Almost as quickly as it arrived and changed our world, Postmodernism promptly disappeared.

But with a new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, it's time now to take a look back at its evolution from provocative architectural movement of the early 1970s -- one that challenged the orthodoxies of modernism -- to a cultural shift that affected the direction of art, film, music, graphics and fashion.

"Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990," curated by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt will be the first in-depth survey of postmodern art, design and architecture, and will open on Sept. 24.

I had the opportunity recently to interview Adamson about the significance of the movement and its impact on our world. His responses are below.

Why was postmodernism important?

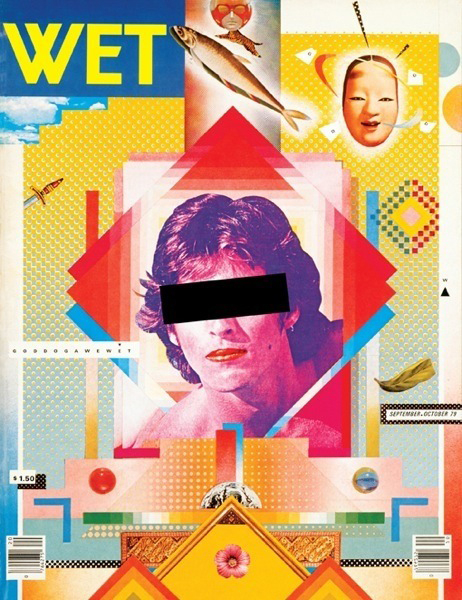

I would define postmodernism as a set of radical strategies that emerged in the 1970s, but proliferated rapidly especially in the early 1980s, which had in common an antipathy to modernism and sought to depart from its certainties, progressive narratives, and claims to objective quality. In place of these values, postmodernism offered historicism, self-referentialilty, bricolage, and in general, a freedom of choice in design. It's useful to distinguish postmodernism from post-modernity -- the latter, according to writers like David Harvey and Fredric Jameson, being a cultural condition associated with advanced capitalism. Postmodernism, by contrast, is the critical artistic response to that condition.

It's also worth mentioning that popular culture (especially music and other performance) was an effective distribution system for postmodern style and ideas -- in this case, you have not just a situation of radical poses influencing vernacular culture, but a more complex interaction between performers and their subcultural fans. New Wave music in general is a good example of this, as is hip hop. This is one reason we have included this material at the heart of the exhibition.

By the late 1980s there was exhaustion around the term -- for lots of reasons, of which perhaps the two most important are: the simplification of the idea, so that it seemed to be merely ironic or negative, rather than expansive and liberating; and the corporate use of postmodern imagery and techniques as a form of marketing. The end of our show tracks this development, framing 1980s postmodernism as a contest between critical and commercial strategies. Because this conflict came to seem a stalemate, by the 1990s critics, theorists and artists of all kinds wanted to move on, and did, sometimes into a neo-modernism, sometimes into the new possibilities afforded by the digital. Returning to the topic now, though, affords an opportunity to re-evaluate it and for younger audiences, see the original ideas and works of postmodernism for the first time.

When did it commence? Was there a watershed moment? A symbol?

You can find lots of beginning points -- we show a few in the exhibition, including the destruction of the modernist Pruitt Igoe complex in St. Louis, in 1973. This failure of a rationalist housing block was adopted by Charles Jencks in his book The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (published 1977) as an example of a destructive act that made it very clear a new set of ideas was needed. As he put it modernism was dead, so "we might as well enjoy picking over the corpse." We also look at Italian Radical design, as exemplified by Alessandro Mendini and Ettore Sottsass; and the interest in the billboard-like facades of Las Vegas casinos among architects in the late '60s, notable Denise Scott Brown and her partner Robert Venturi. A notable turning point in the proliferation of postmodernism was the first Memphis collection, shown in Milan in 1981, which was widely distributed in visual form through magazines and was influential on a huge range of interiors, furnishings and even personal accessories like jewelery.

When did it end? Why?

Though the effects of postmodern provocation are still with us, we end in 1990 for a few reasons: the incipient rise of digital design, changes in the political-economic landscape (with Reagan and Thatcher's departure, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the 1987 stock market crash all within five years of one another) and also an exhaustion with the term postmodernism. It had become a corporate style instead of a radical one by the late 1980s. As David Byrne put it in his essay for our exhibition book, "it became a look -- time to move on."

Who were the leading proponents?

In addition to the ones I mentioned above, Byrne and Grace Jones are good examples. In their work you can see how conventional individuality is replaced by the more assertively artificial, acutely self-aware use of the garment as one element in a palette of provocative, sub-culturally charged but elusive style statements. Also Laurie Anderson, for her amazing synthetic persona.

How did it manifest itself?

Many ways! Fashion, architecture, graphics, the crafts, product design, fine art, you name it. Postmodernism lived up to its claims of frictionless speed by infiltrating almost every corner of art and design practice.

What was the philosophy behind it?

Hard to summarize, but if I had to point to one idea it would be the emphasis on the image over substance. Style (or maybe stylization) becomes an exquisitely self-regarding thing; the photo is more important than the object; performers are always thinking about the performance, as well as the content.

At one point in architecture, there seemed to be a struggle between postmodernism and deconstructivism for the future of architecture. What was the result and why?

Yes, that's true -- deconstructivism, as practiced by Tschumi, Libeskind, Gehry, Hadid and Eisenman, is introduced as a way to reclaim modernist formal experimentation rather than embracing the historical and vernacular, as postmodernism did. The result of this, as you might expect, was a conflation of the two -- I think you can look at most contemporary architecture as informed equally by decon and pomo, with the former providing an intellectual basis and the latter an expressive palette (as well as a consciousness of architectural mediation, through film, photography and discourse).

What is postmodernism's legacy and why?

Postmodernism's greatest success was in fracturing expectations about period style -- so we no longer think of ourselves as working to a single shared "look." This is ironic, since postmodernism itself was such an extreme style and did indeed sweep through ever genre of design in the '80s -- fashion, TV and film, graphics, interior decoration, etc. But its techniques of complete fragmentation and its prioritization of difference over unity really transformed ideas of design, such that "post-postmodern" culture is defined not so much by stylistic coherence, but by other issues such as technology (the internet), ethical imperatives (environmentalism), and perhaps production strategies (as in the Chinese economic boom).

"Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990," will be at the V&A Museum from Sept. 24, 2011 to Jan. 15 2012. The exhibition is supported by the Friends of the V&A with further support from Barclays Wealth. For more information, go to http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/postmodernism/.

For more by J. Michael Welton, go to http://architectsandartisans.com

Photo permission granted by Victoria & Albert Museum