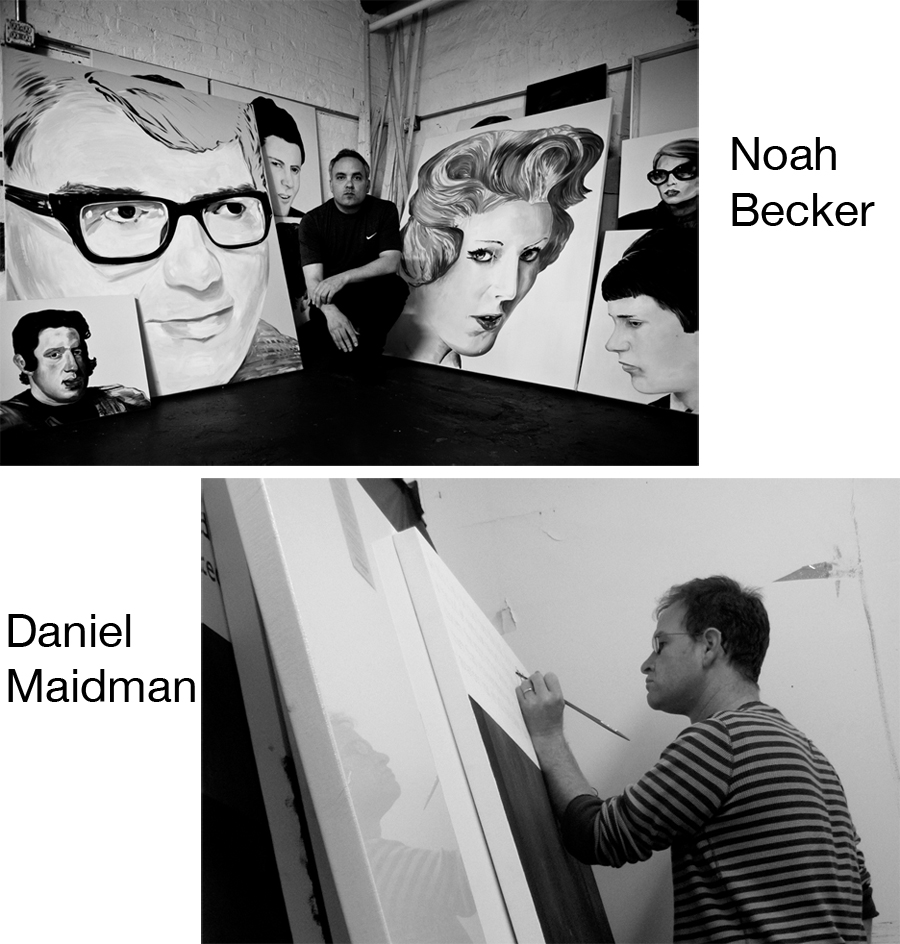

Noah Becker and Daniel Maidman both make figurative paintings and write about art. Their conversation, conducted by email over several days, illustrates two people with profoundly different outlooks on their many points of commonality working towards a shared vocabulary for talking about art.

Daniel Maidman: Tell us a bit about yourself -- you're a widely shown painter, and an extensively published art writer and editor. In which part of the visual art field did you start, and where do your priorities lie now? How do your various pursuits in the field interact with one another and inform one another? Feel free to reject any uninteresting questions, by the way.

Noah Becker: My beginning was a classical one. Things like copying marble statues in Italy and copying Velasquez. At a certain point I really got into Francis Bacon. After a while I realized that painterly technique was not the only focus when making art. Through my interactions with great artists and my times in the New York art world I started to find ways of working on different things. I came back to the technique of painting and an interest in old paintings as a way to produce important contemporary art. A lot of painting is against this interest. I suppose you can make ideas out of any material and painting is as good a medium as any. The conceptual inclination to reject craft and handwork is kind of what I am pointing towards but it runs deeper than that. Certainly writing opens more pathways and leads one to other places. The idea of making work inspired by things outside of painting or the art world is also something that interests me.

DM: You use some constructions here that ring a bell for me -- the idea that the choice to paint needs to be defended and hedged; that painting needs to demonstrate its legitimacy in the face of the contemporary, the conceptual, and the rejection of linkage between the quality of the work and the quality of its execution. I see anxiety on this front as contributing to a lot of hesitant painting on the representational end of the spectrum, especially in figurative painting. It often has a cringing quality to it. I've done my best to set this aside in my own work -- to say of whatever I'm working on, "This is what I'm doing; you can come to it, or not, but I will not apologize or justify." I actually don't get any of that sense of anxiety from your work. It looks decisive. It doesn't look envious of what it isn't. So it's surprising to me that you're absorbed with these issues. Your answer reads to me as an answer describing the forces that oppose your painting. Tell me more about the factors acting in favor of painting -- your drive to paint. This seems to me to be coming through with integrity in your work, and I don't think I understand yet the flavor of your particular drive.

