Editor's Note: This post is part of a series produced by HuffPost's Girls In STEM Mentorship Program. Join the community as we discuss issues affecting women in science, technology, engineering and math.

In Academia, it's all about the money. Even when you're not paying for classes as a graduate student or a professor, you still need to find funding for your research. As a Ph.D. student in Paleontology at the University of Oregon, I am fortunate enough to be on a teaching fellowship, but I still have to find external funding for trips to museums to photograph all the awesome fossils I examine. Where do I get that funding? From those mythical, magical and incredibly elusive beasts known as Grants, Awards, Fellowships and Crowdfunding, the last of which is a new and fancy addition to the triumvirate of other people's money scientists spend so much time begging for. In honor of International Day of the Girl Child, I wanted to highlight the financial barriers women in STEM face in the area of funding.

This year's funding application season is almost upon us, which means that my fellow students and I are getting ready for another round of talking ourselves up and finding ways to make our research sound important to people who don't know anything about it. And in a surprising* twist of fate, all my female colleagues and I have to work harder to get these than our penis-possessing** counterparts. Gender bias is an unfortunate part of pretty much every part of working in STEM fields. It makes it harder to get into (and out of!) school, it affects whether or not you get hired for jobs, and it affects whether or not people think your research is worthwhile enough to fund. Garlic is the magic spice that makes everything taste better in cooking; penises seem to be a similar ingredient in STEM.

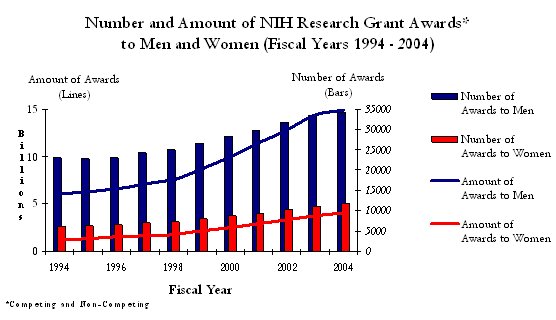

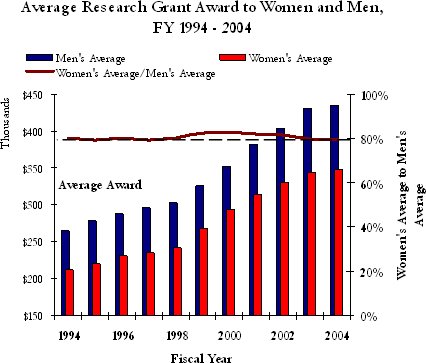

For a visual representation of this problem, here are some graphs from the National Institute of Health (NIH).

Not only does the number of grants awarded to women differ from that of men, the amount of money in that award also is different.

Not only does the number of grants awarded to women differ from that of men, the amount of money in that award also is different.

No wonder we all have penis envy.

These graphs are about 10 years old at this point, but the problem persists. Male applicants continue to receive a higher percentage of awards than expected when considering their percentage of the applicant pool. In fact, between 2000 and 2010, men were 8 times as likely to win a scholarly award than women (Lincoln et al., 2012). They were consistently more likely to win, regardless of their representation in the applicant pool.

One of the potential reasons behind this gap is the overwhelming presence of men on committee boards, especially as chairs. Lincoln et al (2012) found that committees chaired by men awarded 95 percent of their awards to men, though only 79 percent of the applicant pool was male. When the committee was chaired by a woman, a mere* 77 percent of the awards went to men (when the applicant pool was 66 percent men).

But one place where women do better is in teaching and service awards. Now, lets not get too crazy here - they don't actually do better than men (HAH FUNNY JOKE), but up to about 40 percent of awards for teaching or service go to women, as compared to the ~5-25 percent that go to women in some STEM fields. Woo-hoo! Of course, early education teaching has been a field traditionally dominated by females anyhow... perhaps that's finally where the "Old Girl's Club" is that I have been desperately seeking.

