I have fallen in love in Birmingham, Alabama. Not something that I particularly thought would happen, but there's no other way to put it--because it is with a painting. I have to declare this right now: the Birmingham Museum of Art has one of the most important paintings by an American artist in this country. It's "The Barricade" by George Bellows, painted in 1918 as a series of four monumental canvases Bellows produced to protest the horrors of World War One.

Bellows painted solely from newspaper accounts of the German invasion of Belgium--he never went to Europe. He was a New York painter, part of the famous "ashcan" school, and he spent his time between the city at the turn of the twentieth century, and parts of New England where he turned out mysterious, almost metaphysically poetic landscapes surrounded by water and fog, and the people who worked on them.

As a younger man I never really thought much of Bellows--there was the famous "Stag at Sharkey's," one of the great, constantly anthologized boxing images that also easily comes across as rampantly homoerotic--but not a lot more. Then from November 2012 to February 2013 the Metropolitan Museum hosted a full banquet of Bellows' work with about a hundred paintings, drawings and lithographs. People went nuts over it. I did. Here was this incredibly brilliant, "dumb"--meaning powerfully wordless--overlooked artist who had produced in a short lifetime (he died in 1925 at the age of 47) this entire output of an inner life, a political life, a public life and a private life. His work is rife with eroticism and yet there is this strange turning away from desire; it is like he is searching for an expression that is even deeper than painting can convey--Dostoyevskian in its reach, in the depth of his work--and he's going to do this solely in an American, close to everyday idiom, with a brush and bunch of paint tubes.

The most amazing thing is that he comes close.

I was amazed; floored; moved to tears at moments. I had not had this feeling from painting in so long: that it gripped me so hard. Some of his paintings are simply nutty. Herds of naked street boys jumping into the Hudson. Craziness on parade in Central Park. Men at a gentleman's bathhouse.

Then suddenly . . . Zap! He reaches absolute Ground Zero of the brain at its depth--that point of no return rare in any art form where the real and the finally completely mystic meet: it's there in his landscapes on Mohegan Island, off the coast of Maine. Men exerting their muscles against the water. The gallant puniness of men approaching the awe-inflicting, infinite darkness of ocean.

A painting that ripped me apart was "An Island in the Sea." It is one of those paintings (and Bellows work is filled with this) that you have to see in the flesh. It has a Zen quality of complete apprehension: you don't "illustrate" reality. You produce it.

"An Island in the Sea" is not a picture of a brooding land mass. It is a brooding land mass that became a picture, like the foggy depth of an Alan Hovhaness symphony in oil. At the Met show, I didn't want to leave it. It opened up my brain like an act of exploration, where it remained there, someplace in my eyes. I have rarely had this experience with a work of art. It made so much other stuff look like bullshit.

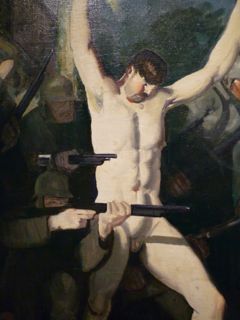

"The Barricade" was the orgasm of the Met show. I looked at it and had no idea how Bellows had produced this painting. It is not a realistic depiction of a historical event. It is simply Bellows' reaction to the Germans using a group of innocent Belgium villagers as "human shields" to advance their own progress. This is something that has become S.O.P. in contemporary terrorist-warfare but in Bellows' time it was a, well, a "novel" type of atrocity. Bellows portrays these hostages as naked--what is so penetrating is how real they are, portrayed so individually, and yet done with a casual vividness that pops each figure into the action of life. There is a cinematic spontaneity and movement to the figures and yet the design structure of it is flat like a mural, butting right up against the picture plane. There are ten naked figures in it, two of which are female, and one of which is a young boy of perhaps ten. Perpendicular to the figures are bayonets and the barrels of rifles. The dark gray uniforms of the "Huns" make the ghostly white, pathetically innocent flesh of the hostages stick out even more.

In the dead center of the painting is a muscular, almost stocky male with a developed chest and arms reaching out over his head in a pose of both a surrender and crucifixion. His head is down. In fact, none of the faces actually look directly at you with the exception of one bearded naked man who is like a Disciple, and whose gaze is directed up but very possibly could strike you. Bellows' genius had produced these raw skin colors that seem both unreal and yet super-real at the same time. Bellows was impressed with the famous Armory Show in New York in 1913 that included his work as a young American painter and also Picasso and Matisse. He started to incorporate Fauve colors in his own paintings, utilizing Matisse's technique of using pigment as if it were raw light itself. This is very evident in "The Barricade." The skin colors knock you over, and, again, as in own Matisse's work, it's hard to really see this painting in reproduction.

