"We all live in a prison. Most of us don't know we live in a prison." Janey, from Blood and Guts in High School by Kathy Acker, 1978

Twenty years ago when Marcia Tucker, founder and (then) director or The New Museum, organized Bad Girls (Part 1), she wrote of artists "using a delicious and outrageous sense of humor to make sure not only that everyone gets it, but to really give it to them as well. That's what we mean by 'bad girls.'" Of all the artists I know working today from such a critical position, few have as effectively underscored the transgressive nature of humor in their work as Laura Parnes has. It helps, of course, that's she's a wickedly funny person with a pitch-perfect sense of comedic timing, gleefully willing to subvert the sanctity of art as well as the institutions that circumscribe its production.

Conjuring Julia Kristeva's notion of the abject, "what disturbs identity, system, order....What does not respect borders, positions, rules", Parnes creates a willful ambivalence in her work through terse, non-linear narratives that blur the line between film and video art. Sometimes she puts the viewer in her sights right alongside the more obvious targets - pop culture, suburbia, female stereotypes, history and the anxiety of influence, etc. -- as the question of our complicity, where it begins, and where it ends, is a constant subtext. Even her installations, which reassemble her production sets such that the viewer must physically enter them in order to access the work, engender this complicity.

Whether she's taking on existing narratives like Kathy Acker's punk classic, Blood & Guts in High School, 1978, and Mike Kelly and Paul McCarthy's infamous work, Heidi, 1992, the latter in collaboration with Sue de Beer, or inventing her own brand of sci-fi tragicomedy wherein prison life and gated communities become petri dishes for psychotic behavior, issues of gender and authorship prevail. Above all else though, its the humor in these works, and the grrlitude that make them so engrossing.

I sat down with Parnes to talk about her work, and its various themes, hoping to get at some of her intentions.

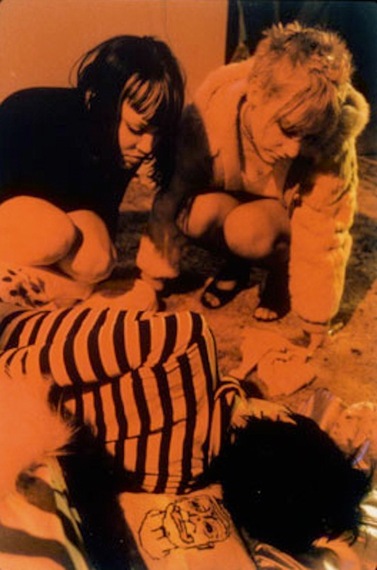

Laura Parnes, No Is Yes, 1998, C-Print, Camera by Laure Leber, Courtesy the artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

JH: The bad girl/teen rebel seems to be a leitmotif, one you simultaneously lampoon through caricature and herald by alluding to its potential. Why do you think this is?

LP: I'm interested in the teenager as an outsider or a symbol of rebellion. There is the romantic vision of the teen peering in on a culture they haven't really personally participated in. This holds potential for criticality but is often tempered by a desire to gain status, power, agency. In Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield is horrified at the hypocrisy of the adult world. Fueled by the cultural ambivalence towards the adolescent female, my teen characters tend to see the absurdity of contemporary culture as a given. Often their access to power requires constant self-objectification and often the power they access is painfully predictable, even boring. What's a girl to do but manufacture drugs or accidentally kill and mutilate your favorite rock star?

JH: Can you talk more about this idea of the "cultural ambivalence towards the adolescent girl" and what you think contributes to this?

LP: I guess I'm talking about our obsession with youth and beauty and our dismissal of young woman in regards to their intellect. And though they become symbols of desire, their pleasure is often of little interest. I'm also interested in the predictable nature of these power dynamics and the clichés and stereotypes that those in power often play out -- like the self-involved, sadistic rock star, the lascivious, judgmental preacher or the condescending, perverse professor.

JH: You've mentioned the influence of Cronenberg's early films, namely his use of architecture, on your work. I can see aspects of that brutalist aesthetic in your sets, and the way they impart a similarly generic sense of menace, and in your attraction to Kathy Acker's novel, Blood and Guts in High School (1978), which you brilliantly adapt in your eponymous film of 2009. Like the authority figures, parents, institutions, etc. that function regularly as allegories of state control, there's a feeling that the built environment is villainous too, somehow. Or implicated. How else do you see this operating in your work?

LP: Blood and Gut's in High School was shot for the most part at Bennington College. The architecture is International style and is very 70's and very New England. In many ways the buildings are stunning but the dirty carpets and stained drop-ceilings are indications of an institution in decline. The vast institutional spaces overwhelm the protagonists always asserting dominance over the students who use it. In County Down, the gated community is a perfect petri dish for Angel's designer drug to go awry. The fake McMansion style exteriors and the cell-like architecture within mirror the characters that inhabit them. It's the perfect setting for an epidemic of psychosis.

Laura Parnes, still from Blood and Guts in High School, 2004/09, Pictured (left to right) Stephanie Vella, Jim Fletcher. Courtesy of the artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

JH: Interestingly, Blood and Guts has none of the burlesque stream-of-consciousness of Acker's writing, its pared down aesthetic and minimal dialogue more like an apocalyptic parable than pomo (postmodern) rant. Of course there's a similar tone, a nihilistic sensibility, that gets evoked, but it still becomes its own work, independent of a viewer's familiarity with Acker's text (a good thing IMHO). How conscious were you in distinguishing your work from its precedent?

