Club ownership in England's top flight has abandoned the age of butchers and bookies and embraced the world's garish mega-rich.

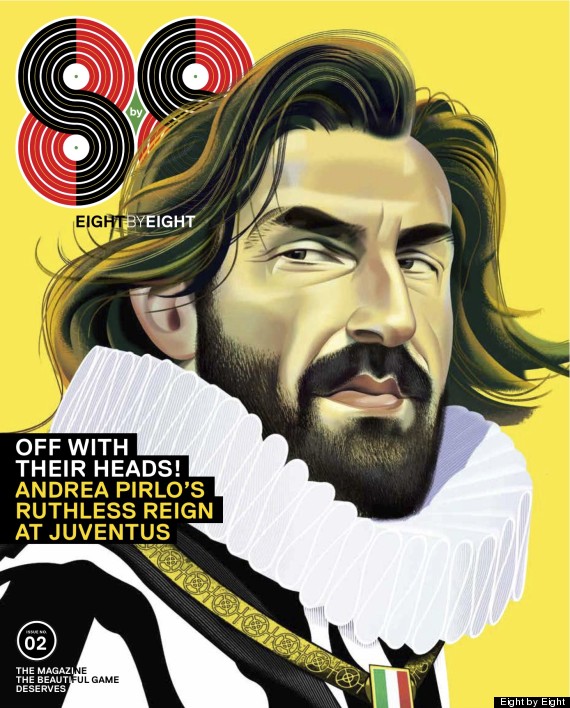

Cross-posted from Eight by Eight magazine

By Stan Hey

When I first started going to football matches as a 10-year-old in the early 1960s, it was very rare to know anything about the owners or chairmen of football clubs, the majority being long-serving aldermen, trusted accountants, and justices of the peace -- pillars of the local community with lots of professional initials after their names.

These owners managed a club's business and disciplines but otherwise kept low profiles, and media interest in them was nonexistent. There was, of course, an occasional exception when owners came into the public eye because of the achievements of their club or their own eccentric behavior.

The 1960, Division 1 champions, Burnley, were bossed by Bob Lord, a forthright local butcher with a chain of shops that provided the pies that served as supporters' staple prematch snack. Lord frequently mouthed off against the Football Association and offensively denounced "the Jews in London" running the game. Sidney Wale of Tottenham Hotspur, who did the League and Cup double in 1961, was equally vociferous. And though the Cobbold family -- owners of the 1962 champions, Ipswich Town -- were the epitome of country gentry, Lady Blanche Cobbold's successor Patrick later became the scourge of sports journalists by answering their phone calls with a brisk "fuck off" on the basis that they couldn't quote him and wouldn't call back.

The Moores family, headed by John, held majority shares in both Everton (1963 champions) and Liverpool (1964 and '66), funded by their famous football-betting-coupon and mail-order company Littlewoods, which was based in the city. Meanwhile, the larger-than-life Louis Edwards, a wholesale butcher, oversaw the Manchester United champion team of 1965 and '67. Pies, beer, meat, betting, and retail sourced the ownership of England's major clubs.

Fifty years on, a brief assessment of current club proprietors reveals oil, minerals, gas, and international finance as their source of wealth, and just as the commodities that fund ownership are now global, the owners are very far from being local. Russian, American, Emirati , Egyptian, and Malaysian billionaires now sit in the cushioned seats where the stolid English burghers once surveyed their empires. Joe Lewis, who rose from East London poverty to become one of the world's biggest currency dealers, owns Tottenham Hotspur but resides in the Bahamas. Eleven of the 20 Premier League clubs in 2014 are technically in foreign hands.

This burst of overseas entrepreneurial interest in the English game could not have been envisaged in the dark decades of 1970-90, when hooliganism and stadium disasters accorded it pariah status. Investors walked away; the idea of floating clubs on the London Stock Exchange backfired too. Even the Edwards family wanted out of Manchester United. I was reporting from Old Trafford when new owner Michael Knighton celebrated the acceptance of his £20 million bid in 1989 and, like the fans, gasped in bewilderment as he ran onto the pitch in team kit, juggling a ball. It turned out that Knighton was more Walter Mitty than Charlie Mitten, a postwar United forward. Rupert Murdoch also bid but was repelled, though as football found out, he had another plan.

Murdoch's purchase of the media rights to the English game, just as the top 20 league clubs broke away from the other 72 to form the Premier League, created a new reservoir of wealth. Clubs wanted more broadcast revenue; Murdoch wanted more viewers. "Sport is my battering ram," he announced, and football headed the charge. The fees that Murdoch paid the Premier League (the most recent deal cost £2.3 billion) enabled the clubs to spend on exotic and expensive players. Significant names included Eric Cantona at United (via Leeds) and Dennis Bergkamp at Arsenal.

