I explained in a recent companion post why the distribution of airline reservations was supposed to be so free, open, and transparent that it would not need continuing regulation, which is why the industry was deregulated in 2004. And yet American Airlines and US Airways have filed suit, claiming precisely the sort of abuses that were supposed to be impossible in an Internet age. The details of the history can be found in the companion piece. Here I describe the nature of the litigation, the implications for a wider range of Internet businesses, and possible remedies.

The Nature of the Current Litigation: The Case of US Airways V. Sabre

US Airways sought to provide a range of pricing options through travel agencies, as it already does on its own websites. These options would allow consumers to choose to pay for checked bags, or not to do so, to choose to pay for meals, or not to do so, to choose to pay for greater legroom or priority seating, or to forego advance seat selection entirely. This is a shift to a model where consumers only pay for the products and services they use. US Airways has been blocked from offering these complex pricing strategies through traditional or online agencies, since US Airways' agreement with Sabre prohibits US Airways from using alternate mechanisms for offering any services to agencies that are not available through Sabre. This limits the products and services available to the approximately 50% of US Airways' customers who book through agencies.

The essence of the US Airways complaint is:

- Sabre has limited their ability to compete by limiting the range of services that they can offer agencies

- Sabre has limited their ability to compete by limiting the descriptions of services that they can offer through agencies;

- Sabre has eliminated their distribution options and locked them into a channel that is both very expensive and of limited capability

On its surface, the complaint would appear absurd. If agencies are not getting the full range of options, why would they remain with the GDSs? At a minimum, wouldn't they welcome the direct connection alternatives that airlines have developed, and use them at least occasionally to book service options that were not available through the GDSs?

This is where the power of the third party distribution model comes into play. While the airlines pay the GDS fees, the agencies actually are paid for their GDS use. Any use of an alternative, parallel, direct connection option reduces their GDS volume and reduces their payments. Worse yet, for the agencies, significant use of alternative direct connection services could drop the agency below usage thresholds and cause them to lose all of their GDS payments. Leaving the GDS system is simply not an option, since there are massive termination penalties. It would be hard to get travel agencies to move to an alternative form of distribution in which they gave up the subsidies they receive from airlines, and instead are hit with penalties for contract termination. The GDSs remain significant, and the two largest (Travelport and Sabre) still account for 90% of agency bookings in North America. Interestingly, these are all abuses that were blocked by the CRS regulations of 1984; they have reemerged largely because the deregulation of 2004 assumed that this form of abuse could never occur in an open Internet world.

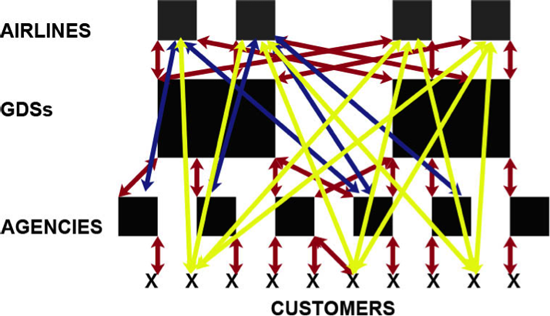

Many of the interactions between consumers and airlines that were predicted in Figure 2 simply have not occurred. Many of the red lines remain, and fewer of the blue lines were introduced than expected. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.--The structure of travel distribution; with third party payer mechanisms in place there is far less use of direct connection by agencies than expected and far more use of GDSs. Since there is less booking through direct connection than expected, there are far fewer blue lines than expected.

A significant fraction of corporate travel is still is booked through agencies. Corporations often receive significant benefits for using agencies. There are numerous reporting, assistance, and travel expense management functions that require integrating data from numerous travel providers, and for which corporations prefer the neutral services of an independent agency. If corporations require their employees to use agencies to book corporate travel most employees will comply.

It is initially surprising how much individual passenger traffic is also booked through agencies, rather than through airlines own websites; this is even more surprising when considering the greater range of options available from the airlines themselves. This can be explained through a variety of causes:

- Airlines have not done much to earn the trust of passengers, and many believe that lower fares are available through online agencies like Orbitz and Travelocity than through the airlines themselves.

- Customers appreciate the convenience of getting their pricing information from a single site like Orbitz or Travelocity, and no airline is presently providing equivalent comparison-shopping tools for flights.

- The volume of advertising that promotes online agencies and their prices and price protection programs greatly exceed the volume of any individual airline; additionally, airlines' advertising focuses on service, not on the advantages of discount online pricing.

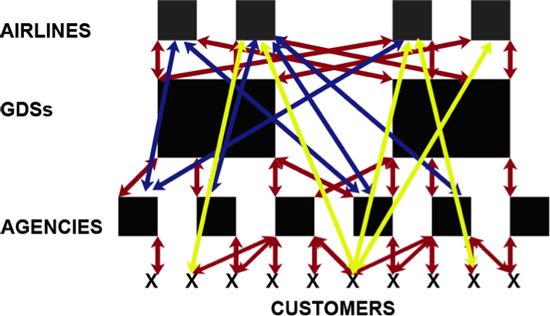

Figure 4.--The structure of travel distribution; without customers corporate customers remaining with agencies and leisure customers remaining with online agencies, there is less use of direct booking and fewer yellow lines. With increased use of online agencies like Orbitz and Travelocity, there are actually more red lines. The diagram does not look much like the expected shape of the industry, as shown in Figure 2.

