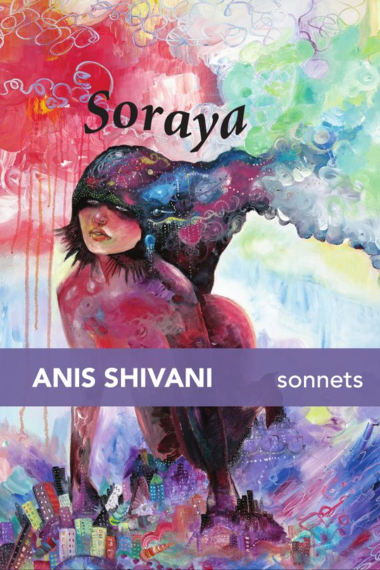

My book of 100 experimental sonnets, Soraya, which will be released on June 7, 2016 by Black Widow Press (publishers of contemporary poets like Clayton Eshleman, Jerome Rothenberg, and Robert Kelly, and of the classic surrealist texts), was a breakthrough in my poetic journey. In my mind, there is a before Soraya and an after Soraya, a clear dividing point which freed me of many expectations I had of writing poetry.

In the very beginning for me were people like Neruda and Paz and Auden and Adrienne Rich, but this goes back a very long time, almost twenty years ago, in college and shortly thereafter when I was struggling, all on my own, to find my voice as a poet. We are talking about the mid to late 1990s, when the world was almost becalmed, compared to the hyperaccelerated turmoil we've moved into now. It was a safe and comforting--even a lulling--home for me in Cambridge, Mass., as I labored as a development economist at the National Bureau of Economic Research, writing poetry (and Borges-influenced short fiction) in the shadow of Martin Feldstein, he who wanted to--and perhaps still does--end social security.

Nothing against Marty, a popular Harvard prof still, because that setting provided just the right ironies to give me my start. I would stay at my office until dawn, and leave for home on Prescott Street shortly before the early-rising economists made their way over. I wondered all the time at the marvel of the apparently self-sufficient, engrossed-in-itself world going its own way, in the bustle of Harvard Square, in the rest of Cambridge and Boston, in New York and D.C., so much turning of the wheels, so much aspiration and ambition and ego, yet everyone, once you probed even a little, turning out to be a mass of vulnerabilities and insecurities.

Writing made the world seem all the more unreal to me, which I think is the ultimate addiction of writing, the reason why we writers want to keep doing it no matter the costs it extracts, if we're serious enough, on our health and finances and family and social life.

Those who come to writing--and art in general--have always felt like outsiders, typically from the youngest age, and writing or art then becomes a tool, at a later age, to put the world in its place, so to speak, or to make sense of it (or nonsense of it) in a way that one's wholeness is magnified, one's sense of solidity and balance and belongingness are regained. The world, during this entire process, remains on the outside, in fact one's feelings of being a stranger in the world only escalate. But here's the difference. As an unthinking young person or even as an adult, without the arsenal of writing or art, one's strangeness is debilitating. As a writer or artist, that strangeness is enhanced, intentionally so, and becomes a powerful tool to expand one's understanding.

And it is poetry, or poetic language, or poetic sensibility, or poetic awareness, that expands this consciousness more than anything else. I've always claimed that the novel has the most important claim on consciousness-raising, I've often said that once one writes and publishes a novel, one is not the same person anymore. And each time one writes a novel, this happens, the mind expands, one leaves the old self behind and becomes someone new. But I think I can reconcile these apparently contradictory claims by thinking of successful novels as experiments in poetry, sharing with poetry an outlook of newness and intentional strangeness and raw disinterestedness that leads to strange new insights about the ordinary world, just as poetry does. In a sense, one can think of the novel as an extended poetic metaphor, one stretched out to a few hundred pages, but like a poem, if it is any good at all, consistent throughout, from the first sentence to the last, having the same voice, the same impulse to destroy and rebuild and destroy and rebuild the metaphor again and again.

As I was saying I started off writing bad Neruda-influenced poetry. In that strangely pacified world of 1990s New England, it took an effort to be political, especially to be political in one's writing, but it seemed to me that that was where a breakthrough in poetry was needed. Much later, when my first poetry book, My Tranquil War and Other Poems, was released (about five years ago), I realized that I had been trying all along to discover a lyrical idiom to express what was happening in the public sphere, to notions of citizenship and virtue, obligation and identity, technology and purity, freedom and repression, in the context of a globalizing world, a post-cold war world that was beginning to take shape but hadn't yet emerged full-blown.

