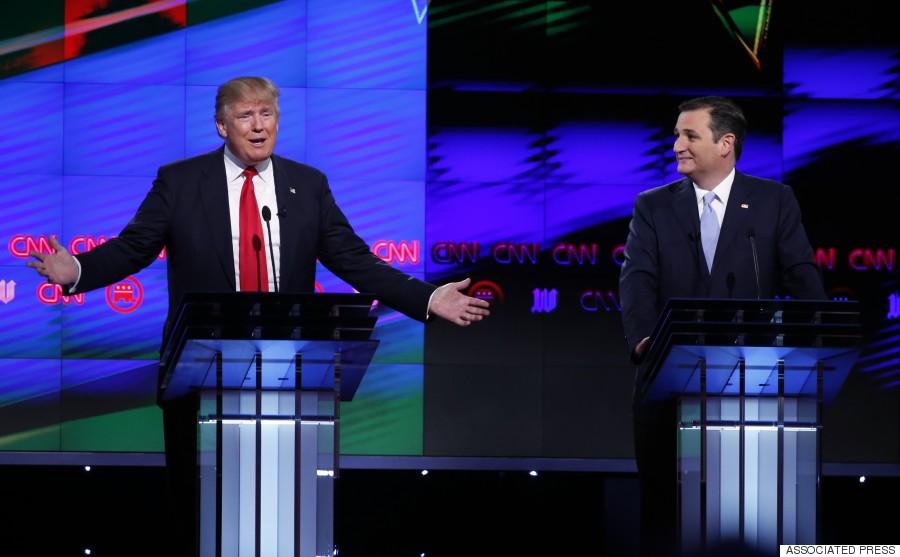

MELBOURNE, Australia -- With the U.S. Republican and Democratic National Conventions a little under three months away, the spectacle of the presidential primaries gathers steam with each passing day. But while commentators are busy asking the big questions -- like whether Bernie Sanders has changed American politics forever or how Donald Trump's run has destroyed the Republican Party -- American voters have expressed doubts in a recent poll about whether the primaries are the right way to establish the quality of party nominees.

Revealed in a March Pew Research Center survey was the stark finding that only 35 percent of voters felt the primaries were a good method for determining the best qualified nominee. While this figure is up five points from the 2012 survey, the Pew data shows that not since 1988 have more than 50 percent of voters felt the primaries were a good way of deciding the most qualified nominee. But the real sting in the survey's tail was the related finding that almost two-thirds, 65 percent, of surveyed voters said they have little or no confidence in the political wisdom of the American public to make the right decisions and choose the person best suited to lead their country.

So central are primaries and public opinion to presidential elections that these sentiments will likely continue to fly under the radar as the July conventions approach. That's a shame. In these numbers, voters are saying something important: the aptitude of their would-be leaders worries them, as do the electoral mechanisms currently used to decide their country's leadership.

Of course, it's possible that these sentiments may be due to what's known as "voter fatigue" syndrome. Maybe because of what we've already seen this election, voters could be voicing their annoyance at yet another drawn-out primary campaign that's likely to cost billions of dollars and leave nothing but significant political rifts in both the Democratic and Republican parties, not to mention a cast of candidates many think would make for "terrible" presidents.

The best political leaders and the most stable political systems aren't necessarily produced through 'one person, one vote.'

But could American voters also be expressing deeper concerns over something that leaders in Singapore and China of all places have long known: the best political leaders and the most stable political systems aren't necessarily produced through "one person, one vote."

This might sound alarmingly anti-democratic. It's not. As Daniel Bell, the Beijing-based Canadian scholar, recently argued, really it's just a different way of thinking about how a political system can ensure its leaders are politically and morally deserving of the power they hold.

You might call this autocracy. For Bell, the better label is meritocracy.

However, if taking pointers from China sounds rather unappealing to the average American, perhaps dipping one's toe into Singapore can provide an understanding of meritocracy without having to deal with the excess baggage that comes with Communism.

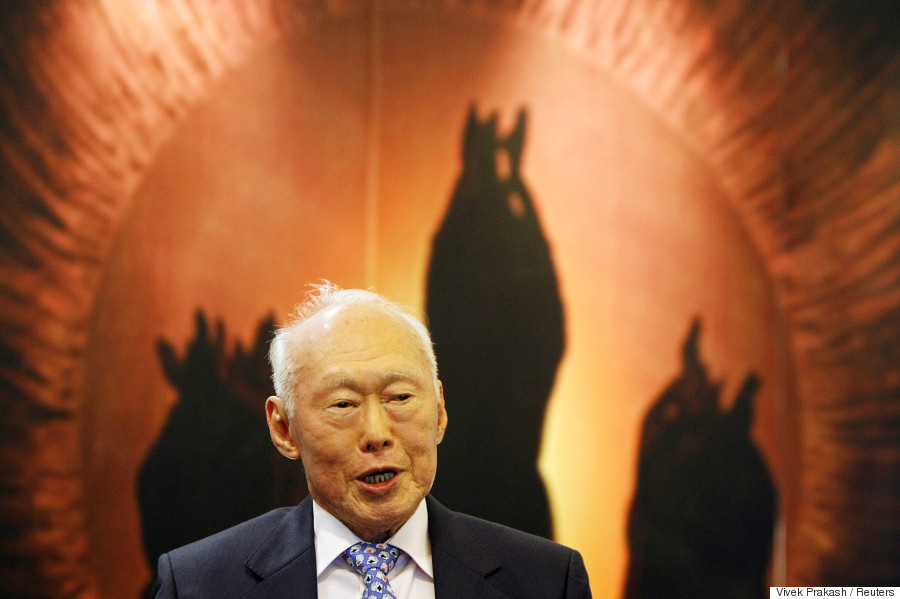

The Case of Singapore

In Singapore, it has been common practice for some time to select top political leaders based on merit, not popularity. As the country's founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, once put it: "Singapore is a society based on effort and merit, not wealth or privilege depending on birth."

