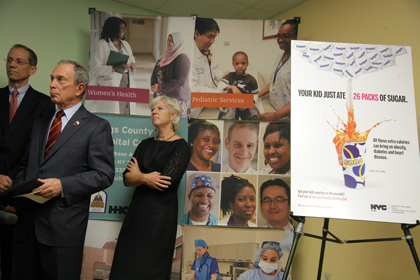

Lately there has been a lot of hoopla in the Big Apple about the federal food stamp program, now officially known by the snappy acronym SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.) Over 41 million Americans (and 1.7 million New York City residents) receive food stamps. In September, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg asked the USDA to allow a pilot program to prohibit food stamp recipients from buying non-diet soda (and other sugar-sweetened beverages) in New York City. The Mayor cited an estimate that in 2009, food stamps bought $75-$135 million worth of soda and other sweetened beverages in New York City. He noted the costly negative health impacts (such as obesity, diabetes, and malnutrition) associated with such products.

The American Beverage Association, whose members are producers, marketers and distributors of non- alcoholic beverages, immediately decried the proposal as "just another attempt by government to tell New Yorkers what they should eat and drink, and will only have an unfair impact on those who can least afford it." The non-profit New York City Coalition Against Hunger echoed the ABA, telling the USDA that accepting the proposal would "punish low-income people" and that "there are much more effective ways to address obesity." Andy Fisher of the Community Food Security Coalition acknowledged that banning soda for food stamp purchases raises tough questions, and recommended that the USDA grant the waiver only if they also required the City to invest in programs that would redirect the amount no longer spent on sugary beverages to more healthful purchases. Everybody, it seems, has an opinion. What to think?

The history of the Food Stamp Program is instructive. What were the food stamp program's original goals and guidelines, and when and why were food stamp recipients authorized to use food stamps to buy sugar-sweetened beverages (a/k/a soft drinks, pop, and soda)?

A March 14, 1939 article in the Washington Post described the food stamp program as a farm recovery program -- the unemployed would eat the Nation's surplus food. Under the sub-headline "$1.50 in Food for Dollar," the Post explained:

The plan provides the grant by the Government of $1.50 in food orders to the beneficiaries for each dollar of the WPA wages or dole money they expend. For each cash dollar, an unemployed person would get $1 in orange stamps and 50 cents in blue stamps.

Orange stamps are good for any grocery item the purchaser elects, except drugs, liquor, and items consumed on the premises. Blue stamps, however, will buy only surplus foods -- dairy products, eggs, citrus fruits, prunes, fresh vegetables, and the like.

In other words, the government was willing to subsidize food purchases by those in need, so long as those purchases made a dent in the agricultural surplus of the nation. From the inception, the government had a say in what could be purchased with food stamps. And, because surpluses change with the natural cycle of the seasons, the list was updated monthly. On September 26, 1939, the New York Times published the October surplus list:

The list, effective Oct. 1, includes butter, eggs, raisins, apples, pork lard, dried prunes, onions, except green onions; dry beans, fresh pears, wheat flour and whole wheat flour, and corn meal. Fresh snap beans were designated as surplus for Oct. 1 through Oct. 31.

Raisins, apples, pork lard and snap beans appeared on the list for the first time. Foods which will be removed from the list on Oct 1. include cabbages, fresh peaches, fresh tomatoes, rice, and fresh green peas.

Throughout the program, truly fresh produce was the name of the game. In July 1941, at the height of the growing season, all fresh vegetables were placed on the surplus list. At the same time, "soft drinks, such as ginger ale, root beer, sarsaparilla, pop, and all artificial mineral water, whether carbonated or not," were removed from the food stamp list, and retail food merchants were warned not to sell those items for orange stamps or blue stamps. However, natural fruit juices, "such as grapefruit, orange, grape or prune" were not considered "soft drinks" and could still be sold for orange stamps. The press did not report any kerfuffle over the removal of soft drinks from the list of items that food stamps could buy.

A 1943 New York Times blurb regarding the upcoming end of the surplus program reported that

The following foods may be obtained during the final period with blue food stamps in any eligible retail food store: corn meal, hominy grits, fresh apples, fresh grapefruit, fresh pears, wheat flour, enriched wheat flower, self-rising flour, enriched self-rising flour, whole wheat (graham) flour, dry edible beans, Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes and fresh vegetables.

The announcement says that vegetables obtainable for blue stamps shall not include melons, avocados or rhubarb, or processed vegetables -- frozen, canned, dried or pickled.

As World War II shifted in to high gear, crop surpluses became crop scarcities, unemployment dwindled, and the food stamp program came to a an abrupt close. (However, as Jan Poppendieck pointed out in her book Breadlines Knee-Deep in Wheat, "the truly unemployable needed food assistance more than ever as food prices rose sharply under the pressure of wartime scarcities.")

Immediately after the program ended, elected officials attempted to introduce legislation for a new Food Stamp program, a futile exercise that repeated many times over the next two decades. But, by 1964, the coupling of hunger and agricultural surplus was again politically viable. Congress enacted the Food Stamp Act of 1964 "to permit those households in economic need to receive a greater share of the Nation's food abundance."

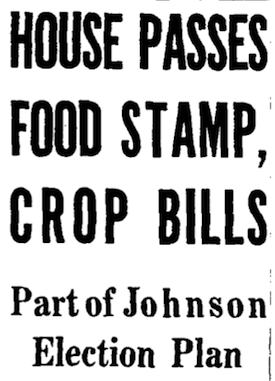

The House version of the bill initially defined "eligible foods" as "any food products for human consumption except alcoholic beverages, tobacco, and foods identified as being imported from foreign sources." The bill was amended to also exclude from purchase "soft drinks, luxury foods, and luxury frozen foods as defined by the Secretary." The House passed their version of the bill on April 8, 1964.

![]()

But when the conference bill went back to the Senate, the Senate removed the exclusion of soft drinks (as well as luxury foods) because they presented an "insurmountable administrative problem." (While the insurmountable administrative problem was not defined, nor discussed in the Senate hearing, it is worth noting that the first item to bear a Universal Product Code, Juicy Fruit gum, was not scanned until ten years later, at a supermarket in Troy, Ohio on June 26, 1974.) The Senate also protested that the dictionary defined "soft drinks" as "those not containing spirituous liquor, so that milk, orange juice, coffee, and other beverages would technically be excluded." Finally, the Senate cited studies showing that:

Food stamp households concentrated their purchases on good basic foods. For example, fruit and vegetable consumption was largely accounted for by seasonally abundant fresh items; potatoes, greens, tomatoes, cabbage, apples, and assorted citrus fruits.

Still, Senator Paul H. Douglas of Illinois expressed concern that the benefit would be used for items other than "good basic foods," and he proposed an amendment to prohibit the use of stamps to purchase "carbonated soft drinks." That amendment was not included in the bill that the Senate passed unanimously on August 11, 1964.

So there you have it. President Johnson signed the bill into Law on August 31, 1964. At the ceremony he said "I believe the Food Stamp Act weds the best of the humanitarian instincts of the American people with the best of the free enterprise system." With his signature, the ability to purchase soft drinks with taxpayer-funded food stamps became a reality and, forty-six years on, that reality remains the same today.