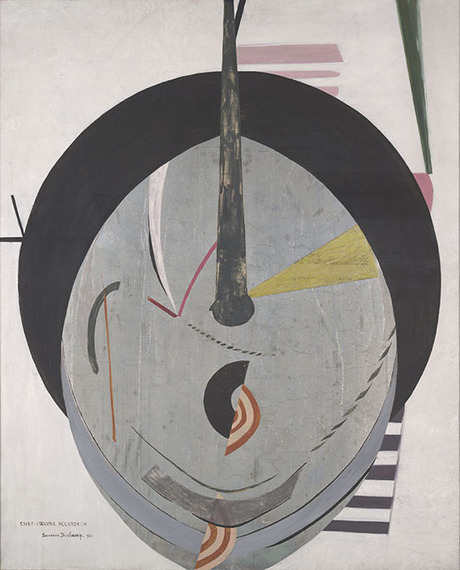

Suzanne Duchamp, Chef d'oeuvre accordeon, 1921, at the Yale University Art Gallery; this is the cover I plan to use for The Moon Blooms in Occupied Hours, an image that also features prominently at the gallery's current exhibition "Everything is Dada" (February 12-July 3 2016).

I wrote that kind of poetry for a decade, and My Tranquil War was the distillation--of at least five books worth of poetry--of these efforts. I engaged lustily with the artists and filmmakers and musicians and writers who had inspired me, and whose own idioms (most typically expressed in various forms of modernism) had meant all the world to me as I went about formulating my own language to address the realities of the contemporary political world.

Once My Tranquil War came out I realized that I was finished with that kind of poetry. I wrote a couple of transitional books, essential in their own right for my growth--The Moon Blooms in Occupied Hours and Whatever Speaks on Behalf of Hashish--and then completely moved on to a new territory of freedom, writing idiosyncratic, dream-based, naughty, afterthought-like, technological, ferocious, writerly, absurd, love-like poetry. I could call it surrealist, but it isn't quite that, and it does not fall into any of the established genres of so-called "experimental" poetry today, language poetry or the many deviations that have become popular. In essence, by writing Soraya--in the spring of 2013--I made my previous poetry, my previous writing practice, strange to myself, intentionally strange and awkward.

Portland artist Jahna Vashti allowed me to use her painting, Before She Knew, for the cover; I wanted an exuberant female image, a representation of the muse (Soraya) dominating the landscape of consciousness, and thought this image fit perfectly.

Soraya freed me because finally, after a lifetime of struggle, I gave up many obligations one, unfortunately, feels as a writer: to be true to oneself or one's own reality (but what is truth anyway, and why should truth be a value, why not lies, for example?), to make sure that one has acquitted oneself well as a human being on earth living among other living creatures (but doesn't death invalidate this purity of spirit?), to say what one needs to say in a language that's truly original and real and authentic (but was there ever a more delusional search than to discover authenticity?). And on and on. I think that as soon as one goes into writing expecting to deliver something--something concrete and real and substantive and original--one is asking for trouble.

Writing comes from writing. Or rather, writing comes from the reading of writing, others' writing, one's own writing, all the potentialities of writing one senses have escaped others and oneself. Writing is its own greatest reality, the only fact and spirit and value it needs to contend with, all else is irrelevant. Anything else just gets in the way. Paradoxically, of course--and anything that means anything in art always turns out to be a paradox--one discovers everything that exists outside writing by conceiving of writing as strictly within writing. The way out is to go all the way in (inside writing, that is, not inside a self determined early on to a great extent by outside forces), but one can never have a view on the outside by looking directly outside.

I go back to my office at the NBER in Cambridge, my first writing cubicle, the first room of my own (well, at least from 10 pm to 5 am), where the question of authenticity and originality was front and center on my mind. In a flood of so much propaganda and indoctrination (I left academia, and the Boston/NYC/DC bubble, precisely to escape that), what constitutes one's original thought? Did I even have a single original thought in my head, though I liked to think of myself as unusually rebellious and freethinking, after years of formal education? Most interestingly, with so much writing already in the world, how does one go about producing original writing? And were these the right questions to ask to begin with?

Again, I come to a paradox. Soraya can be seen as the result of a long process of thinking about the question of originality. Yet I fell in love with unoriginality. Unoriginality--or what seems to ordinary modes of perception as such--is actually the way into originality, to the extent that such a thing exists. One can only be original by being unoriginal. But again volitional unoriginality is different than the unconscious state with which one begins. And this goes back to writing coming from writing, by which I mean Soraya as an extended illustration of poetry coming from poetry, or rather poetry coming from accumulations of words, or musical components, words as fragments of music and interesting sound.

