Pat Passlof's writing --provided by The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation--points time and again at how significant the late 40's and early 50's were for her. Charlie Egan Gallery's 1948 Willem de Kooning exhibition provoked Passlof to track down the inspired painter. She pegged, by premonition, Black Mountain College as the most likely place to find him. This gambit paid off with de Kooning arriving as a last minute replacement instructor and by the fall of '48 Passlof was studying with him privately in a loft he arranged for her on 10 street.

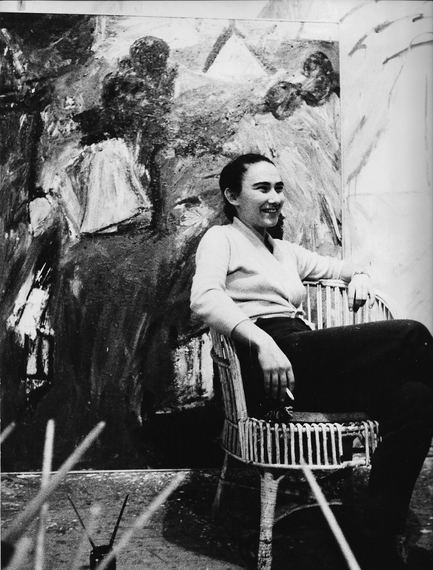

The idealistic 20-year-old must have experienced a kind of vertigo plopped into the ferment of the lower Manhattan artist community. Therein, quickened by connecting with her kindred spirit/mentor and this, "...period... full of high feeling [and] inspiration for all..." she began to pursue the life of an artist. She would have been one of (if not the) youngest artists on the block, and by chance was likely the very first artist to live and work on 10 street. Eight years ago as an undergraduate I studied with Passlof, it was a unique experience, and I'm happy to see her work from the 50's currently exhibited at Elizabeth Harris Gallery where we are presented with an intimate and possibly fundamental perspective in the trajectory of 20 century American Art.

The majority of her work from the 40's was lost to a fire. The consequent gap in her oeuvre frames the first half of this exhibit, which engages her efforts in media-res. She is, by the early 50's, fully contending with the "...world of artist concerns..." introduced by de Kooning and the eclectic cadre of artists in the downtown enclave. These paintings grapple with those incipient artistic concerns. At a time when formal conceptions for abstraction were inchoate, Passlof's painting, still connected to its artistic feelers, strikes a variety of chords.

Though achieving differing degrees of success these images provide complex visual experiences and often compelling conclusions. There is the sense of arrival following extended interrogation: How and what does it mean to paint and make pictures? This imperative seems to emerge from -- and continue into -- the paintings themselves where themes and painterly affects transform in their role and countenance. Passlof is testing, tasting and discovering a range of expressions as yet uncongested by the onslaught of superficial simulacra that followed the popular successes of Abstract Expressionism.

Serendipitously, this exhibit is coincident with an upswing of interest and criticism in painting. Passlof's images are antithetical to the generic formalism described in Jerry Saltz's Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same? and play an illustrative counterpoint to some of the issues discussed in Noah Dillon's The Zombies: Contemporary Abstraction and its critics. Everyone loves zombies. These paintings are not sofa-warmers, they have good legs and renew with close looking. The phenomenological realm that they inhabit is resistant to codification (and of course challenge description). In this, they also underscore the long-standing issue of art that lends itself to the form of art journalism or attractive gallery announcement.

There are significant transitions within the span of the exhibit. A dramatic example is seen between the direct, vigorous and densely interlocking forms of Panoras (1954) where we see Passlof telegraphing out from de Kooning's early 50's abstractions and a later painting, Lookout (1959), which may represent the most fundamental leap in her approach here. The forms of Panoras press out to the edges of the canvas, closing up the dimensional allusions, the spatial recesses or background, that de Kooning never really ceased to employ. By this, it asserts the surface, the veracity of its paint handling and brings to bear its formidable physicality. It leans in and envelops the viewer in an intensity of closeness.

In Lookout, Passlof works with a hyper-normal sensitivity, expanding, lifting and connecting the luminous flight of space in this large canvas with parsimonious and energetic brushwork. Each mark feels felicitously placed, arrested before the effects of the image can collapse. It is as if the denseness Passlof utilizes to establish the dynamism of Panoras has looped upon itself and found the poetic charms of a bird's flight in loose but exactingly felt touches; the bodybuilder's pose versus the lightness in the dancers leap.

Influence plays an unmistakable but evanescent role here. The catalog essay, by Raphael Rubinstein, does well to point out the dialogue between Passlof and her husband Milton Resnick as perhaps the longest continuous artistic dialogue of the century. The quality of these images rebuts conventional assertions whereby artists' of the period were set out to simply undermine canon or observe metaphorical fratricide as a right of passage. Instead, the risks taken are those of conviction. Passlof takes a stand, and deals with the disarmingly uncynical philosophical issues that emerged from abstract painting, now long since accepted for granted; as she notes: "...no-one knew if abstraction was even possible...".

At her best, Passlof's paintings resonate in the rise and remission of tensions that ultimately settle -- buoyed with the absoluteness of a child's wonder -- in a wash of uncommon sensuality. They reckon with the forces that animate the vitality, or at least addictions, of so many painters. Passlof isn't mentioned in most reviews of the period. Her early achievements going unnoticed or failing to form well with the tools of writers since. These paintings exhibit a complex plurality and emerge as unique subtleties. They offer an experience. It's difficult to image an expanding venue for such triumphs of subtlety in an art world engorged by feel-a-like, market-framed tokens.

A half-century past, Passlof's paintings still probe the most salient question in art; the question of meaning.

- Out of the Picture -- Milton Resnick and the New York School: Geoffrey Dorfman, Midmarch Arts Press 2003 - Passlof quote

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Pat Passlof: Paintings from the 1950's: Raphael Rubenstein, Elizabeth Harris Gallery 2014