Our eyes are far too good for us. They show us so much that we can't take it all in, so we shut out most of the world, and try to look at things as briskly and efficiently as possible.

What happens if we stop, and take the time to look more carefully? Then the world unfolds like a flower, full of colors and shapes that we had never suspected.

In this column, I am going to be pondering how we see the world. I will be describing how to look at paintings, photographs, and sculptures (that is my field, art), but also grass, sand, twigs, sunsets, Egyptian scarabs, discolored porcelain teeth, cheddar cheese, viruses, X-Rays, spectra, fingerprints, candle flames, galaxies, graphs of bird song, engineering drawings, ice halos behind palm trees, the lines in an elderly face, the ripples of muscle in a shoulder, the logic of crystals, the colors in a rainbow, the shapes of culverts, the species of mirages, the faint lights in the night sky, the zig-zag patterns on moths' wings, the engraved designs in postage stamps, the things you can contrive to see inside your own eyes.

What I have in mind is a series of lessons about how to use your eyes more concertedly, with more patience, than you might ordinarily do. It's about stopping, and taking the time to simply look, and keep looking, until the details of the world slowly reveal themselves. I especially love the strange feeling I get when I am staring at something, and suddenly I understand: the object has structure, it speaks to me. What was once a shimmer on the horizon becomes a specific kind of mirage, and it tells me about the shape of the air I am walking through. What was once a meaningless pattern on a moth's wing becomes a code, and it tells me how that moth looks to other moths. And paintings show me more each time I look; there is apparently no limit to what they can mean.

My opening example is Mondrian.

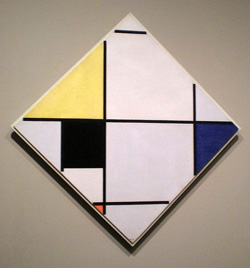

Specifically, one of the Mondrian paintings in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, across the street from where I work. It is called Lozenge Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red, and Gray and it was painted in 1921. It's a simple picture: off-white, with black stripes and four color areas: black, blue, pale lemon yellow, and a touch of orangey red. At least that's what I thought before I had looked closely at it.

Specifically, one of the Mondrian paintings in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, across the street from where I work. It is called Lozenge Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red, and Gray and it was painted in 1921. It's a simple picture: off-white, with black stripes and four color areas: black, blue, pale lemon yellow, and a touch of orangey red. At least that's what I thought before I had looked closely at it.

I have occasionally taught a course in which students copy paintings in the museum. The course was open to anyone, even students who had never painted. The only requirement was bravery, because it turns out that when you put up an easel and canvas in the museum, everyone talks to you. They give you advice and criticism, and they aren't always polite. One of my students was harangued for choosing to paint a nude, "even though," as the angry visitor said, "you're a woman yourself." Another time, a guard asked me if I thought my student was worthy of copying a small painting showing Moses crossing the Red Sea. "Do you think your student believes the Bible story?" the guard asked. I said, "I don't know, but do you think the painter believed in the Bible?" He said he wasn't sure, and he'd get back to me. The next week, he said he'd decided the painter was an atheist, because the painting didn't have enough thunder and lightning in it--it wasn't dramatic enough to ring true. (I think the guard was thinking of the movie "The Ten Commandments.") After that, the guard left us alone: he decided that a non-believer could copy a non-believer's painting, but he just wasn't interested in the result.

When one of my students asked to copy that Mondrian, I said it might not be very rewarding, because it was so simple. It turns out I was very wrong, and since then I've had three students try to copy the painting. It's a very difficult and complex image, masquerading as a simple abstraction.

If you step right up to the cordon, you'll see that Mondrian changed his mind about whether the stripes should go right up to the edges of the canvas. He painted out the ends of the stripes, so that they appear to stop where the canvas stops.

(All photos: author.)

He wasn't especially careful with his repainting, which is a clue to how closely he expected people to look. Art historians have noticed his change of mind, and it has been said that before the early 1920s, Mondrian thought of his compositions as part of an infinite plane, which could go on indefinitely in all directions. Starting with paintings like this one, the canvas is the whole object, the whole universe, and there is nothing beyond it.

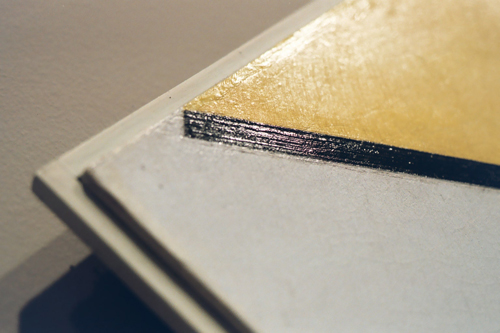

If you bend down, and look up against the light--often a good trick in museums, because it reveals flaws and shows off the painting's surface--you can also see that Mondrian painted the black rectangle with thin paint, so the warp and weft of the canvas shows through. (The warp and weft are at forty-five degrees to the stripes, because the stretcher is rotated.) The yellow area is painted much more thickly.

An even closer look at the yellow shows how luscious the paint surfaces are, some ribbed, some rubbed into the weave. It's also possible to see how Mondrian smoothed the edges of the yellow region, creating a glossy painted frame.

