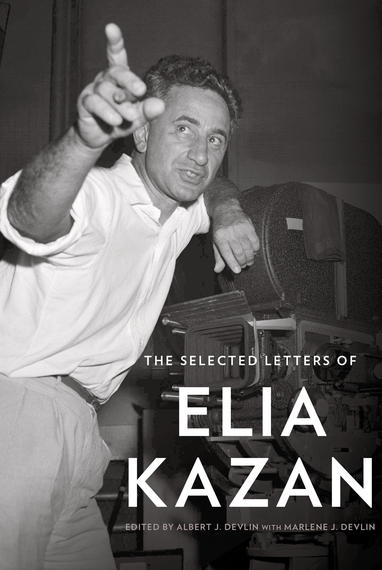

Elia Kazan directed virtually back-to-back the greatest American dramas of the twentieth century--by Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams--and helped shape their future productions. In The Selected Letters of Elia Kazan, edited by Albert J. Devlin, we see how Kazan collaborated with these and other writers: Clifford Odets, Thornton Wilder, John Steinbeck, and Budd Schulberg among them. The letters give us a unique grasp of his luminous insights on acting, directing, producing, as he writes to and about Marlon Brando, James Dean, Warren Beatty, Robert De Niro, Boris Aronson, and Sam Spiegel, among others. We see Kazan's heated dealings with studio moguls Darryl Zanuck and Jack Warner, his principled resistance to film censorship, and the upheavals of his testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. These letters record as well the inner life of the artist and the man. We see his startling candor in writing to his first wife, his confidante and adviser, Molly Day Thacher--they did not mince words with each other. And we see a father's letters to and about his children.

An extraordinary portrait of a complex, intense, monumentally talented man who engaged the political, moral, and artistic currents of the twentieth century. I spoke with Devlin about the book.

How did you become interested in Elia Kazan?

My interest in Elia Kazan is longstanding. I was born in 1942 and reared in central New Jersey. By my mid-teens I was an avid reader of fiction and also aware of a theatre world a proverbial stone's throw away in Manhattan. Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan were dominant figures, fixtures, if you will, in the newspapers that I read, with theatre reviews by Brooks Atkinson in the Times and Walter Kerr in the Herald Tribune. Williams in particular intrigued me, if only because his life differed so radically from my own as the offspring of a rather conventional family of the 1950s. My general research interest in Southern American literature developed in graduate school and led not surprisingly back to Tennessee Williams. The opportunity to edit his letters for New Directions completed a circuit of sorts and again, not surprisingly, led to Elia Kazan. Research for volume two of the Williams letters entailed many visits to the Wesleyan University Cinema Archives, where Kazan had deposited his papers before writing his autobiography, A Life (1988). I read both sides of the Williams-Kazan correspondence and harbored a thought that the latter's correspondence would complete another personal circuit. Kazan's letters to Williams were compelling if only by reason of the way they illuminated the vexed issue of the author-director controversies that surrounded the production of Cat on a Hot Roof and Sweet Bird of Youth to a somewhat lesser degree. But the Williams-Kazan letters were only the tip of a much larger and diverse collection of Kazan correspondence held by Wesleyan. I was hooked by the vibrant voice and the historical riches I found in the letters and in 2005 wrote a series of my own letters that led eventually to The Selected Letters of Elia Kazan, which you graciously plan to review.

Many other biographers and indeed his own film America, America suggest that his upbringing and the Hellenic Diaspora shaped many parts of his life. His letters suggest otherwise as well as a forceful personality, often at odds with the one commonly portrayed. Do you think his letters paint a true picture or was he, even in them, putting on a mask of sorts?

In early correspondence with Cheryl Crawford (Fall 1935), one of the founders of the Group Theatre, Kazan described himself as "carefully impulse-broken" in his youth by a domineering father. He signed the letter "Gadg," the diminutive form of his well-known nickname "Gadget," which became a trademark of sorts, as well as a measure of his utility. Much later, in a letter to John Steinbeck, he deplored the "ever-ready compliance" and "adaptability" suggested by "GADG" that had made it "possible" for him "to be the 'necessary' thing to any man" (August 27, 1960). There were other "fathers," if you will, authority figures at once inspiring and demanding, encountered by Kazan in theatre: Harold Clurman, Boris Aronson, and especially Lee Strasberg. And there were such overarching collaborators as Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, whose drama Kazan "interpreted" in what he knew to be "a Playwright's medium" (6/6/1955). In film a studio system, enforced by Darryl Zanuck and Jack Warner, with whom Kazan worked under contract from 1945 until the 1960s, demanded adherence to the economic laws of the industry, predicated upon the satisfaction of a mass audience, and further hedged by the Production Code Administration and the Catholic Legion of Decency, powerful censors of the day. Kazan claimed, again in correspondence with Cheryl Crawford, that he knew from the first what he "wanted" and "early determined never to accept anybody's estimate" of himself (summer 1934), but in fact he worked in highly restrictive media, and with authoritative figures, for the majority of his productive years. (Novel writing, which engaged Kazan in the later decades, was a welcome antidote.) Just as often as the letters express a "forceful personality" that strenuously advised revision of classic texts or challenged censors, they also show flashes of deference (especially to John Steinbeck), unusual patience (with Tennessee Williams), conciliation (with Lee Strasberg), and strategic flattery.

Who is Kazan? one might ask, the "forceful" director of theatre and film or perhaps the acquiescent son of an immigrant family (hence an "influence"), whose success was a matter of deft maneuvering. Well, in the preceding paragraph I have tried to give personal and professional context to the several "Kazans" that appear in The Selected Letters. Their interaction, I think, is less a consequence of wearing "masks" than living in real time, which "letters" are well positioned to express and preserve. What is it, then, that drove Kazan into singularity of intention if not his determination to become "A SINCERE, CONSCIOUS, PRACTISING ARTIST." This formative desire, stated to Cheryl Crawford in 1935, when the Group Theatre found little promise in Kazan's acting, saw the future director and screenwriter through the inherent strictures of Broadway and Hollywood, through difficult collaborations, especially with Tennessee Williams, through periods of exhaustion, depression, and futility, through the historical and political misfortune wrought by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and through marital woes. The goal of artistic independence was finally realized in writing, casting, and filming America America (1964) on location in Turkey and Greece, Kazan's second homeland.

Insofar as "influences" on direction are concerned, Kazan dismissed "deep and dark inspiration" in preference for "a definite something--the experience of the artist--what he's felt, known, remembers--in short experienced" (fall 1935). It's not a divisible or neatly segmented entity but the sum of a life.