You can't join the OGC if you don't know how to party (on Estradiol)

So WTF, world, why aren't ladies getting their dues? Lincoln et al. (2012) think the Matilda Effect is to blame. The Matilda Effect is a sociological term describing the phenomenon where achievements of women are either overlooked entirely or ascribed to men. This bias plays a role in the life of every female academic: it makes it harder for them to get high-level jobs, harder to stay in academic careers, and harder to get the grants and awards that boost their chances at the first two parts of this sentence.

So what happens when you look at women-only awards? Well, that helps increase the numbers of women who are funded, that is certainly true... but thanks to the Matilda Effect, it may actually decrease the perceived significance of women's work. Awards that are granted only to women reinforce the idea that women's work is somehow inferior and "needs a boost" in order to achieve equal success. This is very similar to some of the criticism of scholarships aimed at increasing diversity - though they increase diversity, they can also cause systematic undervaluing of minority contributions.

I want to make it clear that this bias is not necessarily overt. While conscious sexism is still a problem, it is less politically correct these days than it used to be and therefore a lot less prevalent. The root of this and other sex-based discrimination is not (always) the obvious, in-your-face jackassery that our predecessors faced, but instead the unknowing bias that has been implanted in everyone by the culture that we live in. Hell, even women pick men over women for jobs! Female participation in academia has often been referred to as a "leaky pipe:" though these days there are more and more ladies entering that pipe, somehow very few of us manage to get to the end of it.

So ladies, it's GAF(C??) season. Time to strap-on (heh) our boy!brains and make ourselves out to be about 60-95% more important than we actually are because we're going to need that edge. In the words of Britney Spears, we, more than all the testosterone-laden nerd-dudes around, had better work bitch.

But standing in the way of this is how we are socialized: women are taught repeated, often subconsciously hammered-home lessons on being submissive, on sharing the credit, and on not lauding our many and varied talents. We can't let ourselves get swept under the rug because we've been train that boasting is bad and false humility is good. Funding is nothing but a biggest dick competition, and since we don't have dicks what we need to be doing is overcompensating!

No, not with one of these.

Amy Atwater (a fellow guest-writer on the Huffington Post with whom I co-write a blog making very extravagant penis jokes) once gave me an incredible piece of "fund thyself" advice: to create a list of all the fantastic things I've ever done. The things you put on this list should be concrete and measurable, and the more they seem like bragging, the better (Pro tip: the more you can divide things up, the longer your list looks and the more awesome you feel). Don't know what to put on that list? Ask a friend - ladies in particular are pretty good at noticing the wonderful things our colleagues do despite how bad we are at admitting those things to ourselves.

Label this list "Why I am Awesome," and keep it open on your desktop. Turn on Leechblock so you don't click onto facebook every five seconds when you remember how much you hate grant-writing, then pump the tunes, and oversell yourself until your pants have lit on fire. Finally, always remember the words of Yolandi Vi$$er:

She's got dollar signs in her name. I'm pretty positive she's on to something.

*sarcasm.

**speaking only of those possessing them naturally, rather than those who possess them in jars.

For more on funding for women in science, here is a list of recommended reading:

Lincoln, Anne E., Stephanie Pincus, Janet Bandows Koster, and Phoebe S. Leboy. "The Matilda Effect in science: Awards and prizes in the US, 1990s and 2000s." Social studies of science 42, no. 2 (2012): 307-320.

Scholars' awards go mainly to men. Anne E. Lincoln, Stephanie H. Pincus & Phoebe S. Leboy. Nature pp 469.

Popejoy et al. Is STEM still just a man's world? Awards and prizes for research achievements in disciplinary societies go mainly to men despite growth in women's participation. Association for Women in Science.

Sex/Gender in the Biomedical Science Workforce. OER Public Websites Archive. Department of Health and Human Services.

Gillinder Bedi, Nicholas T Van Dam, Marcus Munafo. 2012. Gender inequality in awarded research grants. The Lancet, Volume 380, Issue 9840, Page 474

Long, J. Scott, and Mary Frank Fox. "Scientific careers: Universalism and particularism." Annual Review of Sociology (1995): 45-71.