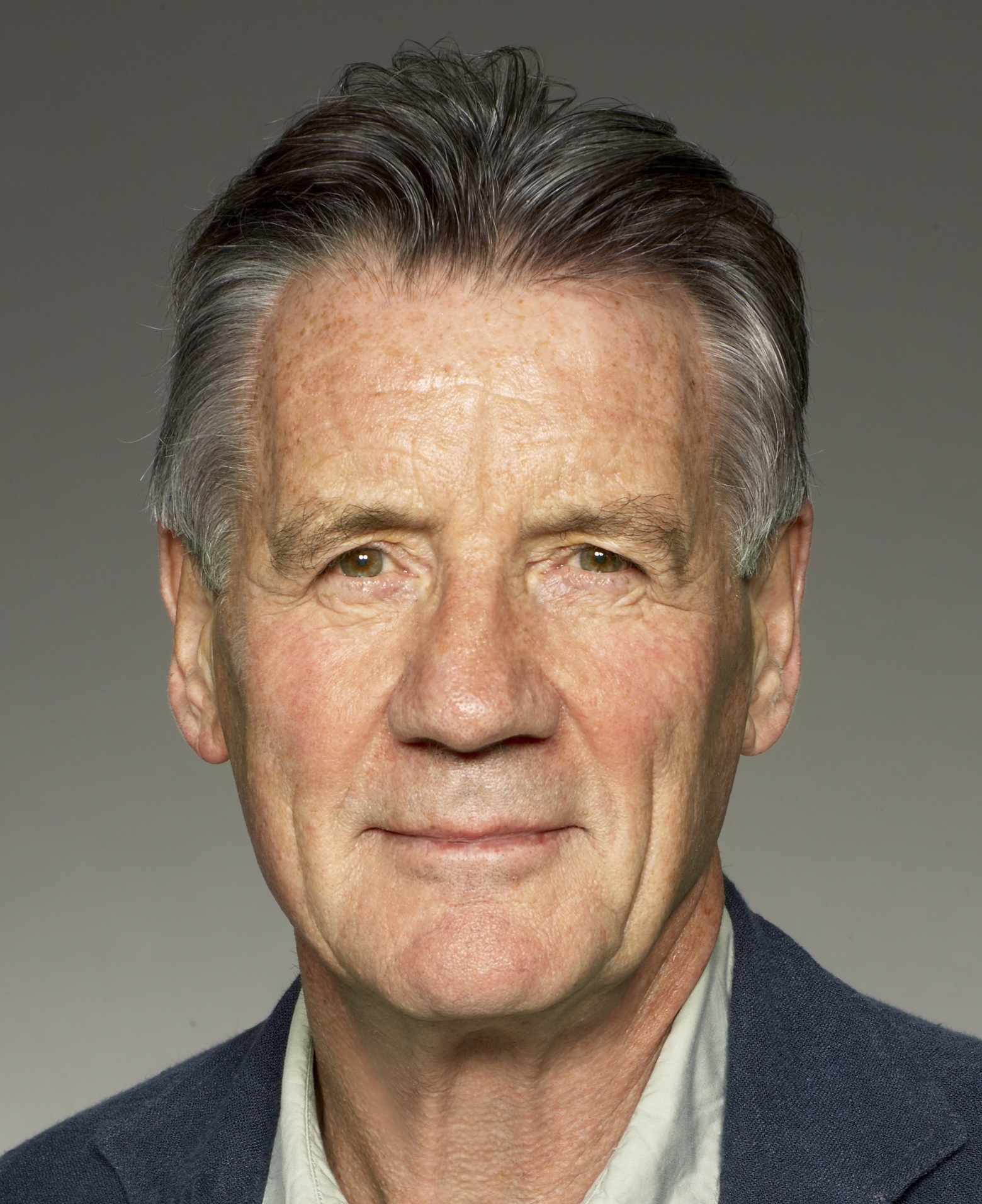

This essay has been provided to the Huffington Post courtesy of Michael Palin and The Stuttering Foundation of America. In support of this important cause, an abridged version of this essay has been published by our friends at the Los Angeles Times.