Why Should Consumers Care?

If our analysis is correct, the continuing power of the major GDSs (Travelport and Sabre) significantly reduces consumers' choices of travel options and service alternatives when booking travel, thereby increasing travel costs. American travelers do not have the range of discount travel products available to them when they book through traditional agencies or online agencies. Additionally, the GDS fees are among largest single avoidable expenses incurred by airlines, representing approximately 2.5% of each ticket on average, likewise increasing consumer costs.

- The first point is based on the observation that while consumers have flocked to the lower-price options made available through Air Canada's website, the GDSs are not permitting US carriers to offer the same product choice to US consumers. The GDSs require that US carriers offer agencies only fares and only products that are available through the GDSs; since the GDSs are not technologically advanced enough to handle the full breadth of offerings that US Airways and other US carriers desire, the GDSs are limiting their availability.

- The second point is based on the observation that any increase in airline costs, such as increased fuel costs, inevitably results in higher consumer prices.

Why Should Regulators Care?

Most academics expected that the web would automatically enable transparency and competition. In particular, it was believed that the web would automatically create numerous vendors competing with the widest array of goods and services at the lowest possible price, and it would automatically result in the widest range of competing channel and distribution alternatives. In the resulting global parimutuel mall, antitrust concerns would be obsolete. With perfectly informed consumers choosing from perfectly competitive alternatives, consumers would make wise choices, based on their valuations for price, convenience, and features. They would enjoy wider selections than a mall and better prices than Wal-Mart; they would know what they want, know what the alternatives were, and know how to choose. In this perfect free market world no paternalistic regulator could ever hope to second-guess the wishes of the marketplace.

Regrettably, it has not worked out as expected.

Third party payer mechanisms retain enormous power, continue to reduce consumer choice, and continue to add significantly to consumer expenses. The remaining need for Internet regulation may not resemble traditional antitrust concerns, but that does not mean that there are no remaining regulatory issues. As I have argued previously, the power of third party payer business models requires rethinking the regulation of Internet businesses. The growing power of businesses based on these models, including Groupon, Google, and the GDSs, demonstrates that the need for Internet regulation remains very real.

Perhaps the most dangerous abuses of Internet business models result in real but invisible consumer harm. Internet intermediaries harm primary service providers, who inevitably pass the harm through to consumers as higher prices, reduced choice, or both. Consumers do get the convenience of shopping for flights at traditional agencies and OTAs, and consumers obviously do value convenience. Consumers pay higher prices for travel because of the airlines' higher distribution expenses, just as they would pay higher prices if fuel costs or airport landing fees increased, but they do not complain because they are not aware that they are paying higher prices. Many travelers have reduced selection, including reduced access to lower cost flight alternatives, because airlines cannot offer these products through agencies and OTAs, but again consumers do not complain because they are not aware of the reduced choices.

The debate over the remaining need for Internet regulation is complex, and there are many affected parties, some of which are lobbying quite hard to protect the status quo. It is, of course, only right that the GDSs should seek to preserve their currently successful business model. It is only natural that agencies should seek to preserve a business model in which they are the recipients of payment for directing business to the GDSs. Regulators may not see antitrust abuses online because it is apparently so easy to enter; this ignores the fact that with third party payer mechanisms, a new entrant's offering a new alternative may not shift share if customers receive subsidies to remain with their original server. Regulators may not see essential facilities violations when it is again apparently easy to offer a new alternative; this again ignores the fact that with third party payer mechanisms a new entrant's offering an alternative may not capture share if customers receive subsidies to remain with their original server. It is unfortunate that consumer protection agencies see the new and more complex product mix in air travel as harmful to consumers; recent analysis of industry data indicates that where greater choice in air travel options exists most consumers have used this choice to achieve lower fares.

The harm of third party payer businesses is real and may be among the most significant emerging regulatory problems of the online world. The actions I would recommend regulators consider, in the case of GDSs as well in others, include:

- Limiting the fees that can be charged for participation, whether GDS fees to airlines, Google charges for keywords, or other fees in other settings.

- Ensuring freedom of choice; as Google says, its users are only a click away from another search engine, and airlines are hoping to achieve the same freedom of choice for travel agencies.

- Limiting vertical integration because of the real and inevitable harm from preferential treatment for the offerings of the system provider, whether this involves preferential treatment of flights operated by the airline that owned the specific CRS (as was true before 1984) or preferential ranking of services operated by a search engine's owner (as is currently alleged).

1 - Among the highest unavoidable costs incurred by U.S. airlines are fuel (25.4%), labor (24.7%), professional services (8.3%), aircraft rents and ownerships (6.7%) and non-aircraft rents and ownerships (4.4%).