Patience, ladies. Patience. What's another century or so?

Nearly 100 years ago feminist and nurse Margaret Sanger opened the nation's first birth control clinic. Set in a modest two-story building off Pitkin Avenue, at 46 Amboy Street in Brooklyn's crowded, working-class, immigrant section of Brownsville, it was an open challenge to the authorities. The building no longer exists. No plaque marks the site. But from Sanger's activism, the movement that today is represented by Planned Parenthood emerged. And as everyone (and especially women) know, a century later the fight for free reproductive choice that Margaret Sanger launched still grinds on.

.

.

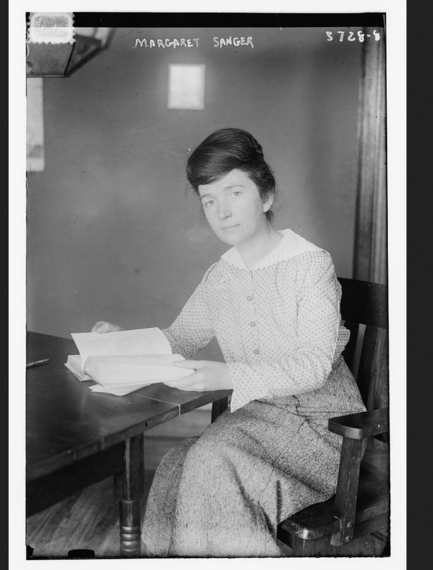

Margaret Higgins Sanger (1879-1966), American birth control activists, sex educator and nurse. Jan 20, 1916. Photo courtesy Bain News Service, Flickr Commons Project and Library of Congress.

"The poor suffer through ignorance - their own and the blind ignorance of man-made law. If I have violated the law and telling that woman how to prevent an eighth child - in giving the seven children a better chance to grow into useful citizens because of no further drag on the meager family income - do you blame me?" Margaret Sanger

Clinic Shut Down by Police after Nine Days in Operation

Sanger's Brownsville birth control clinic opened on October 16, 1916. World War I was raging. It would still be four years until women gained the right to vote in the United States.

The clinic lasted just nine days before the authorities shut it down. Sanger, who had already been jailed for her birth control education efforts, knew she was courting arrest.

The grounds? Obscenity.

Sanger and her colleagues were not handing out contraceptives or even written material. They were providing sex education and birth control information -- verbally, and to clients who came to the clinic of their own volition.

Sanger was indeed arrested. Irrepressibly, she said he'd use the opportunity to educate fellow women inmates about birth control.

Brooklyn Clinic Challenged Gag Laws about Contraceptive Information

In opening the Brooklyn clinic, Sanger set out to challenge the Victorian "Comstock law," a gag law named for politically powerful zealot Anthony Comstock. A moralist Moriarty, this man founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. The Comstock law categorized information about abortion, family planning, and contraception as "obscene" -- thereby disallowing its distribution by the US Postal Service and setting a precedent for suppression of birth control materials. (Read Margaret Sanger's stinging comments about censor Anthony Comstock.)

The Comstock Law reinforced what we today call "barriers to care." Hardest hit by this repressive morality code were poor families and women. It's a familiar litany: lack of education, low access to expertise, poor information, language barriers, limited personal resources, and legal and religious barriers from even learning about options for contraception.

Mothers unwilling to face another pregnancy or unable to support another child, resorted to back alley abortions, relied on charlatans, or used ineffective and often dangerous home remedies. The consequences could be, and often were, tragic.

Sanger also collected data to prove the need for contraceptive education. She sought to collect basic data on 1,000 women. They were asked sixteen questions, including the number of children, household income and pregnancy history, as a way, she said perhaps over-optimistically, to prove to legislators the logical, humane, reasonable need for birth control education.

Testing the Demand: Did Poor Women Want Information on Birth Control?

"She kept arguing that Catholic and Jewish immigrant women, and poor white women would come, but until she did opened that clinic, she didn't know," Dr. Esther Katz, historian and director and editor of The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at NYU said in a phone interview. (NYU, along with Smith College and the Library of Congress, has a large collection of Sanger's papers and letters.)

And come they did. Brooklyn was a diverse borough, with a large immigrant population and people of every economic group.

"Hundreds of women lined up around the block. They had advertised on posters in Yiddish, Italian, and English that they distributed throughout the neighborhood," Katz said. For weeks before the clinic opened, they'd canvassed the congested neighborhood of Brownsville, "seeking out mothers of large families and telling them where the clinic was to be found," and handing out hundreds of handbills, according to the local paper. (A contemporary news report noted, "It is significant that not one of the hundreds who knew of the place imported their information to the police.")

A October 22, 1916 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article describes the general scene:

The walk to Pitkin Avenue to Amboy Street reveals a violent contrast to Mrs. Sanders doctrine of limited families for the poor. There are baby carriages without number and each carriage contains at least one and in many instances two babies. There is no exaggeration in the statement that yesterday there were at least five baby carriages to every block of the walk and that estimate includes only one side of the street. ...

