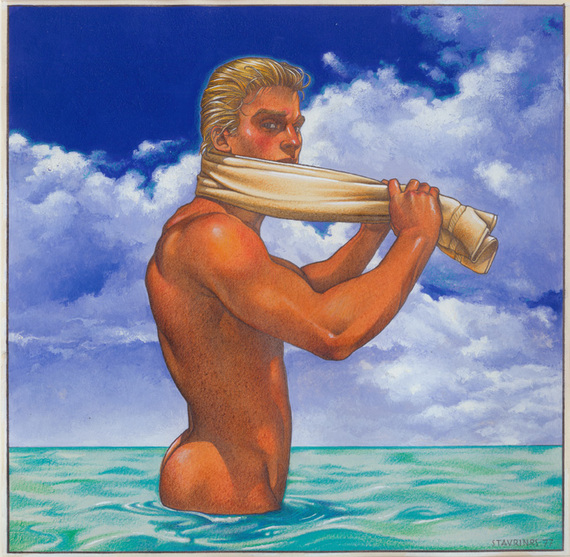

George Stravinos, The Bather, 1977, Pencil and gouache on paper, 10.25 x 10 in. Collection of Leo Paoletti.

There are three ways to look at the work in the new show at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art: "Stroke, from Under the Mattress to the Museum Walls," a show of gay erotic art, mostly drawings, during the "Golden Age of Gay Erotica," from the 1960s to the end of the 1980s (some might even include the 1990s) before the Internet basically killed the magazines that ran, and paid for, these pictures.

The first way is as drawings, the second is as erotica, and the third is as conveyances of coded messages during that time when queer life was coming to the surface but still covert enough to be a self-enclosed world that needed ways to talk to itself. The same way that Jews invented about six "private" languages to talk to each other during the Diaspora, gays had to do the same thing. And these drawings are certainly part of that.

I was very lucky that as a young writer in my twenties during the 1970s I worked for many of the magazines that employed these artists, such as the Mavety Media Group's Mandate, Honcho, Torso, and Inches. Blueboy when it was published in Miami as "The National Magazine About Men," and became known as "the gay Playboy," edited by Bruce Fitzgerald, a genius editor who pulled the gay men's skin magazine into an arena unheard of before, tackling serious social questions as well as seriously covering the arts; and Advocate Men, which again tried to bridge the space between serious literature-and-art and pure jerk-off material. So I had come into contact with some of these artists on a fairly firsthand level: they were illustrating stories by myself and other writers who were my friends. Mel Odom, a fantastic illustrator still alive and working, was a frequent contributor to Blueboy back then. He illustrated a piece I wrote called "Do Gays Have More Class?"

This was about 1978, and the question was: Did they? Mel's piece outlasted mine, and it's still seen in collections of his work. There was an attitude then that these magazines were in the know: they were conveying the big city smarts of New York, San Francisco, and L.A. to the rest of the country. Mavety who with his wife started Mavety Publications had a "nose" for hiring talented gay men to edit and run his magazines.

They included Sam Staggs, who went on to write entertaining books about movies (All About All About Eve: The Complete Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Bitchiest Film Ever Made!); Freeman Gunter who made a name for himself as a cabaret critic; and Stan Leventhal, a gay country singer turned novelist who hired other novelists to work with him. I used to describe these offices, filled with hard-working guys who could be openly gay in these protective environments, as "monasteries." There was a kind of sacredness to the calling; it took a lot of balls to say you worked for a queer magazine in those days, and there was a lot of brotherliness among us. I would go up to the offices at times simply to visit, have lunch, dish with my friends who worked there, and if I was lucky sell something or get an assignment.

What I did realize was the level of talent involved with gay erotica then. I'd felt that way about Tom of Finland (Touko Laaksonen) in the 1970s: that he was combining an almost casual level of Renaissance drawing technique with outrageous content--like he had virtually tossed off these drawings in a masterfully effortless way. I met Tom once about 1986, through my friend the wonderful editor at FirstHand magazine, Lou Thomas. Lou started Target Studios, one of the great gay men's photo studios for erotica. One of his friends and competitors was Jim French, an utterly talented draftsman and photographer who started Colt Studios. French's drawings were superb: he had a deft sophistication of line and shading that appeared almost shocking within the hypermasculinity he wanted to convey.

