For just a day, it looked like a liberal Russian's nightmare: the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) was proposing the removal of classic stories by Anton Chekhov, Alexander Kuprin and Ivan Bunin from the school curriculum, because they allegedly promoted "free love." "Free love," for those of you under 60, basically covers adultery, "hooking up," and serial monogamy ("You call it sin; we call it college.")

Naturally, there was an uproar. Some ironically suggested that the proposed ban should start with the lower grades, removing fairy tales that set a bad example. The writer Lyudmila Ulitskaya condemned the "yahoos" (мракобесы) who seem to be waging a non-stop campaign to bring back the Dark Ages.

And, to be perfectly honest, this is the sort of story that gives someone like me an illicit thrill, the sense of satisfaction that comes when an institution you distrust once again behaves like a parody of itself. Fortunately for the country (if not for my dark side), an ROC spokesman walked this one back the very next day. Case closed. There's nothing to see here.

Or is there?

Here is what actually happened: on March 14, Archpriest Artemy Vladimirov, a member of the Patriarch's Committee on the Family and the Defense of Mothers and Children, announced that Chekhov's "About Love," Kuprin's "The Lilac Bush," and Bunin's "The Caucasus" do not belong in the school curriculum, since they all "sing the praises of free love." Calling such works of literature a "landmine for our children," Vladimirov insisted that his Committee contact Russia's Department of Education to push for a change.

The next day, ROC Spokesman Vladimir Legoida told the press that this was Vladimirov's "personal opinion," and that the Church "has no plans to try to have any authors excluded from the school curriculum." In other words, people were overreacting to one man's opinion and acting as though it were policy.

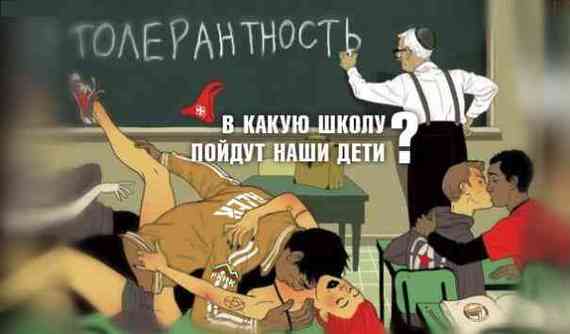

Legoida's words were perfectly reasonable, but they miss the point: how did the story get as big as it did? If we discount the usual blather about "Russophobes" in the liberal media, we need to consider why the story seemed credible. And that is because of Russia's local and central governments constantly putting out calls to ban this or that offensive phenomenon while decrying the pernicious influence of the Western Enemy and the Fifth Column on the country's impressionable youth. When you add in the growing influence of the Russian Orthodox Church in a country whose constitution proclaims the separation of church and state, nearly any call for a ban in order to protect public morality looks believable.

And, yes, this was just one person's word. But that one person is on a committee examining, among other things, education policy. And in the current political climate, we grow accustomed to seeing individual public statements by powerful people (or representatives of powerful institutions) as either a dog whistle or a trial balloon. Not to mention the fact that a call for this sort of ban had happened before.

When I posted the original story to Facebook, I was reminded that the high horse I'm riding might not have much ground to stand on. After all, school boards, churches, and parents groups throughout the United States repeatedly call for this or that book to be pulled from school libraries, and sometimes they are successful. Even Harry Potter is not safe from the wrath of small-minded American Muggles.

The difference, though, gets back to the power and scope of the individual statement. In the US, a successful book ban only affects a particular community or school district (though it is true that any pressure on Texas exerts an outsized influence on textbooks throughout the country). In a country with a centralized school curriculum, the result would cover the entire country.

In the end, one good thing probably came out of all this: teenagers throughout Russia are now likely much more interested in reading "About Love," "The Lilac Bush," and "The Caucasus," even if it's for all the wrong reasons.