An old black and white photograph came to mind recently when I had a moment to think about the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, ironically on a gridlocked highway that offers breathtaking views of the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

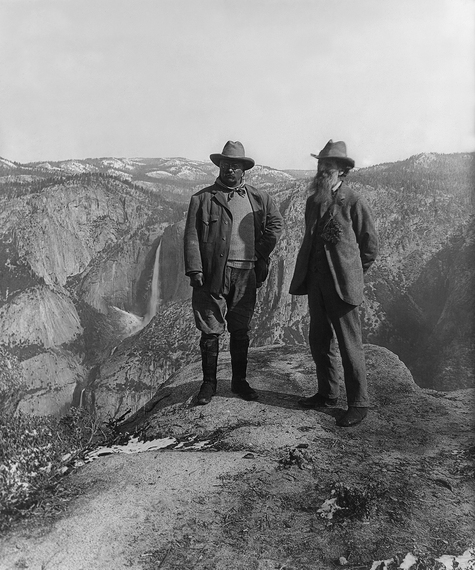

The photo is of Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir standing side by side atop Glacier Point, at what would become part of Yosemite National Park. It captures a great moment in our country's environmental history and perfectly illustrates the growing desire and momentum at the time to protect our natural wonders before the pressures of a developing nation gobbled them up.

In 1903, Muir took the president on a camping trip to Yosemite Valley in California to persuade him to place the area under federal protection. Three years after the photo was taken at this stone perch that provides a stunning overlook of Yosemite Valley and Yosemite Falls, Roosevelt did just that and signed the Antiquities Act. The Act resulted in the permanent protection of many majestic places, including the Grand Canyon in Arizona and Mount Olympus in Washington.

Roosevelt understood and truly felt the aesthetic power of wilderness.

"There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite, the groves of the giant sequoias and redwoods, the Canyon of the Colorado, the Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Three Tetons; and our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children's children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred," the president once said.

From Henry David Thoreau, to Muir, to Roosevelt, to Howard Zahniser, our country has been blessed by the ambitious vision of great people who fought and sacrificed their lives to ensure our land would be accessible to all, rather than purchased by an exclusive few. The actions of these pioneers -- and of many others -- helped secure large swaths of our country so that it will forever remain "untrammeled by man," as is succinctly written in the landmark Wilderness Act of 1964.

Nearly 110 million acres -- 2.7 percent of the total acreage in the lower 48 states -- are now permanently designated as Wilderness under the Act, which is the highest protection afforded to public lands. It disallows nearly every form of intrusive human encroachment to guarantee the landscape stays in its purest, untouched state.

Today, however, that momentum to safeguard our wild lands is apparently not of much concern to the current U.S. Congress when it is, without question, the most critical time to act in the history of our nation. Today's America is a far cry from Thoreau's Walden Pond. It is a nation less and less speckled by woodlands and day after day covered over with more pavement and money-driven enterprises as well as intense pressures to develop energy resources at home. We can never bring back our backyard Walden Ponds once they are changed or destroyed.

While this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, (Lyndon B. Johnson signed the historic act into law on September 3, 1964), it has been four years since Congress has chosen to employ it. A deepening divide in our already vitriolic legislative branch is certainly a contributing factor.

Numerous proposals to protect public lands are languishing on the Hill, including a bill by U.S. Senator Mark Udall of Colorado. His legislation would classify 22,000 acres along the Arkansas River in Colorado as a national monument and designate 10,500 acres of new wilderness in an area to be named Browns Canyon National Monument and Wilderness. The area defines Rocky Mountain beauty: 14,000-foot peaks and the Arkansas River meandering below through a rugged canyon of granite.

It is, indeed, one of many natural treasures deserving of protection.

Since 2012, my organization has fought hard for this proposal in collaboration with the Friends of Browns Canyon. We also worked with The Wilderness Society on the Our Mountains Matter campaign, which calls for the establishment of more than 1 million new acres of permanently protected federal lands in Colorado -- including Browns Canyon.

Clearly, Senator Udall understands the importance of wilderness protection.

"I strongly believe that we do not inherit the Earth from our parents -- we borrow it from our children. Wilderness, in Colorado and across the country, ensures these special places remain pristine for future generations to enjoy," Senator Udall wrote in an email.

Despite our efforts, this proposal and many others remain stuck on a long, and sadly growing, waiting list.

An overwhelming majority of Americans in the western U.S. support public land initiatives, according to the 2014 Colorado College State of the Rockies Project Conservation in the West Poll. Sixty-nine percent of Westerners are more likely to vote for a candidate who supports furthering public land protections, according to the January survey of 2,400 registered voters in six western states.

The 113th Congress has a choice: They can share in this long legacy of public lands protection or they can stand on the sidelines while President Obama establishes his. President Obama has already used the Antiquities Act to establish several national monuments across the U.S., much like Roosevelt did. Should Congress fail to act on these and other wilderness proposals, I encourage President Obama to use his executive authority under the Antiquities Act to immediately protect these areas.

My Colorado is much different than the Colorado of the early 20th century, when there were no gridlocked highways packed with millions of cars on traffic-choked interstates in eyesight of the snow-capped Rocky Mountains.

If the immense inspiration and momentum we once had to safeguard our country's treasures comes to a halt, we will regret it. There is no turning back the clock when it comes to wilderness.