Many western economic pundits continue to believe that China will experience a hard landing in the near term, even though its economic history over the past 20 years has demonstrated that in spite of global and national economic turmoil, China has always landed on its feet. Although the future direction of Chinese economy is unclear, we do not think China is heading for a hard landing in the near term, but it must adapt to new realities and become more agile than it has been in the past in order to avoid a hard landing in the longer-term.

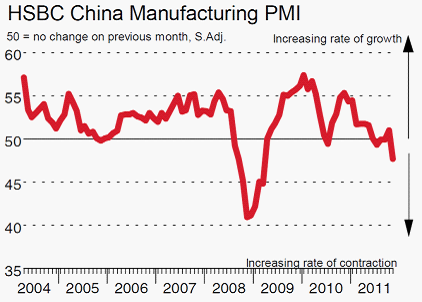

The ongoing erosion of China's largest export markets -- in Europe and the U.S. -- combined with cost push and wage inflation, are eroding the comparative advantage of China's manufacturing industry. As noted in Graph 1, the manufacturing sector is bleeding. The Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) has dropped to 49, approaching the lows seen in 2008, and the first time since February 2009 the PMI has contracted. Orders are declining and stocks are piling up. But this has nothing to do with the government's adoption of the tight monetary policy -- rather, structural changes in China's economy.

Graph 1

It has become difficult for small and medium-sized private businesses (SMBs) -- the driving force behind China's manufacturing industry -- to access credit. More than 70 percent of China's banking market is controlled by the "big four" -- Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China. These state-owned commercial banks skew monetary resources towards state-owned enterprises or other privileged national corporations. This allocation deficiency in China's banking system has created a breeding ground for China's large and complicated shadow banking network, where most credit-starved private SMBs seek costly funding. The shadow banking system is little regulated or monitored, and is awash with cash that earns negative real interest rates in commercial banks. In one month last year, 467.8 billion yuan (approximately USD 74 billion) of individual deposits were withdrawn from commercial banks, some of it chasing positive yields in the shadow banks.

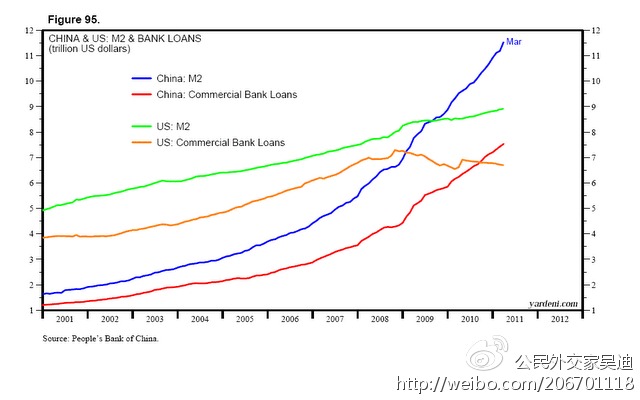

In spite of this, and contrary to what many might like to assume, China now is not even close to suffering a liquidity crisis. There is more than enough liquidity to go around. As noted in Graph 2, China's M2 stands at approximately USD 11.6 trillion, exceeding the U.S. (at USD 8.98 trillion) and Japan (at USD 9.63 trillion). Regardless of all the hype about tight monetary policy, in 2010 Chinese banks issued 7.95 trillion yuan (USD 1.26 trillion) of loans, breaching the government's target ceiling of 7.5 trillion yuan. In 2011, total new loans were close to 7.5 trillion. As of October 2011, the outstanding balance of RMB deposits totaled 79.2 trillion yuan, representing year-on-year growth of 13.6 percent.

The People's Bank of China's (PBOC's) rate hike removed only 4.75 trillion yuan from circulation. According to Fitch, China's total social financing in 2011 might top 18 trillion yuan (USD 2.8 trillion), a rise of 3.5 trillion yuan from the official target, due to inflows of non-banking liquidity. The PBOC claimed total social financing for the first three quarters of 2011 of 9.8 trillion yuan, 1.26 trillion yuan less than 2010. The PBOC's data suggests an effective tightening monetary policy while the Fitch report implies the opposite, raising question about the efficacy of PBOC policy. Yet, in spite of all the doom and gloom that underlay China's recent economic performance, China's credit expansion -- against all odds -- remains breathtaking.

Graph 2

Monetary policy alone cannot fix the structural deficiencies of China's economy, whose well-being is highly leveraged on the consumption of European and U.S. consumers. The increasing substantial wealth gap in China has shackled domestic demand to such an extent that it fails to make up the difference left by the European and U.S. markets. China is now saddled with a serious excess capacity problem, which forces down marginal returns on investment, making it more effective in causing inflationary pressures than propelling GDP and employment forward. This is a sign of serious over-investing and overheating.