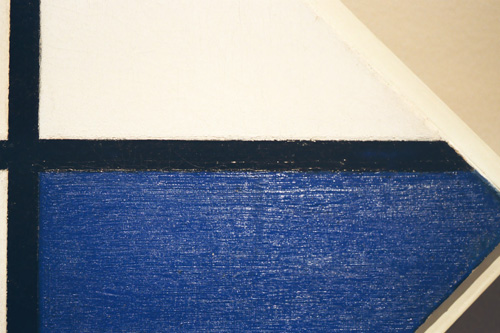

Each surface and stripe has its texture: the stripes are scored with little ridges, and some of the surfaces, like the blue area, show those freehand back-and-forth brush textures house painters try to avoid. Altogether the painting is rich in surface textures, what art historians call facture.

My student tried hard to get the thick furred look of the blue area, but all he could manage was a flaccid, watery pool of blue:

So far none of this is new to art history, and there have also been some very careful analyses of the ways some stripes go over others, and how Mondrian built his paintings into a kind of woven bas-relief. (There are excellent accounts of this by Yve-Alain Bois and Harry Cooper.) But it is not difficult to go beyond what has been discussed in art history.

If you look very closely at the borders of the stripes, you see they aren't just lines where black meets white or blue or yellow. The edges of the stripes are rough. It is known that Mondrian painted his stripes by laying down strips of paper, the way decorators and contemporary painters use masking tape. But that produces a clean border, and the borders in this painting are messy. Unfortunately, with the naked eye it's hard to see exactly what makes them messy.

I have two devices to me solve mysteries like that: a camera with a macro lens, and a pair of surgeon's glasses, which are heavy metal frames with little binocular telescopes mounted on them. The little telescopes are amazing: if I stretch my arm out in front of me, the telescopes focus on one-quarter of one of my fingernails. (The surgeon's glasses are also embarrassing to use, because they have a kind of dorky mad scientist look. My student and I got lots of odd stares while we were inspecting the painting.)

In this photograph, taken with my macro lens, my student is trying to reproduce the complicated marks at the border of one of the stripes. (He is wearing plastic gloves to protect himself from the toxic chemicals in the paint; some painters prefer the old, poisonous solvents and pigments to the new healthier materials.) He is painting freehand, without a paper strip to help him, because he thought that is what Mondrian did.

A closer look at the original shows that Mondrian did put a paper strip down, and he painted over it to get a sharp edge: but then he removed the strip, put another one down in a slightly different place, painted over that one, and so on, creating a kind of little stairway of paint.

In other parts of the painting, Mondrian clearly painted freehand, with no paper to guide him. On one place, it's possible to see how he painted vertically, carefully edging up to the stripe. To see that, look very closely at the bottom edge of the stripe in the next photo, about an inch to the left of center.

My student and I studied that, but again his copy failed, because he couldn't get just the right texture of paint--Mondrian's paint was sticky, and the bristles on his brushes were stiff. My student ended up with an ugly ridge of paint:

In some places, Mondrian painted parallel to his stripes, trying to keep his hand from wavering. In other places it seems he enjoyed the slight tremble and wander of his hand. There is a lot to see in this last detail: underneath the stripe, you can see where Mondrian carefully edged his brush up to the stripe, overlapping some horizontal marks he'd made freehand. Over the stripe there is a thick hedge of short marks, all freehand, intended to give the stripe a rich, entangled margin.

You don't see any of this from two or three feet away, and it's clear Mondrian expected his viewers to stand back so they wouldn't see things like the sloppy way he truncated the ends of his stripes. But you are aware of a richness, a shimmering effect, a depth. The paintings are three-dimensional. The paint has visible gestures, it is human, it moves. In the language of art history, it is painterly. It belongs to the tradition of Titian and Rembrandt and Delacroix, and not just to the asceticism and idealism of the early twentieth century.

In the Art Institute of Chicago, as in many museums, the Mondrians hang next to other paintings of the time, also geometric and abstract. In comparison to their resolute, sterile flatness, Mondrian's paintings have depth. They speak to the deeper history of painting. It's true Mondrian is forbidding, ascetic, pure, impersonal, ideal, clear beyond the mess of an ordinary life. But it is also true that he was thinking of Old Masters, and of what paint could do. He just kept the poetry so tightly reined that it is nearly invisible.

Perhaps it requires a slightly abnormal sort of seeing to notice all this--geeky doctor's glasses, an expensive camera lens, a student who is willing to fail while people watch. But once you have seen how the painting works, Mondrian will never be the same.

I know there are many questions lingering here. What is close looking, exactly? What happens to the experience of the artwork when you look very slowly? It seems artificial or unnatural to look closely: after all, it runs against the grain of today's very distracted, fast-motion seeing. And yet poets do it all the time: close reading is part of good reading.

I am up for all those subjects, and more. I hope this column will inspire you to stop and consider art more closely, but also to see all sorts of things that are absolutely ordinary, things so clearly meaningless that they never seemed worth a second thought. Once you start seeing them, the world--which can look so dull, so empty of interest--will gather before your eyes and become thick with meaning.