Reproduction merely flattens it; it doesn't reach you fully. But once actually wrapped in the presence of this painting, we're seeing here the skin of dreams; experiencing a true moment--a depth-charge swim in an underworld of flesh. There is also desire within the revulsion of cruelty here, and there is no way to deny it. That is what makes the painting so fixating: it draws you in and keeps you.

It is easy to imagine Bellows in his time and period knowing this: being a part of America's aristocracy of creativity--he was a successful artist--within a society of provincial American, Anglo-Saxon-Puritan repression, alternating with genuine, unabashed, New York backstreet earthiness. This was a world of D. H. Lawrence's simmering desires straining to come out; Lawrence would soon be in residence as Mabel Dodge's guest in Santa Fe, New Mexico--and Bellows was feasting on its grittiness. Its forbidden flavors and bad-boy delights.

By the time Bellows died, a lot of America's innocence had gone. Prohibition arrived, and with it a release of vices never before seen in the U.S. His own pictures would have moments of vogue, and then be relegated to the usual encyclopedic view of American art history. You had to get through Bellows to get to the good stuff. Painters like Edward Hopper who could capture the mute depressive loneliness of urban America, came in. Bellows who could be sometimes "naughty," was now just quaint.

Until that show at the Met, which had actually started at the National Gallery in Washington, and which was such a revelation. When I saw "The Barricade," my first question was: how did this important, major painting get to Birmingham, Alabama? I tabled that, until I went to Birmingham last spring and made a trip to the Birmingham Museum of Art and saw that it is truly a marvelous regional museum with a beautiful selection of art that includes three John Singer Sargents (with a drop-dead Sargent society portrait of "Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d'Abernon"--just what every smart American heiress wanted to become), a major Georgia O'Keefe, some very good contemporary art, and even a few twisty, sexually provocative images like Bouguereau's belle epoch picture of a flirty "Aurora."

But still: How did "The Barricade" get to Birmingham? I asked Graham Boettcher, the director of the museum, that question.

He told me that the painting was purchased by the museum in 1990 from H.V. Allison & Company, a New York gallery handling Bellows' estate (or in fact, actually, the estate of Bellows' wife Emma Story Bellows who died in 1959), with funds from the Harold and Regina Simon Fund (an endowment for the acquisition of important American art), the Friends of American Art (a support group for American art comprised of collectors and enthusiasts), Margaret Gresham Livingston (a trustee and former board chair of the BMA), and Crawford L. Taylor, Jr. (a collector of American art). The painting was what most dealers would refer to as a "museum picture," that is, because of its size and difficult subject matter, most private collectors would find it hard to live at home casually with it, so it was best suited for a museum.

"I am thrilled," Boettcher told me, "that our institution did not shy away from such a powerful image in favor of a 'safer' example of Bellows' work. In fact, because Bellows never hesitated to use art as a vehicle to express his social and political views, I think it is particularly well suited to Birmingham's permanent collection, where we have many works from the Civil Rights era in which artists use their medium to bring attention to the injustices of racial inequality and Jim Crow in the Deep South.

"It has become one of the 'anchors' of our American gallery, and I was delighted when it was included in the National Gallery of Art's recent George Bellows exhibition, which traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Royal Academy of Art in London."

Birmingham, called for its greenness "Tree City," is unfortunately like most Southern car cities, clogged with traffic. It is trying hard to climb out of its scarred past. A trip to the Birmingham Museum of Art (which by the way has an excellent restaurant) more than rewards you, simply to experience "The Barricade," one of the great paintings by an American artist, and then fall in love with it.

Like I did.

Perry Brass has published 19 books, and is the author of the bestseller The Manly Art of Seduction, How to Meet, Talk to, and Become Intimate with Anyone, and King of Angels, a gay, Southern Jewish coming-of-age novel set in Savannah, GA. His newest book is The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love, Your Guide to Life, Happiness, and Emotional and Sexual Fulfillment In a Closed-Down World. The Manly Art of Seduction is now available as an audio book through Audible.com.