When a reporter went to the clinic yesterday there were three baby carriages standing outside the door. The carriages were not the right, well-appointed vehicles of the first-born either. Each one showed usage and very evidently had served as the carriage of state for at least two if not more babies. The mothers, who emerged in that moment, where the worn, dragged-out, weary-faced wives of men whose incomes are small and never assured-the type to whom a new baby is not a blessing but just another mouth to feed when there is scarcely enough to feed those existing already...

It was a convention of mothers yesterday afternoon - poor mothers, worn-out mothers. During a two hour watch not one was there who carried the fresh bloom of health on her cheeks. Not one had the joy of her life sparkling in her eyes. ....

The Eagle article also quoted a woman waiting to be seen in the Brownsville clinic:

"I am glad Mrs. Sanger has opened this place. I never saw her before my life. I never heard of her until today, but she will be mentioned... in my prayers. I have seven children and just now I am wondering how I am going to get shoes for them. They all need shoes and cold weather is coming on. My husband earns $15 a week when he works, and he is a good man to me. I do not know what we would do if another baby came. We could never care for it."

Sanger was convinced, said Katz, that "women couldn't enjoy equality unless they could escape fear of unwanted pregnancy, with that gone the playing field was more level in terms of work health political power -- everything they did could be undone by an unwanted pregnancy. In her view the only way to true feminism was if birth control could be legal, effective, and safe."

Women and men sitting with baby carriages in front of the Sanger Clinic. October 26, 1916. Courtesy of Social Press Association. Accessed through Library of Congress.

It wasn't just local women who came seeking knowledge about birth control. "People from many places out of the state visited the clinic today, one woman coming from Hartford Connecticut. A man from Port Jervis said he wanted information first hand to take back to a number of people there," reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Fighting For Women's Rights: Who's in Charge?

Sanger was a product of her era, and she said and wrote some reprehensible things; "an imperfect hero," one scholar called her.

But not to throw away the baby with the bathwater: she was right on the money when it came to women's basic need for birth control information, control over their own bodies, and having a full range of reproductive choices.

Some feminists see today's strident anti-abortion movement as a straw man, as a misogynistic foot in the door toward eliminating women's reproductive rights. On this, Sanger's insights are as fresh today as they were then: without reproductive rights, women have no shot at real freedom or gender equality in the workforce, politics, advancement or educational attainment.

On September 29, 2015 the president of Planned Parenthood was hauled in front of the US House of Representatives responding to a smear campaign of faked "videos" by anti-abortion activists, political rabble rousing, and a disinformation about the organization's expenditures. According to CNN, about 90 percent of Planned Parenthood's $450 million in annual federal funding, or nearly $400 million, is reimbursement by Medicaid. Yet radical right-wing politicians are threatening to shut down the federal government this week if a federal budget bill that includes Planned Parenthood funding remains in the legislation package.

I caught up with Professor Jean H. Baker, author of the recent biography Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion, to inquire about the connection between Sanger's 1916 Brooklyn clinic and the divisive public debate over Planned Parenthood today.

"It's like Alice in Wonderland," she said, noting that the very people who are seeking to defund Planned Parenthood are opposed to government in their lives, yet they're supporting government involvement in the most private of matters--women's sexuality.

"The connection is government intrusion. That's what the Comstock Act was. And that's what these folks in Congress are trying to do," she said. "It speaks compellingly to the problem women have today: to establish birth control and abortion and abortion as, simply, women's rights."

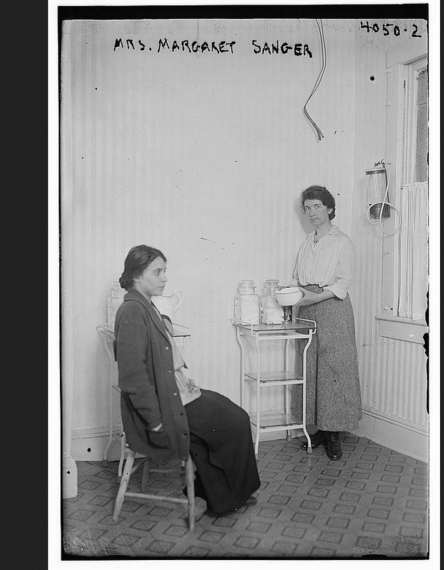

Birth control activist Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) with Fania Mindell inside the Brownsville clinic, probably taken Oct. 1916. Photo courtesy of the Margaret Sanger Papers project, NYU, 2014, Flickr Commons project, 2014 and Planned Parenthood/history website. Accessed through Library of Congress.

For more on Margaret Sanger in Brooklyn, see the article by Emma Jacobs on Place Matters.