The profile of owners changed, too, in the 1990s: local stalwarts became serious entrepreneurs convinced that their investments wouldn't be a sentimental tossing of money down the drain. Steel millionaire Jack Walker put together a Blackburn Rovers team to win the Premiership in 1995, while Tottenham Hotspurs owner Alan Sugar, enriched by his Amstrad computers, invested in German star Jürgen Klinsmann -- though the future United States coach's abrupt departure for Bayern Munich left Sugar snorting, "I wouldn't wash my car with the signed shirt he gave me."

As the profile of the English teams spread through satellite coverage, massive merchandise revenue began to flow from the Asia-Pacific region, and the global branding enticed international owners. When the previously unknown Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich bought Chelsea in 2004, he established the model -- invest big money, pick the best coach for the job, win trophies, make profits, do what you like.

A year later, the Glazer family, owners of the NFL's Tampa Bay Buccaneers, raised the stakes when they bought Manchester United for £790 million (a somewhat higher price than Knighton's £20 million) and introduced English football to the concept of the leveraged buyout. Randy Lerner, then owner of the Cleveland Browns and chairman of bank holding company MBNA, fell in love with football during a year at Clare College, Cambridge, and took Aston Villa off veteran owner "Deadly" Doug Ellis, so called for his penchant for sacking managers. Tom Hicks, the former owner of the MLB's Texas Rangers, and George Gillett, majority shareholder of the NHL's Montreal Canadiens, pitched up to buy Liverpool from the last of the Moores family, while Stan Kroenke, owner of St. Louis Rams, and Ellis Short, president of Lone Star Investment, upped their stakes to control Arsenal and Sunderland, respectively.

But the biggest coup came in 2008, when Sheik Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi fronted the purchase of Manchester City, rescuing the club from the grip of controversial Thai businessman tycoon and former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The Arab prince promptly mounted a 10 million petro-dollar assault on the title, succeeding in 2012. The boardroom portraits of all those familiar long-standing English owners were taken down. Their days were over.

This changed world has several common factors: increased ticket prices for the fans, higher wages for players, and a tighter control on the media. I once walked into Manchester United's old training ground at 7 a.m. and bagged an interview with Alex Ferguson; these days, at most clubs, you are vetted for any previously unhelpful views. Even the managers have learned that job security is an oxymoron. Owners increasingly exercise power on a whim.

Not all fans of steroid-enhanced clubs are happy. United dissenters deplore the Glazers' loading of interest onto the club, and while last year's listing of shares on the New York Stock Exchange, raising $100 million, reduced the debt, it further distanced the club from its city. Most Villa fans worry about Lerner's austerity in the transfer market even after his $1 billion sale of the Browns. And though Arsenal paid £42 million for Mesut Özil, the Gunners faithful would like the riches of Kroenke and co-owner Alisher Usmanov, an Uzbek mining billionaire, to be deployed on a backup striker. Liverpool supporters, still scarred by the Hicks-Gillett fiasco, are warming up to John W. Henry -- he showed strong leadership in insisting that Luis Suárez was not for sale. But he also spent $70 million buying the Boston Globe, and they suspect that the World Series-winning Red Sox are closer to his heart.

Even Chelsea loyalists felt angry when Abramovich, having sacked a Champions League-winning manager, insensitively installed Liverpool's Rafael Benítez as interim manager. Cardiff fans grumbled when their Malaysian owner Vincent Tan changed the team colors from its historical blue to Asia's "lucky" red, before getting another shiver when Tan replaced the club's main administrator with a 23-year-old Kazakh friend of his son's. Emboldened by this victory, Vincent Tan has since behaved more like Vincent Price -- apparently phoning down to the bench to suggest in-game tactics and then dangling former manager Malky Mackay's future in a public e-mail. A fan protest brought a brief stay, but days after Christmas, the black-gloved Tan canned Mackay. Meanwhile, Hull City's Egyptian owner is about to rename the club as the Hull Tigers.

So, now many English fans are regretting this transition. None of the new owners have roots in the community. Most of them don't turn up for games and rarely give interviews. There's a sense of loss among many supporters. In my youth, Liverpool players passed by our house on their way to catch a bus to training and I cleaned manager Bill Shankly's Ford Corsair in a car wash, getting a Cup Final ticket for my trouble. Localism is all but gone. And the big fear is of retrenchment, that if something goes wrong back home -- a commodity-price plunge, a geopolitical shift -- the foreign owners will cash in their English holdings and walk, leaving behind a lot more than stale beer and unsold meat pies.

Issue 02 of Eight by Eight is available now. Download a free preview here.