This is part 2 of my post on the work of Christine Wilks, the 12th in a series on born digital literature.

Screenshot from Christine Wilks' e-poem "Soma Suture"

Writing is pre-eminently the technology of cyborgs, etched surfaces of the late twentieth century. Cyborg politics is the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly, the central dogma of phallocentrism. That is why cyborg politics insist on noise and advocate pollution, rejoicing in the illegitimate fusions of animal and machine. These are the couplings which make Man and Woman so problematic, subverting the structure of desire, the force imagined to generate language and gender, and so subverting the structure and modes of reproduction of "Western" identity, of nature and culture, of mirror and eye, slave and master, body and mind.

Donna Haraway, The Cyborg Manifesto (1985)

Christine Wilks's literary games harness the bodies of players to create poetic meditations on virtual and embodied forms of existence and memory. Coming from a background in film, she transitioned to digital writing, and is one of several e-lit creators who writes her own code.

You write your own code. How do you think that influences your work? Do you start creating with the code requirements/limitations in mind?

It's a two-way process -- or there are two main approaches I take. I have ideas, then work out how to code them. I have to do a lot of learning because it's usually the case that the new idea I have is just beyond, or sometimes way beyond, my current programming skills or knowledge. Sometimes I have to modify my ideas to what's achievable for me, working alone, at that particular point in time. Or sometimes I shelve projects to tackle later on once I've built up more skills and experience. The other way it works is that the process of learning new programming concepts, techniques or languages (and I love to learn new stuff) gives me ideas which I then go on to make or experiment with. It's often a mix of both workflows. It's an ongoing iterative process of discovery and development.

In his must-read book The Anime Machine, Thomas Lamarre distinguishes "cinematism" and Walt Disney studio animation from "animetism," practiced most commonly in Japan. Unlike cinematism with its Cartesian, bombs-eye view, "animetism is not about movement into depth but movement on and between surfaces" -- that is to say it focuses on the separation of an image into multiple planes. Needless to say, a one-pointed perspective is linked to a unitary, autonomous "I" whereas a multiplanar perspective is consistent with a dispersed, interconnected, gender-fluid subject.

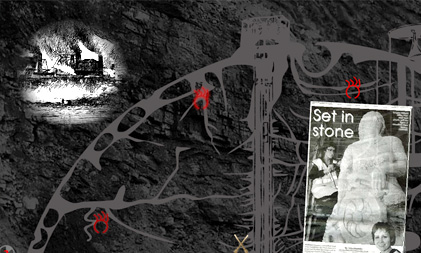

Screenshot from Christine Wilks' "Underbelly"

Wilks's Underbelly is an excellent example of multiplanar storytelling. Composed of layers of image, video, animation and first-person voice-over narration, it relates the history of female miners in England at the turn of the century with the story of a contemporary female sculptor. The sculptor's decision to remain childless to produce her art contrasts with the coalminers "obligatory" pregnancies. Wilks does not judge these two types of creative acts. Instead, she ends the work with a game of fortune where the player, male or female, can decide whether or not he/she wants to have a child, then, spins the wheel of fortune to see what the future brings. Of course, men cannot, as of yet, bear children, and the material limits of the body and body differences are invoked even as they are overcome through the computer interface.

Your earlier pieces are text-based whereas Underbelly is mostly sound and image, can you talk about why you chose to move away from text in that particular piece?

I wanted to try a more cinematic approach -- having had a film-making background -- I wanted to see if it made the experience more immersive for the player/reader. I was also interested in the notion of voice-over, again from film-making, drawing on the tradition in film and TV of the voice-over having authority and an aura of integrity. In a documentary, the voice-over speaks with superior knowledge, and in a fiction film, the voice-over gives the audience privileged information, such as access to the thoughts of the main character or their interpretation of events. I wanted to see how offering playable voices - voices that have to be discovered through interaction - affected that authority and affected the reading. Where does it place the reader/player in relation to the voice, the text? How does it affect the process of identification? Does a playable voice become more authentic or less? That's why, when the voices of the 19th Century women miners are triggered, there's no messing around with them. You have to listen to them without interruption before moving on. I wanted to give those voices of the past more authority than the voice of the artist in the present out of respect for the testimonies of those women.

Initially, I imagined an interface with entirely hidden voices but, because the story has a trajectory that progresses through the voices, there needs to be a limit to the number of times a voice can be played -- i.e. the player has to be able to use up the voiced story fragments so that they feel able to move on (once the narrative system deems they've heard enough). For this reason, I had to provide visual cues -- symbols, icons, illustrations -- that trigger the voices and disappear once they've reached their limit of play times.

Another consideration was to do with the user experience of reading text while sound is playing. I've found that, to be able to read a story or story fragments satisfactorily, the accompanying sound mustn't be too intrusive or insistent otherwise it competes with the reading of text. Often this results in soundtracks being reduced to atmospheric tracks or background music with sound FX thrown in at key moments perhaps, which is fine, but I wanted to explore using sound in a more foregrounded way, as a more substantially expressive component of the work.

It's just another in the vast multiplicity of ways of telling an e-lit story. There are so many options, if I had unlimited time and energy, I'd try them all.

Just as the cinematic, Cartesian perspective eschews alternative views, efficient information transfer aims to minimize disruptive or alternative patterns or "noise".

According to N. Katherine Hayles, "when information is privileged over materiality, the pattern/randomness dialectic associated with information is perceived as dominant over the presence/absence dialectic associated with materiality." N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman (1999).

Wilks' Tailspin invokes both dialectics. Here, Wilks recreates the material world through the immaterial medium of sound--the clinking of china at the family dinner table, the rat-a-tat of machine gun fire, the grumble of an airplane engine.

Screenshot from Wilks' Tailspin

A crotchety grandfather grouses over the annoying, nonsensical beeps emanating from his granddaughter's video game. Preferring his own tinnitus, an internally generated white noise, to the voices of others, the grandfather rejects his daughter's offer of a hearing aid. Through reading the text, the reader learns that, as a fighter plane mechanic in World War II, the grandfather witnessed a young pilot trapped in a fiery plane, burn to death. Now, enclosed in his own little world, he "turns a deaf ear" to the terrors outside.

Memory and history are another key concern for Wilks. Unlike computer memory, human memory is not merely storage and retrieval. It is an act of imagination that depends upon a physical substrate. What does it means when memory is permanent and recall is unchanging or when distance is registered by bit rate and storage location instead of historical time and personal relationship?

Screenshot from Wilks' Rememori

In Rememori, the limits of human memory become a momento mori for the human. Constructed as a matching game, the viewer's own memory skills are utilized to access a poem about a loved one's progressive dementia. In the game, the player chooses the position she will assume: doctor, husband, daughter, father, nurse, etc. As viewers pair terms from mental status tests, for instance, "world" spelled backward, and CT-images of brains, they are reminded that, for better and for worse, mistake, imperfection and variability are an intrinsic part of our embodied existence.