There are two Presbyterian churches in my town, a stone's throw from each other. In a neoclassical temple on Nassau Street, Princeton's prosperous, mostly white middle-class parishioners gather to worship every Sunday. Down the hill on Witherspoon Street a more diverse group comes together to pray to the same god.

The day after the gruesome murders in Charleston, I walk to Witherspoon Presbyterian Church. In colonial days, this street was called African Lane. It was in the center of the historically black community, now slowly disappearing. It is a lovely wooden building with a slender white tower -- the mirror image of the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston. Across the street is the section of the Princeton cemetery where blacks were once buried apart from whites, while both awaited eternity.

A tall black man sees me looking at the church. He introduces himself as Eugene and says that he is one of the nine elders of the church. "May I come inside?" I ask. "Of course," he says taking out his keys and opening the door. Inside, it is strikingly simple - bare pews, simple stained glass windows, a wooden cross behind the altar. I sit in one of the pews and open a hymnal. It falls open to a well-worn page, Amazing Grace. I am not the first here to open to that hymn.

I ask Eugene what he knows about the atrocity in Charleston. "I have been to that church many times," he says. "It feels like my own family was killed there. I am from North Carolina, nearby. I heard Martin Luther King Jr. give a sermon there. I believe he has preached here at Witherspoon, too."

"Our church was founded in 1840," he continues. "So this year we are celebrating our 175th anniversary. Black believers wanted to give a response to slavery and contribute to equality of all people. This church was an important station on the underground railroad, the clandestine network of abolitionists who helped slaves escape to the North before and during the Civil War. "

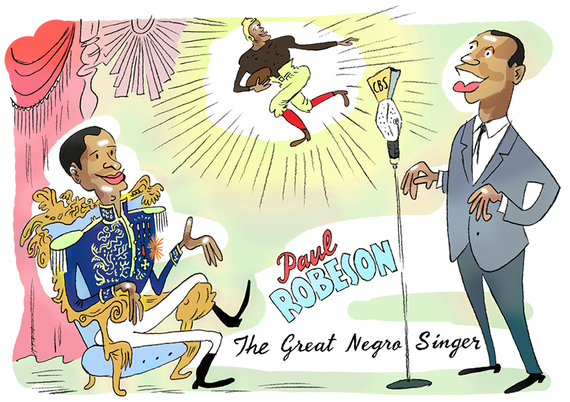

He points to a stained-glass window dedicated to William Drew Robeson. "One of our first ministers," he says. "Robeson escaped slavery in North Carolina in 1860 when he was 15. In the free state of Pennsylvania, he could study theology at a black seminary. Then he came up here. His youngest son, Paul Leroy Robeson, is one of my great heroes. Pastor William wanted to send Paul to Princeton University, but he was refused because of his color. So he played at Rutgers and became an all-American football player. He also had a wonderful, operatic singing voice and was a great actor. He was the first black performer of Othello on Broadway. "

I know Robeson for the old recordings of spirituals I listened to growing up in Holland: Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Go Down, Moses, Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen. Here he is best known for Ol 'Man River from the film version of the musical, Showboat. Robeson became a legend with this song that so heartbreakingly expresses the pain of slavery. The mighty but implacable, flowing Mississippi as a symbol of a world that sees great injustice but does not intervene. "He mus' know sumpin'. But he don't say nuthin'."

Robeson originally refused to sing the original incendiary version of the song because the hated n-word was in it. So Oscar Hammerstein and Jerome Kern then refashioned the lyric, first with "darkies," then with "colored folks," finally the more genteel, "we." ("We work all day, while the white folks play.") Later, Robeson's politically outspoken socialist views inflamed conservatives in the McCarthy hysteria of the 1950s, when he was blacklisted and his American passport was revoked.

As I leave the church, Eugene shakes my hand. "You're always welcome in our church," he says. "Our door is open to everyone."

I can't help thinking of the murdered black people in the church in Charleston. During their last prayer they welcomed the white killer, who said he almost gave up his horrific plan, because the people were so nice.

Paul Robeson died in 1976, sick and all but forgotten. It took until 2011 for the town of Princeton to put a plaque on the house where its most famous native son was born. As I walk away, I keep hearing his magnificient voice in my head: "Ah'm tired o 'livin'. An 'skeered o' dyin '. But ol 'man river, he jes' keeps rollin' along!"