Girls don't poop. Me, never have. Never will. It just doesn't happen. Or, that's what Joe thinks! We've been married for nine years, and he has never once seen or smelled my business. How have I pulled this off? I don't do it when he's around or awake. In an emergency, I have my ways of pooping so he won't hear, smell, or see. It's a challenge.

That's Melissa Gorga, one of the "Real Housewives of New Jersey," sharing one of her secrets of a very strange marriage.

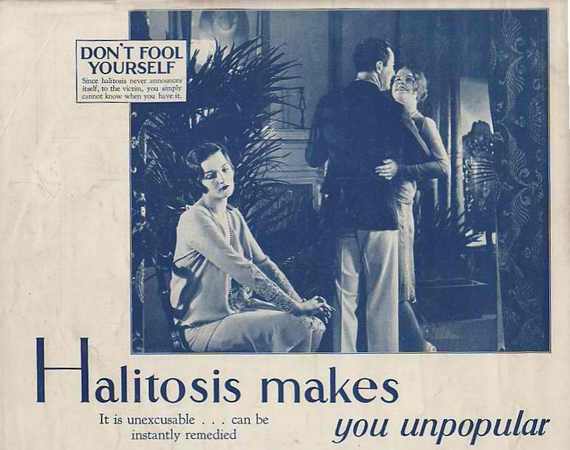

She takes it to an extreme, but shame about bodily functions and their evidence has long been an advertising staple, from halitosis to "ring around the collar" to that "not so fresh" feeling to to, yes, "girls don't poop." (The last one tries to lampoon the poo-phobia even while reinforcing it.)

Photo courtesy of Johnson & Johnson.

This deep shame around a simple biological reality is one of Toilet Hackers' biggest challenges. People can have such an aversion to thinking about number two that they just shut down completely when I bring up something like open defecation, or OD. OD is exactly what it sounds like -- crapping out in the open, in the bushes, alongside train tracks, on riverbanks, in any available spot. Over a billion people practice OD, which poses the most intense problems with contamination and environmental damage.

Until fairly recently, global sanitation improvement focused on getting specific hardware systems in place -- offering subsidies to build pit latrines, for instance. But too many shiny new facilities turned into hen houses or storage sheds, so the focus has wisely shifted to changing behavior. Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) has become the most widespread and, in some ways, the most controversial behavioral-change model. A trained facilitator visits a village or neighborhood where OD is common and tries to elicit a sense of awareness and shame among the residents, thus motivating them to make and sustain behavioral changes. As Kamal Kar originally conceived of it, CLTS involves no financial subsidies but does provide ongoing support and monitoring.

CLTS techniques are both confrontational and communal. The "walk of shame" involves strolling through the area to point out all the turds. The facilitator might ask participants to draw a map of the community, including exactly where everyone does their business. Or the group might calculate just how much ordure the community produces. (Roughly a pound per person, per day.) Or the facilitator might take a blade of grass, run it across a stick they'd just poked into a fresh pile of human crap, then dip the grass into a pitcher of cool, clean water. Does anyone want to drink the water? Of course not. That leads to a discussion of how human dung, and all the diseases and parasites it contains, is spread throughout the community.

The idea is that once everyone openly acknowledges -- perhaps for the first time -- that they're literally eating and drinking each other's shit, then they're motivated to come up with solutions: constructing improved toilets from available materials, declaring that the community is now open-defecation free, and enforcing that new norm.

I've always been a little ambivalent about CLTS. It's proved very successful in many areas, especially sub-Saharan Africa, and I'm a fan of its most basic principles: putting the power in the hands of the community itself and encouraging immediate action instead of waiting for a perfect answer. But the emphasis on shaming makes me uncomfortable. It's a crude instrument, with the potential to crush as well as inspire, so I'm happy to see a shift in emphasis from shame to dignity and inclusiveness. And CLTS practitioners themselves acknowledge that triggering shame is just the first step on a journey to the same goal: empowerment, pride, and dignity.

CLTS has been in practice since 1999, long enough to produce both offshoots and detractors. At the recent Water and Health Conference, sponsored by UNC's Water Institute, several researchers presented studies of behavioral programs in the field. (Links to all the presentation materials are here.) Jay Graham at George Washington University evaluated ten anti-OD behavioral change programs and found that even though facilitators ranked follow-up and monitoring as the most important activity, the large majority of each program's resources went to triggering activities, with relatively little ongoing support. "I think there's a little bit of a silver-bullet mentality," said Graham. "That we can just do this three-hour emotional-triggering event and move on and they'll solve the rest on their own." Graham also pointed out that there's wide variation in how behavioral programs, CLTS and otherwise, are implemented: exercises used, length of interaction, facilitator training, community resources. Until we know what's being done, it's hard to evaluate what really works.

That focused research must include sanitation marketing, according to Jan Willem Rosenboom of the Gates Foundation. He pointed out that one geographic area contains many markets. People who say, "I don't need a toilet, I like open defecation and shit doesn't spread disease" won't respond to the same message that resonates with people who want an improved toilet but can't afford one. More broadly, Rosenboom calls for sanitation marketing to apply social and commercial marketing approaches to scale up the supply as well as the demand for improved sanitation facilities. Those facilities must include not just latrines and toilets themselves but extend through proper processing of the waste itself, ending what he calls "institutional open defecation" -- systems that just gather up and dump unprocessed fecal sludge.

So as it turns out, the same powerful messaging systems that make us all wonder if our teeth are white enough and our hair is shiny enough might be part of the solution to a far more serious problem. The question is, which side of the coin will be emphasized: dignity, or shame?