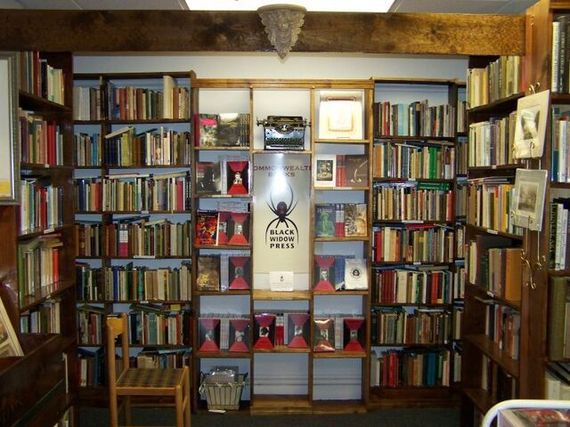

Joe Phillips and Susan Wood, publishers of Black Widow Press, also own rare and antiquarian bookstores in several cities, one of which is Crescent City Books in New Orleans, newly relocated to 124 Baronne Street.

At one time the title of Soraya used to be Dictionary of Soraya, which of course was too revealing. Nevertheless, "dictionary" has a special meaning for Soraya, and for the four books of poetry I've written in the last year, which flow from Soraya's aesthetics but take it in four distinct directions.

We are often fearful of dictionaries. Why? Because they shed light on our ignorance of the origins of language and the usage of words? Because they make us feel stupid, or marginally less so each time we look up a word? Because dictionaries are overwhelming in their comprehensiveness, as though to say, this is all of language, a given language, in one place? Because dictionaries present a false view of the beginning, middle, and end of a language, as though we'd already reached the end of the story? Because dictionaries break apart words, expose them to light, and therefore alienate us from words we may be familiar or intimate with? Because dictionaries are compendiums of false knowledge, the prescribed ways that words should be used, in certain contexts and sequences and not others? Because they reduce us as humans, reduce our infinite complexities to matters of form and decorum and protocol?

In Soraya, for the first time in my poetry writing, I broke free of decorum. Surrealism, in the classic understanding, meant putting things together in ways that were unexpected or surprising or free of "sense." I think of Soraya, rather, and the poetry books that have followed for me, as putting sense back into dictionaries. And I don't just mean dictionaries of words, but dictionaries of identities, dictionaries of histories, dictionaries of geographies, dictionaries of progress, dictionaries of psychologies, dictionaries of nations and families.

In essence, Soraya is a dictionary; but without the gross insincere invitation most dictionaries offer anonymously to anonymous personae. It was a long and winding road from Paz and Neruda to the selfhood of dictionaries (meaning my own "unoriginal" selfhood), but I think the original impulse always formulates the only end one cannot foresee, the thing one started with becoming its opposite yet true realization.

Soraya's book release party will be held at Houston's independent Brazos Bookstore on May 24, with Fran Sanders, director of Public Poetry, moderating a discussion on avant-garde poetics, and audience reading of select Soraya sonnets.

Three Soraya sonnets:

80.

The fields of Iceland spar, as maladjusted

as the I Ching, make-work leechcraft to

end the legal fiction whereby I holiday in

your jujube craft: Soraya, jacquerie we

performed upon leaving Rumi's jailhouse

has come back to haunt knitting-machine

dreams. All I know is Leda's learned

helplessness, Key Largo's kilobits of

ketene IP addresses. Ipsissima verba

League of Nations poison, glass free of

economic indicators, Soraya's recitative

recollection of codes of sickness, and

shuttle diplomacy our soigné imitation of

the valetudinarian spandex squirearchy.

(Originally published in Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review)

41.

Visions of the louse, lotus-eater in Louvre,

midinette's MIDI the missing link to your

mistrial, Soraya, destructive halogen truth

burdening my Recife recollections: squaws

looking for square meals in the thunderous

textbooks of erotology, dust-delivered

atoms of mise en scène where playboys

reach secretariats of intelligence, wounded

by rabbit's foot. Rabbinical quipu, our

quintet of hermit crabs taking over the

ghat leading down to ghibelline ghetto,

Soraya, we all cheat on the exacta, propped

up by the dry misericord, package tours

ending in nightly finger-of-god juju.

(Originally published in Cordite Poetry Review)

28.

The wedding of hive bees, HIV-positive doxy,

Soraya, draft dodger to dozens of souteneurs,

is nothing like our down-to-earth draggletailed

doxologies. We pair paintboxes paid

for by Pahlavi's pains, paladins of paleopathology,

rich like jinrickshas riding up

rift valleys in the Sierpinski triangle: sigil

as significant as Shiva's situs inversus

after the first sitz bath. Do you remember

data gloves? Darkling beetles obscure the

age of racism for Dasein dashing about.

Soraya, dare me to swim the Dardenelles,

my date of birth is suspicious susurrus,

hardly a punctilio on the swage block.

(Originally published in Volt)