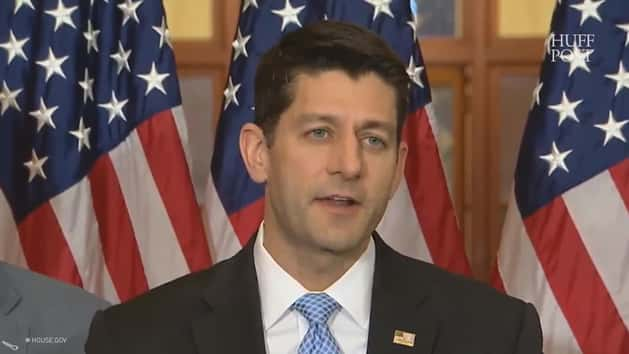

“An act of mercy.”

That was House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) on Tuesday, talking about the new Obamacare repeal bill ― a proposal that, according to an early estimate, could make up to 10 million people newly uninsured.

That estimate, from Standard & Poors, is crude and tentative. But future evaluations of the GOP proposal’s likely effects, including the official projection from the Congressional Budget Office, are likely to reach a similar conclusion.

Not that anybody should be surprised. The legislation would roll back the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid. It would also shift the law’s federal tax credits for insurance, so that the young and healthy get more relief, but the old and sick get less.

Donald Trump spent much of his campaign and early presidency promising “insurance for everybody.” Most Republicans have known better, and so they have made the argument that Ryan and his allies were repeating over and over again on Tuesday.

Forget about who has insurance, they say. What matters is access to health care ― and Republican plans will make it better.

Does access really matter more than coverage? Absolutely.

Would the Republican plan make access better? Almost certainly not.

The Affordable Care Act Made Access Better

The GOP argument here rests on two premises, neither of which holds up well to scrutiny.

The first is that the Affordable Care Act is a misnomer ― in other words, it doesn’t really provide “affordable care” ― because the newly insured on Medicaid can’t find doctors who will see them, and the ones with private coverage are stuck with high out-of-pocket costs that make even modest medical treatment prohibitively expensive.

Each argument represents one piece of the larger truth. The big problem with Medicaid, as even staunch defenders admit, is that the program pays doctors very little ― and, as a result, it can be difficult to get specialist appointments. The big problem with the Affordable Care Act’s private plans is that they tend to have high out-of-pocket costs, enough to keep even people with insurance from getting care they need.

But researchers who have followed the Affordable Care Act closely have found that, on the whole, access has clearly improved ― perhaps because critics exaggerate the extent of the problems, and perhaps because even imperfect Medicaid or Affordable Care Act plans are superior to having no insurance at all.

Here’s a quick rundown of the research:

People are less likely to struggle with medical bills, and more likely to have a regular source of care, according to a 2015 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association that’s one of the most comprehensive studies of the Affordable Care Act.

Six in 10 of the newly insured said their coverage enabled them to get care they could not get before, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund. The same survey found that people with Medicaid or private coverage through the health care law were able to find new doctors with roughly the same ease as those who had insurance already.

A slew of additional studies have reached similar conclusions. And all are consistent with two of the most thorough studies in the field ― one from Oregon and one from Massachusetts ― that found clear, solid evidence that giving people insurance improved their access to care and financial security. (The effects on health are more ambiguous, but that’s a story for another time.)

The GOP Repeal Bill Would Make Access Worse

The main argument Republicans make about their proposal ― the reason they say it will improve access ― is that it would “reduce costs.” At first blush, the argument seems plausible.

Republicans would weaken or eliminate the Affordable Care Act’s new regulations on insurance ― like the requirement to cover all people regardless of pre-existing conditions, or the minimum standard for generosity of coverage. When these regulations took effect, insurers raised premiums; if the regulations become weaker or go away, it stands to reason, insurers will reduce premiums.

But premiums would be falling because insurance would be covering less, so that medical care was becoming cheaper on the front end (when people paid premiums), but more expensive on the back end (when they actually used medical services).

At the same time, older people and those with lower incomes would be getting less financial assistance with premiums, and in some cases out-of-pocket costs, because of how the Republican proposal would redirect financial assistance from the federal government. Some of these people would buy skimpier plans, with greater out-of-pocket charges, because those would be the only premiums they could afford. Others would drop insurance altogether, with no protection from medical bills whatsoever.

Those are a lot of changes, and figuring out how they all go together isn’t simple. Fortunately, four researchers on health policy have done that work. In a series of articles they published at Vox, the experts (Harvard’s David Cutler, Covered California’s John Bertko, along with Topher Sprio and Emily Gee from the Center for American Progress) found that the net effect of the Republican repeal bill would be to raise costs for the average insurance enrollee by $1,542 per year in 2017, and by $2,409 in 2020.

“The Republican bill would cause millions of people to lose their coverage — but it would also increase costs significantly for those who remain insured,” the researchers wrote. Although it’s just one study, and fairly rough, it’s consistent with studies that found the Republican tax credit scheme would force older and poorer consumers to get far less assistance from the federal government ― which would mean either they’d have to pay a lot more to get a comprehensive policy, or make do with one that covered a lot less.

With the new repeal bill, Republicans have constructed legislation that would accomplish many of their most cherished goals, like reducing taxes on the wealthy and reducing the regulation of insurers. And their proposal would surely benefit some people, including some for whom the Affordable Care Act has meant higher premiums and weaker coverage.

But the net effect of repeal, even with a Republican alternative in place, is likely to be more exposure to medical bills ― and, as a result, worse access to medical care.

A lot of words to describe such a transformation come to mind. “Mercy” isn’t really one of them.