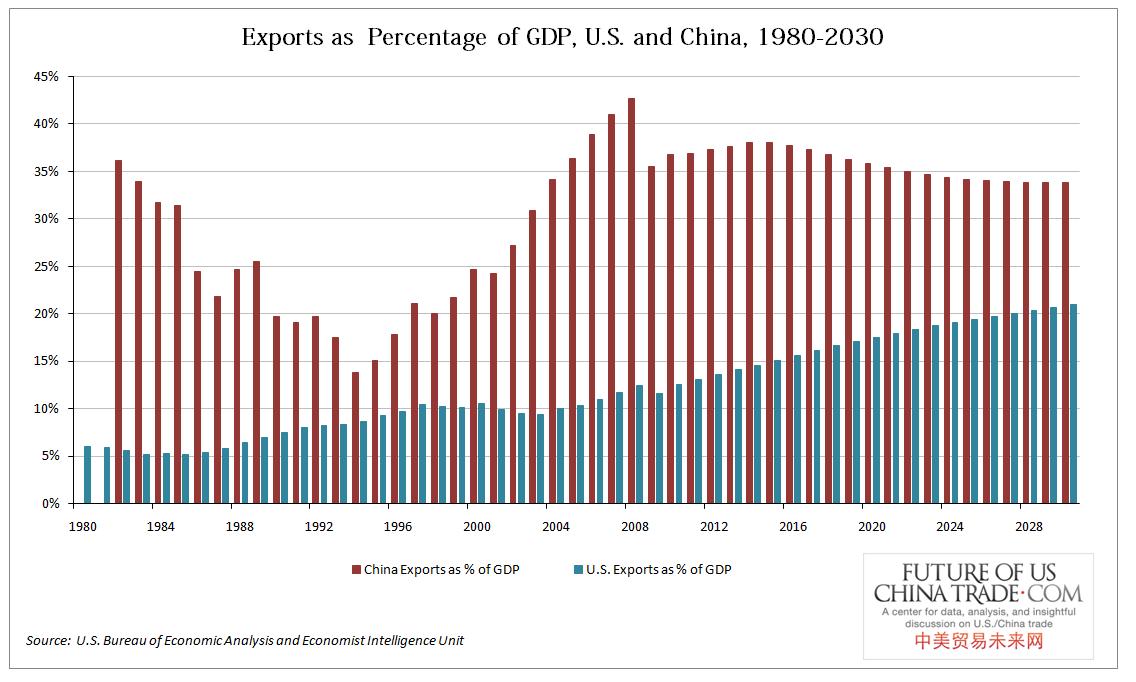

In 2010, China's export/GDP ratio was about 37 percent, while its investment/GDP ratio was 45.8 percent. According to research by David Kotz and Andong Zhu, China's exports and fixed investment have contributed almost 70 percent of GDP growth since 1999, while domestic consumption contributes roughly 30 percent. Using export and investment to push the economy forward is what has becomes known as the Beijing consensus, which works beautifully when the world is prospering, but works poorly when the tables turn. Given that Europe and the U.S. must check their deficit-fueled consumption economies into long-term rehabilitation, they must increase their chronically low savings rate, produce more and import less. This is likely to mean that the export-led growth engine China has known for the past 20 years will be gradually slowing down. According to Economist Intelligence Unit and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (see Graph 3), China will be depending on an export-led economy for at least another 20 years. Something must change in the interim. A consumption-led economy is the only way out, unless China decides it wishes to fight for a greater share of overseas markets and is prepared for the possibility of trade wars with its largest competitors.

Graph 3

Although China's Consumer Price Index recently tumbled to 4.2 percent -- the lowest level since September 2010 -- the country remains inflation-prone. China is the world's biggest importer of food and commodities, but cost-push inflation for these items remains ever present. When combined with negative real interest rates and diminishing marginal returns in industry pushing more and more money into asset investment and speculation, inflation will remain a persistent threat.

The Chinese government would be wise to unleash the "big four" banks and allow them to operate on a truly 'commercial' basis, to allow for more efficient monetary allocation. China should transform its labor intensive, low value-added economy to a more high value-added knowledge economy. And it should reform the wealth redistribution system to empower its broad consumer base and encourage a consumption-led economy.

While the U.S. enjoys the luxury afforded it by continuing to have the dollar as the world's de facto currency, and can link hands with its major trading partners to effectively export its liquidity issues and inflation, China enjoys none of that. In this regard, the Beijing consensus makes little sense. Pegging a country's growth to a certain set of policy tools or a certain reserve currency (the U.S. dollar in this case) is equally dangerous. The world is changing fast. The battle between Keynes and Friedman has long proven that the only consensus that really makes sense in the long haul is to adapt and change. This is the consensus China should be embracing, or it may yet face what has been until now been only a mythical hard landing.

This post was written by Daniel Wagner and Dee Woo.

Daniel Wagner is CEO of Country Risk Solutions, a cross-border risk consulting firm based in Connecticut (USA), Director of Global Strategy with the PRS Group, and author of the forthcoming book, Managing Country Risk (March 2012). Dee Woo is a lecturer in economics at the Beijing Royal School.