LP: I love Acker's work and this book was seminal in the development of my own practice especially how she embraced defiance and her own rage combined with this explosion of intellectual bravado. With her popularity waning and a generational shift away from work expressing anger, I wanted to make a period piece about the current moment - life during the Bush administration. I used certain elements in the book as a starting point and then developed them as a series of allegorical vignettes.

JH: How do you see this generational difference playing out in Heidi II, another example of a work made "after" another (Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy's Heidi, 1992)? And do you consider these works appropriation, critique, exegesis, or just a springboard for your own ideas?

LP: In all of my work that refers to a book, video or film the original texts function as a springboard. There is a book of scripts (published by that Participant Inc.) that include Hollywood Inferno and Blood and Guts in High School, which gives specific insight into how I adapted Acker's book. In Hollywood Inferno it's more just a reference to Dante's inferno. It's Dante as Sandy, an aspiring actress/model traveling to hell on a mall escalator with Virgil the sleazy screenwriter as a guide. Heidi 2 kind of functioned as a critique and homage. It uses humor and B-movie aesthetics to ask questions about gender and the narrative of art historical lineage. There's a bloody puppet birth, bulimic contests, sexual play and technological degradation. It's hilarious.

Laura Parnes, still from Hollywood Inferno (Episode One), 2001/03, Pictured Alissa Bennett. Courtesy of the artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

JH: It is. I particularly love the scene in Blood and Guts where Janie becomes Jim Jones -- archival audio of the later merging with her image as she delivers his infamous speech to the compound. Its such a slapstick moment with perfect comedic timing. A lot of your humor oscillates between this laugh out loud kind of funny and the deadpan. How important is humor to your work, and how do you modulate its role in your work?

Laura Parnes, still from Blood and Guts in High School, 2004/09, Pictured: Stephanie Vella. Courtesy of the artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

LP: I'm very invested in humor and I'm always ironically applying popular culture aesthetics to comment on a lot of other cultural issues. In Blood and Guts the comedic timing is slowed down to the point where one can barley recognize the joke. I'm interested in the tension of pulling a joke apart until it almost disintegrates. When Janie gets thrown in a prison cell and spouts a heartfelt speech about her rights, the policeman responds in a slow motion pivot like Christopher Walken and says "What are you? Some kind of hippy?" I like to play with the familiar and uncomfortable. In County Down, I try to take the teenager embarrassed to be seen shopping with her mother to a new level. Tanya gazes in horror as mom writhes on the ground speaking in tongues and groping a nearby mannequin. The teens cope with a psychotic culture by embracing superficiality to a degree that's nihilistic. In this case, the teens watching the scene respond with a flippant insult about shoes: "P.S. Her shoes are from Target."

Laura Parnes, still from County Down, 2012, (pictured from left to right): Chloe Bass, Patty Chang, Genevieve Belleveau, Emily Roysdon. Courtesy of artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

JH: Yes, there's a wonderfully creepy side to your humor that sometimes has genuinely disturbing undertones. I'm thinking especially of Heidi 2, which opens with the theme song for Rosemarie's Baby, and ends with Heidi1 cramming a TV into Heidi 2's gaping stomach (after the latter has aborted Peter's baby). Its all too absurd to take seriously and yet there are moments of real unease. Many have interpreted the work solely in terms of the anxiety of influence (and you do call it the "unauthorized sequel"), suggesting Grandpa represented Kelley and McCarthy. Others have created a whole psychoanalytic exegesis about it. What were you and de Beer ultimately trying to say with this work?

LP: I can't speak for Sue but I think all those responses are valid. Heidi 2 was fueled by a frustration that work by women tends to be seen in relation to gender whereas art by men is seen in a more universal light. I think this is a frustration that artists feel in relation to race as well. So, for me it's a wickedly satirical piece but also a horror movie, and a sleazy one at that.

JH: Your ongoing series The Real Art World seems to express the same sort of parodic take, reflecting no doubt your experiences as an artist as well as a (former) director of Momenta Art. There's so much that resonates for me having done many studio visits myself, though obviously the scenarios are more outlandish for hyperbolic effect. What motivated you to create this work, and what typically inspires a new episode?

Laura Parnes, still from The Real Art World (Episode 3), 1998-2004. Pictured (left to right): Kel O'Neill, Jennifer Subrin. Courtesy of the artist and Fitzroy Gallery.

LP: I teach and I used to curate and I'm an artist so I've experienced the studio visit from many sides and it's kind of a comedic goldmine. For those who don't know, before a work of art is chosen for exhibition, gallerists or curators visit the artist's studio to meet the artist and see the work in person. Consequentially, the artist must convince the visitor of the value of their work. Like a confidence game or a first date, the power dynamics of the studio visit are wrought with miscommunication and ego clashes. One of my favorite interactions reflects art world characters who eagerly keep the bar low. A painter pulls out a canvas depicting Farah Faucet and says "In this one, really in all of them, there is this question of clichés and stereotypes. I want to make work that is truly cliché. I can't stand work that critiques clichés. I would rather try to find a set of clichés that I can really believe in." The gallerist responds, "That is sooo refreshing."

(To watch episodes of County Down, please visit: http://www.county-down.com/)