NB: It's a drive that involves the two dimensional illusion of realism. Painting the figure is part of it but painting the figure has already been done. I'm a person who finds new challenges in painting so I pursue it. There are pockets of people who think that high ideals in painting are important. For example in your own work you have a lot of skill and the ability to make figurative elements realistic. There are only a few artists making paintings in this way who are considered important contemporary artists.

DM: I'm always aware of that, and it puts me in a bit of a spot. I think the two camps -- in my personal shorthand, the cool and the uncool -- have distinct and characteristic virtues and flaws. I feel uncomfortable pledging allegiance entirely to either one. I think that at its best the cool scene winds up asking more substantial questions of its work. Fundamental questions are exciting to be around, because even attempting to answer them will necessarily generate new methods of learning and making. At its complementary best, the uncool scene turns to rock-solid virtues -- skill, joy in sight, love of humanity - which are so well established as to be beyond question. I'd like to partake of the virtues of each camp without being consumed by the flaws of either -- the fickle distractability of the cool, the reactionary self-ghettoization of the uncool. It sounds to me like you're at a point in your work where seeking questions is a primary focus. Your work to me has an almost icy calm, a flatness of affect that can reach towards the clinical. But I have the impression that a lot of your portraits are of friends. This produces a conflict: on the one hand, I the viewer imagine you have strong feelings about your subjects. And on the other hand, the evidence of these feelings seems suppressed in the work itself. So one could say that the work is not about the feelings, or the flatness, but about the discord between the two. Am I off-base in seeing such a tension in the work, or is this a theme you're exploring and could verbalize about as well?

NB: The paintings are from photos of hair models from the 1960s and '70s in the U.K.

DM: Yowza! I'm not sure how I formed such a completely incorrect impression. Let's rewind. What's the deal with these portraits? I'm still seeing the drained color, the flat affect -- but I want to see more, or more deeply -- I want to see them as you see them. What I mean is, for instance, when I'm working up a series, there will be some originating idea, and that idea will be a unique inspiration, but it will also tend to be fairly monopolar in the aspect of the work it addresses -- the conceptual, the formal, or the emotional. I can't really start until I've fleshed out the project to answer questions raised by each of these poles of art-making. So for any series I worked on, I could ordinarily speak about it in terms of a dissection of all those elements. I'm not claiming here that your process should in any way resemble this, but would it be possible to pull apart what you're up to at some comparable degree of resolution, so that I can think about it in fine detail alongside you?

NB: I'm going for a mood, the portraits unlike the paintings on my site that feature more figures are not telling a narrative. The pictures with more figures are kind of not narrative either. The mood is my idea and the rest of it is not within my control. You can't plan on the unknown. If it's all figured out it's illustration and I am not an illustrator.

DM: Before we go on, let me respond to your insinuation that my approach makes me an illustrator. Somewhere in "An Actor Prepares," Stanislavsky explains that the actor spends years acquiring and refining skills, so that when he finally steps onstage, those skills will come organically to the aid of his inspiration, enriching and amplifying its expression. This is the theoretical principle which most high-rendering representationalists embrace. I certainly do. That said, I should reiterate that I have absolutely nothing against the way you've chosen to make work, either in terms of your practical techniques or your developmental procedure. I think there's lots of room in the wide aesthetic universe for differences in approach, and I think that what you're doing works. So far I feel like I've been raising topics you're not especially interested in discussing. I'm pretty flexible in terms of things I find interesting to discuss - why don't you raise some issues that you've been hashing over lately, and we can talk about those?

NB: I was not specifically commenting on your work, I enjoy what you do. My intention was to question painters who congregate and worship technique. Who is your favorite artist and what have you gained from certain artists?

DM: Aha -- many apologies, for that and for general Jiminy Glickishness so far. I'm not part of the camp you're describing, and I don't necessarily subscribe to their program, but I've got a lot of good to say about them, if you're interested in getting more into that. I don't have a single favorite artist, but we've got a point of overlap -- Velazquez is a huge big deal for me, for a few reasons. The humanity he sees in his subjects is overwhelming, and especially his interest in the psychology of dignity. I think he seeks out people who are in a position to be humiliated not because he's interested in humiliation per se, but because he's interested in dignity; without an opposing force, dignity does not assert itself. He is always looking for people who would be beaten down if the will to stand failed them. This is magnificent. On a technical level, he is one of the first painters to learn to cooperate with what the eye does not see. He doesn't paint everything, only everything you see at certain rates of looking. The missing information tells you how to look at the work, and the work never seems incomplete or unconvincing. That's a profound understanding of vision. And also there's Las Meninas. What is Velazquez to you?

