It is never easy to change someone else's mind -- our child insists on playing video games during dinner, our parent refuses to let the doctor investigate the cause of recurring pain, and our spouse cannot be persuaded to spend the holidays with our side of the family. In politics, it is harder still -- our policy views contrast with theirs; our deep-seated beliefs run up against their impassioned pleas.

And yet influence is the bedrock of progress in politics. We cannot generally coerce others when we try to get out the vote, build coalitions, and pass legislation -- we must persuade. Our ability to do that is impacted greatly by two fundamentally different sets of assumptions we make about those who hold political views different from ours.

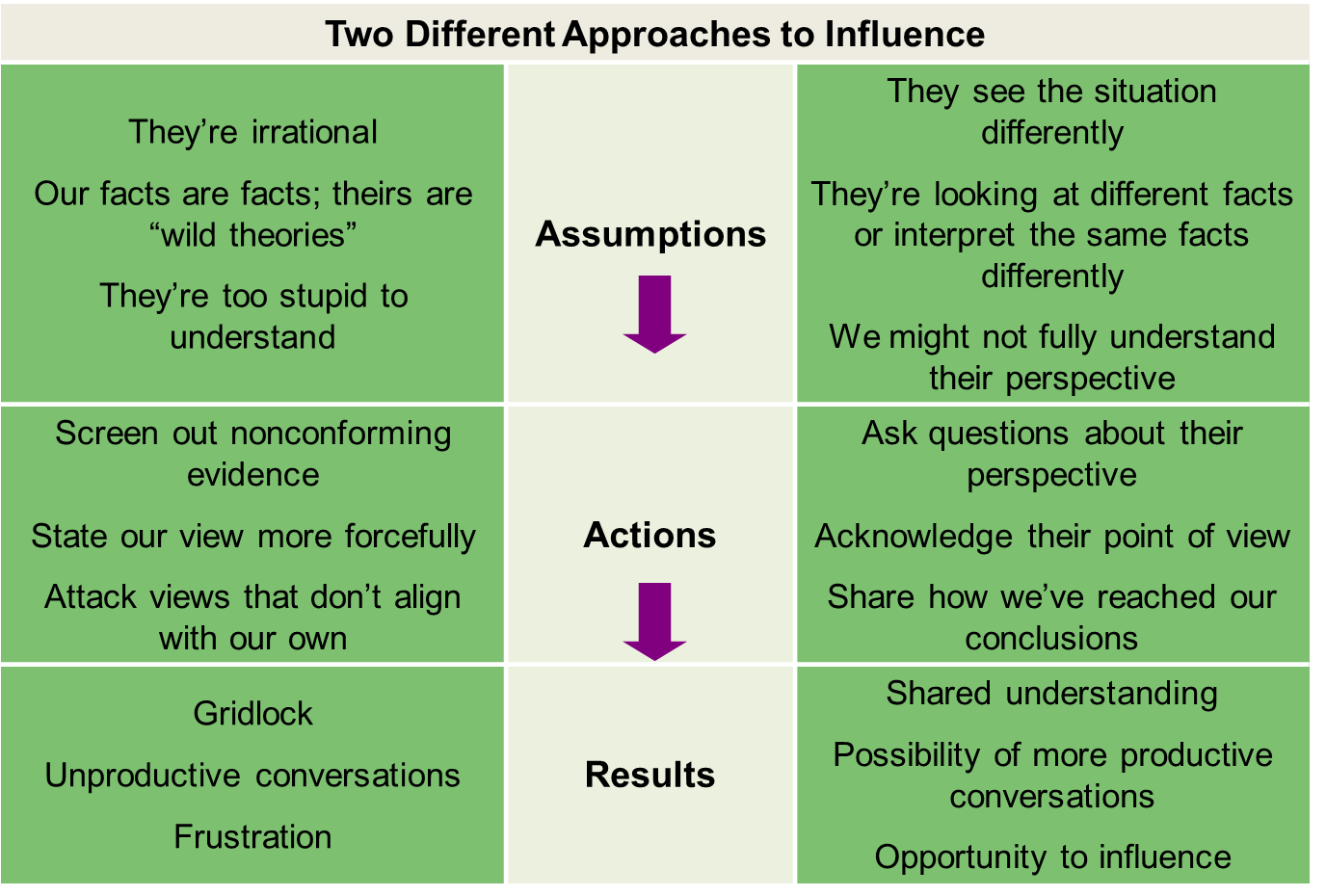

The first set of assumptions posits that our beliefs are truths and theirs are falsehoods; our views are right and theirs are wrong; we're reasonable and they're irrational; and we're enlightened and they're ignorant. Sadly, these assumptions are pervasive in the current political climate. A memo disseminated last week by James Carville and Stan Greenberg claims that Democrats' "facts are facts" while "the other side's 'facts' are wild theories that any reasonable person would find very, very weird." And that Republicans come from a "strange, strange planet" while Democrats, presumably, reside on Planet Earth.

Sure, these are marketing messages intended to appeal to the passionate partisans on one end of the political spectrum, but they are not without significant consequences. Such assumptions lead to an unsurprising set of actions: we attack perspectives that don't align with our own, we state our conclusions more forcefully, and we ignore any information that doesn't conform with our views. Know my political preferences? Then you know my favorite cable TV news channel. And so our conclusions turn into hardened, untested facts.

Of course, our political rivals respond in kind. The result is unproductive debate about different conclusions. We're likely to become frustrated when our effort to change their minds results in stalemate and gridlock. But we shouldn't be surprised. When was the last time we successfully reasoned with someone who was irrational? Or persuaded someone from another planet to adopt our point of view? Ultimately, nothing is as disempowering as assuming that the person we're trying to persuade cannot be persuaded.

A more empowering set of assumptions recognizes that political views are neither right nor wrong. They represent different perceptions. There are multiple facts and numerous truths. And the information we pay attention to (this campaign speech, that news article) is often different from what they focus on (this budget analysis, that endorsement). And even when we look at the same information, such as a debate, we interpret what we see and hear through the filters of our experience and beliefs and reach different conclusions about who won.

Recognizing that we see things in different ways empowers us to ask questions about their perspective, including the data they're looking at and how they reached their conclusion. It compels us to demonstrate an understanding of that perspective before sharing our own reasoning path. The likely result is a shared understanding of how we see things differently and the possibility of a more productive dialogue.

None of this is to suggest that every view we encounter makes a lot of sense or is grounded in compelling data. Carville reminds us that considerable evidence debunks claims that Planet Earth is 5,000 years old and that President Obama was born in Kenya. But approaching political discussions by laying claim to a monopoly on "the truth" and being completely closed to persuasion actually makes us less persuasive. And dismissing an alternative view on, say, the impact of tax cuts, as Carville does, as "not a view that makes any sense" makes it more difficult to influence that view -- and certainly more difficult to engage in civil discourse. There have been a lot of tax cuts throughout history and the result has not always been the same. This doesn't imply that everything evens out and it's all a wash. But it does suggest that a conversation about specific examples of the beneficial or detrimental impact of tax cuts is much more productive than a conversation that sounds like, "We need tax cuts," versus "No, we don't." Which of the two conversations we end up in depends on whether we assume there is even the slightest chance we might be missing something or whether we automatically assume the other side's view is nonsensical.

Mutual understanding doesn't translate into a vote or even guarantee a change in others' beliefs. But it certainly makes the opportunity for influence more likely. It also makes it possible to disagree without being disagreeable. Assuming Democrats are from Mars and Republicans are from Venus might make for a good sci-fi movie or a funny Halloween costume -- but it won't advance the political dialogue in this country.