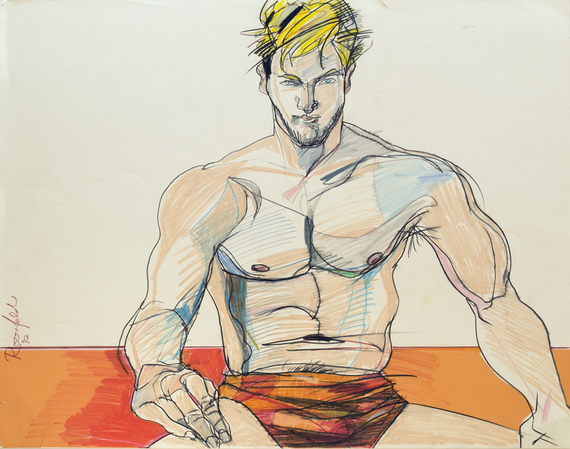

To be able to pull this off was in effect a transgressive act: people expected openly queer erotic art to be . . . well, kind of funky and amateurish. Here were these two artists who could, as Picasso said, "draw like Raphael," and yet convey a molten imagery. A third artist shown in "Stroke" is George Stavrinos. Stavrinos came from the world of nosebleed high fashion--he did a series of Barney's and Bergdorf's ads in the 1970s that were epochal: they were sophisticated, wry, and still amazingly middle-finger-in-your-face queer. I knew George through the circle of writers and photographers I hung around that included Felice Picano and Arthur Tress. Picano used Stavrinos's work on the cover of his first Seahorse Press book, The Deformity Lover. One of the things I admired about George's work was the off-center, never-quite-perfect physique of his models. They were real, despite George's superb technique that elevated them to a higher level of desire and perception. They were no demi-gods, just winsome young men whose bodies always had a less-than-perfect physique. George himself was like that; he was short, his head was a little too big. He was shy and sweet. I loved running into him when I did. He died in 1990, at the age of 42: another victim of the horrors of AIDS.

Two interesting ideas come through in this show. One is the fact that several of the artists came to queer erotica after a lot of classical training and commercial success either as fashion illustrators (an occupation that is now almost dodo extinct but which up to about the 1990s was a steady employer of artists) or fine artists. These include Antonio Lopez (who had worked for Karl Lagerfeld), the beautiful drawings of Richard Rosenfeld (who had worked for WWD and Vogue), James McMullan who did Lincoln Center Theater posters, and of course Odom and Stavrinos.

The other is simply about artists who bent their talent, that is shaped and worked it, because of their own intense desires and feelings. Sometimes this comes through as a little clunky, and other times it absolutely wipes you out. Like, how did Michael Breyette, who was basically self taught, have the finesse to produce the kind of images he did? His picture "Unsuitable," from 2009, looks like Jon Hamm as Don Draper, with one unmistakable exception exposing itself to us. The Swiss artist Oliver Frey, born in 1948, learned how to draw through 36 correspondence lessons from the Famous Artist School, of the back-of-matchbooks fame.

He has one fantasy-based piece in the show that is very strong, and real enough to transcend fantasy. Two of the artists, Domingo Stephen Orejudos, who went under the name "Etienne," and Quaintance (George Quaintance) go back to the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, as purveyors of the kind of art you used to see on the covers of drugstore paperbacks. These were the images that burnt through your eyelids if you were a young man feverishly hoping to find something about yourself back then. Quaintance and Etienne were both big on "cowboy" images, that is stuff that had nothing to do with Zane Gray and Frederick Remington, but with the kind of dreams gay men passed among themselves, the cowboy as furtive, transgressive lover. It was as if a young Monty Clift had climbed down off the screen from Red River and got into your bed. The cowboy, the hot cop, forbidden fun in the locker room: this was the age of "trade," of straight men offering you the power you did not have, and it comes through often in this show.

Stroke was curated by Robert W. Richards who also came out of fashion illustration and tarried in Mavety's stable and with Advocate Men. He has done a great job with this show; it is very much a part of the evolution of queer identity and information that is still, I am happy to say, going on.

The show runs until May 25 at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, 26 Wooster Street, (212 431-2608. www.leslielohman.org.

Perry Brass's latest book is Carnal Sacraments, A Historical Novel of the Future, Second Edition. He has published 17 books, and can be reached through his website www.perrybrass.com.