NB: I don't have an opinion of Velasquez, I have a point of view which is fully formed based on many years of study. Velasquez is an example of painting triumphing over photography. There has never been a photograph that is more real than a Velasquez. Velasquez is also an influence on Manet who I love and Sargent who I love much less and of course the great Francis Bacon. John Currin made a good point which is that no matter how influenced we are by great European painting we will always be Americans and never be European painters.

DM: How does Americanness inform your work? How does Canadianness enter the equation?

NB: It's my dual citizenship that makes this one big country. I think being raised by American parents makes me more American but I grew up surrounded by Canadians so it's hard to tell. The nationality of any person influences them to a certain extent. When I see European art I want to be European.

DM: I actually know exactly what you mean. My parents are from Philadelphia, I was born in Toronto, and I'm dual. I don't notice my particularly United-Statesian assumptions until I'm in Canada or Europe, and I can observe other default outlooks. I have wanted to be a Russian novelist, a Greek tragedian, an Italian painter, a Scottish industrialist... let's say you're standing in front of Juan de Pareja or something. You want to be a European painter, and then -- what? What is the chain of thought and feeling between that impulse, and your recognition that it is not going to happen?

NB: I'm not as interested in my organic impulses when I look at paintings. I did all that when I was 14, now I'm more concerned with my idea. The problem with painters is that they have too much fun with painting. Painting is just a way to make things or put ideas forward, that's it. Nothing mystical, nothing sacred, nothing complicated.

[I'm not being dismissive I really feel that way at this point in my career.]

DM: [Thanks for the reassurance, and it's totally cool. Your prescriptive phrasing threw me before, but now I'm applying a "this is how Noah sees things relative to himself as an artist" filter, and not taking anything personally.]

NB: [yes please! :) ]

DM: You're describing painting here as a vehicle for putting forward your idea. Earlier, you had described your work in terms of a mood, which was your idea. Are you using "mood" and "idea" interchangeably, or is there a transformation from the originating inspiration before you are ready to paint?

NB: It's all part of a process, all I'm saying is that the idea plays a larger role in my work and mood plays into that. It's non-literal. What are some of your favorite contemporary artists who do not make paintings?

DM: I'm a sucker for Serra. I like Kiki Smith's sense of materials relative to her themes. I think Jesse Soodalter's eye for composition is incredible. I love Erika Johnson's microbe photography. I was thinking about Sol LeWitt in response to your question, and then I realized that where I wanted to go with that was Richard Feynman and his Feynman diagrams, and Rosalind Franklin's X-ray crystallography of DNA, and bubble chamber photography, and the atomic imaging they're doing at the IBM labs. In general, if you're moving out of the range of classical representation, I think empirical science is a profoundly beautiful theme and organizing aesthetic for visual work.

NB: This is good to know about you Daniel, thanks for taking the time to have this conversation, the first of many I hope.

DM: Likewise, Noah, it's been a pleasure getting to know a bit about how you see and make art. I'll look forward to doing it again.

Noah Becker, Supper, 2013, 48" x 60", oil on canvas

Daniel Maidman, The Peacock (detail), 2013, 48"x24", oil on canvas

---

Noah Becker is an acclaimed oil painter, a jazz saxophonist, and the founding editor of Whitehot Magazine. He is also a contributing writer for Art in America, Interview Magazine, Canadian Art, The Huffington Post, ARTVOICES and New York Arts Magazine. His work was recently exhibited in Detroit with David Shrigley and Michael Borremans in a show curated by Dick Goody. He's showing in two future shows organized by curator Kristin Sancken. His work will debut in London in July at Flowers Gallery in a group show of self portraits. He is showing with artist/curator Aubrey Romer at Art Hamptons. He will have a solo show at the Lodge Gallery on Christie street in New York this November. Becker lives and works in New York City.

Daniel Maidman is a Brooklyn painter whose art has been shown in group and solo shows in Manhattan, was selected by the Saatchi Gallery to be displayed at Gallery Mess in London, and has been exhibited at the Alden B. Dow Museum of Science and Art. His art and writing on art have been featured in ARTnews, The Huffington Post, International Artist, Poets/Artists, MAKE (forthcoming issue), Manifest, and Catapult. His work is included in numerous private collections, among them those of New York Magazine senior art critic Jerry Saltz, Chicago collector Howard Tullman, best-selling novelist China Miéville, Disney senior vice president Jackson George, author Kathleen Rooney, and Gemini-winning screenwriter Jeremy Boxen.