Those who lead -- men and women who have "risen through their own merit, hard work and high performance" -- are those whom, in Lee's words, "we must expend our limited and slender resources in order that they will provide the yeast, that ferment, that catalyst in our society which alone will ensure that Singapore shall maintain ... the social organization which enables us, with almost no natural resources, to provide the second highest standard of living in Asia."

Singapore is far from perfect of course. Elections are held, but they are rarely "free." Its media is heavily censored and opposition candidates find themselves targeted by the government and police.

In Singapore, it has been common practice for some time to select top political leaders based on merit, not popularity.

Luckily, the country is improving its record on these fronts. But even as it does so, Singapore remains steadfast to the idea that leaders who are selected and promoted on the basis of their intellectual and emotional intelligence are better equipped to deal with the country's long-term challenges than those selected on the basis of popularity. Drawing on Confucian ideals, this model of government doesn't sacralize popular elections or public opinion over proven political leaders who stake their honor on their track record to do what's right for the people -- now and into the future.

America is clearly not a political meritocracy in the way that Singapore is. It's an electoral democracy grounded in the principles of free, fair, regular, multi-party elections. A popularly elected president who's constantly accountable to the popular will is the best safeguard against political folly and instability. This is the cornerstone of American politics.

Even so, America's current system of electoral democracy isn't beyond reproach. And if voters' sentiments are correct, then a dash more meritocracy may be the way to go.

The good news is that America doesn't need to become anything like a Singapore, or China for that matter, to realize what many voters imply they want -- reforms to the current process of selecting political leaders to ensure political decisions are made only by suitably qualified citizens and political office held only by meritorious candidates.

In the first instance, this could re-open the door to debates about whether restricting presidents to only one, albeit longer, term in office might lead to better government.

It's often noted that presidents who don't have to contend with re-election are typically less corrupted by playing politics and thus more willing to make the tough decisions -- even when those decisions are unpopular. Giving presidents one, longer term in office won't magically guarantee better leaders or governments. But it might diminish some of the political distractions which currently limit what first-term presidents, many of whom desire a second term in office, can achieve. A one-term six-year presidency may provide two years less in office but offer no less time for presidents to actually govern. It'd also mean holding two, not three, presidential elections every 12 years.

Of course, presidents who perceive that they have nothing left to win can sometimes become unaccountable to the people. They can ignore popular sentiment and go their own way. This is one possible scenario. The other equally likely scenario is that presidents not yoked to the dictates of daily opinion polls will have greater leeway to govern and to hopefully deliver what they promised during election time.

While far from perfect, Bell argues that the China model of political meritocracy has shown us over the past several decades that leaders who don't need to constantly remain popular with voters or beholden to special interests -- particularly when doing so undermines the greater good -- may actually be better placed to make the right decisions. Remaining in touch with citizens is one thing; making decisions based on short-term, populist demands simply to remain popular is another. But even in China, citizens continue to judge their politicians based not on what they say, but by what they actually achieve.

Even in China, citizens continue to judge their politicians based not on what they say, but by what they actually achieve.

Another more encompassing proposal for reform not limited to presidential terms would be for America to consider adopting a modified version of what's known as the "horizontal model." Here, both democratic and meritocratic institutions coexist to keep each other in check.

Sun Yat-sen, widely considered the founding father of both modern China and Taiwan, famously made the case for such a model based on a five-power constitution: legislature, executive, judiciary, control yuan and examination. No American would likely find the first three of his branches of government controversial. But what about the latter two?

Sun envisioned the control yuan, or supervisory branch, as an independent government ombudsman empowered to monitor the other branches of government. According to Sun, having such an institution would improve the U.S. constitutional system where "the supervisory power rests with Congress, which has frequently made arbitrary use of it to coerce the executive branch into doing its bidding." It's been noted that something akin to the control yuan already exists in America. The Government Accountability Office operates precisely to audit and investigate the actions of Congress.

Added to this is a fifth branch known as the examination branch. To educate the at times inexperienced and underqualified political leaders that Americans like to elect into top office, Sun recommended an examination system inspired from imperial China where all officials would undergo rigorous training and testing before reaching positions of power. Sun was adamant on this point: "Whether elected or not, officials must pass those examinations before assuming office."

The question is: can America implement such a branch of government? The short answer is no. It's not realistic to hope for reforms that would make politicians undergo training in government and pass an examination before they assume office.

However, just because a formal examination branch is constitutionally unlikely does not mean that the state cannot train its citizens -- some of whom will inevitably become the future leaders of the country -- through better civic education and voter testing to ensure that when they do vote they will have the political knowledge, if not always political wisdom, to choose what's right for the country.

All of a sudden Sun's radical proposal may, with a bit of tinkering, provide the tonic needed to ensure America's political system remains robust enough to handle all that the 21st century will throw its way.

Earlier on WorldPost: