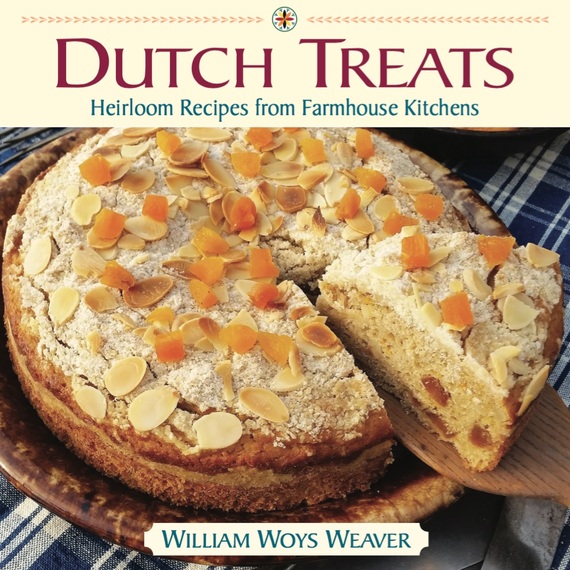

Dr. William Woys Weaver is an internationally known food historian, gardener and cookbook author. He has written sixteen cookbooks, many focus on Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania Dutch foods. In his latest book, Dutch Treats: Heirloom Recipes from Farmhouse Kitchens, Dr. Weaver presents more than just recipes, but also a rich history on the Pennsylvania Dutch, their culture and their way of life.

When did your fascination with the Pennsylvania Dutch culture begin?

Since my parents were working to save money for a house, I was more or less raised by my grandmother and grandfather Weaver, at least in my most formative years. I learned about Pennsylvania Dutch culture from my grandfather who was born in Lancaster County and also spoke Pennsylfaanisch, or Deitsch as some people call it. So he told me folk tales and spoke to me in Pennsylfaanisch all the time. To my child's mind, the Dutch Country became this magical place over the Welsh Mountains (to the west of Chester County where I grew up) where beautiful gardens grew in abundance and people made the most wonderful things in their kitchens. And since my grandmother learned to cook Dutch and made excellent shoofly pies, sauerkraut and other traditional fare, I was exposed to the culture very early on. Dutch culture is very much table oriented, so the learning curve took place during meals.

Later, even though I eventually grew up "outside" the culture, mostly in New York, the Pennsylvania Dutch Country always held a special draw. This is where I felt at home. These were my roots, yet due to my outsider upbringing, I was also able to study and understand it in a balanced and unbiased way. I think this interest was also fortified by the fact that my grandfather had done the family genealogy and was proud of our Swiss heritage. He talked about it all the time and he drove me to Lancaster one time to show me the 1730s house built by our ancestor Hans Weber. All his cousins out there spoke Dutch; it was like visiting a foreign country and yet feeling right a home. We were Weavers, part of an old extended clan.

Pennsylvania Dutch and Amish are often used interchangeably. Is that accurate?

Pennsylvania Dutch and Amish are often used interchangeably but this is inaccurate. I took up the origins of that idea in my book As American As Shoofly Pie which explains that the culture is composed of a melding of "Drittels" (thirds). About 1/3 of the Pennsylvania Dutch hail from the Palatinate and Alsace, another third from Wuerttemberg, primarily Swabia; and the last third consists of the Swiss element, which includes the Plain Sects like the Mennonites and Amish. The dialects from those regions eventually evolved into the distinct American language we call Pennsylvania Dutch. Numerically the Amish make up about 5 to 10 percent of the total Pennsylvania Dutch population which is mostly Lutherans and other mainstream church groups.

When did the lines begin to blur?

During the 1930s and 1940s travel journalists, especially Ann Hark who wrote a number of books about the Dutch, began to equate Pennsylvania Dutch with Amish both for socio-economic and political reasons. Pennsylvania Dutch became a metaphor for noble peasants, and the Amish fit that bill since their pacifism played into the Isolationist politics of the time. In truth, Amish culture is mostly derivative of the world around it, so much of what the outside world considers Amish (like whoopee pies) actually comes from somewhere else. Even Old Order Amish bonnets were copied from the Quakers. The most creative culinary element of Pennsylvania Dutch culture were the Swabians: they owned the hotels, the restaurants, the beer breweries (like Yuenglings today), and they were the pretzel bakers of colonial Pennsylvania.

In your latest book, Dutch Treats: Heirloom Recipes from Farmhouse Kitchens, you say "Pennsylvanian Dutch cookery - the real thing, not the pallid tourist knock-off - remains a buried treasure in America's own backyard ... " What is the difference between the two?

Pennsylvania Dutch cooking has suffered a bad reputation from the tourist cuisine that has sprung up in areas catering to Amish tourism. The evolution of this type of food is traced in As American As Shoofly Pie. It started in the 1930s under the guise of the "Amish Table" a menu supposedly reflecting what Amish people ate at home. Unfortunately, good Pennsylvania Dutch home cooking is not always easy to translate into restaurant fare, and so the tourist industry came up with certain inexpensive iconic dishes that would verify the authenticity of their meals. This includes (even today) the seven sweets and seven sours (an array of pickles and preserves) which was created in the 1920s at the Valley House Hotel in Skippack, PA; Schnitz-un-Gnepp (a stew of dried apples and ham) - a dish that was never eaten on special occasions and generally made from leftovers; chicken pot pie (which was not invented by the Dutch, it was just common farmhouse fare in the 1800s), and of course shoofly pie. But even most of these items popular in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s have fallen off many menus only to be replaced with hamburgers, pizzas, whatever may appeal to tourists on low budgets.

What makes food - in particular Pennsylvania Dutch food - authentic?

What makes food authentic as opposed to a highly filtered and packaged experience depends a great deal on what one considers authentic. Authentic is really derived from personal mythologies, personal ideas about reality. Thus it is that in As American As Shoofly Pie there are dishes some Dutch do not consider authentic because they did not grow up with them. When you undertake field work and interviews as I have you discover that Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine consists of many authenticities, it is the sum total of all of them, not the narrow perspective of someone who never ate a New Years Pretzel, or a Sugar Kringle, or Jolly Molly's Saffron Pie. Many families never ate out, so they would not know much about restaurant specialties, and if you don't undertake field work you are not likely to discover that right down the road there may be a dish you never heard of but is quite popular in that particular community (Rough-and-Ready Cake for example).

Pennsylvania Dutch fare goes deeper than the food itself. Can you tell us a bit about the folklore behind many of the dishes?

Pennsylvania Dutch foodways are rich in folklore and tradition. I tried very hard in Dutch Treats to include recipes that reflected those stories and old-time beliefs. Each dish has its own unique story, like Antler Cookies set out in the woods for the Waldmops (a woodland elf), scattering crumbs of a special bread in the four corners of the kitchen garden to insure that the Gleene Leit (wee folk) would take good care of it and insure a respectable crop. Then there is the mythical Elbedritsch a bird-like creature that lives in the woods and makes its nest in peppernut trees (trees that bear peppernut cookies as "fruit"). There are New Years Pretzels which you break on New Years for good luck, Bean Day Bread which is made on June 4th to celebrate the planting of the summer bean crop. The list is very long and fascinating. I am tempted to write a book about Pennsylvania folk tales. I don't think anyone has done that.

How is this culture of cooking relevant in today's culinary world?

Pennsylvania Dutch cookery is becoming a trend at the moment because it is land based, that is derived from the countryside and thus perfect for the farm-to-table movement. Many chefs come to me to garner ideas for their restaurant menus, and it is a great pleasure of mine to see them take traditional dishes and reinvent them in new ways.

Have you heard of any of your recipes making their way on to restaurant menus?

Yes, many recipes in Dutch Treats are now on menus in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Amish cooking, as promoted by the Lancaster Tourism Bureau, is something defined (and restrained) entirely by religion; real Pennsylvania Dutch cookery is borderless, non-denominational, free of religious boundaries. It is based on fresh ingredients and core dishes inspired by the Old World but reinvented as something uniquely American - shoofly pie is an example of this. Pennsylvania Dutch cooking is a New World cuisine so naturally it should take its place in the national food repertoire.

Tell us about your heirlook seed collection and its relationship to your work?

The Roughwood Seed Collection was begun about 1932 by my grandfather H. Ralph Weaver, the same grandfather who introduced me to Pennsylvania Dutch culture. The story about how he collected seeds and built up a unique seed archive is retold in my book Heirloom Vegetable Gardening. After his death I took the collection, moved it to Devon, Pennsylvania and added to it so that it now comprises some 4500 heirloom varieties. At 84, it is also the oldest private seed collection in Pennsylvania, perhaps the East. I have used the collection as my laboratory to learn more about how these heirloom plants taste and most importantly, how to make them relevant to today's lifestyle. Every book I have written to date has been influenced by the seed collection since I have had easy access to rare and unusual ingredients, even the rare Native American corns and Old World grains that provided me with flour and meal for recipes in Dutch Treats. The collection now operates as a 501c3 non-profit and it is my hope that we can raise enough money to insure its place in the future. The collection needs more space and of course more paid hands to run it. Seed saving is almost a lost art and we have managed to stay true to the old traditional methods for preserving seed: experience that we hope to pass on to other people so that they can grow their own food successfully. The website is www.RoughwoodSeeds.org

Recipe from Dutch Treats (reprinted with permission)

Bigler Cake (Bigler Kuche)

Yield: Serves 8 to 10

Image: William Woys Weaver

3 cups (375g) cake flour

1 cup (250g) sugar

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

Grated zest of 2 lemons

6 tablespoons (90g) unsalted butter

2 eggs

1½ cups (375ml) buttermilk

Coarse sugar or lemon crumbs as topping

Grease the pie pans or cake mold and set aside. Preheat the oven to 375F (190C). Sift together the flour, sugar, baking powder and salt, then add the lemon zest. Make a valley in the center of the dry ingredients. Melt the butter and pour it into the valley. Beat the eggs until lemon colored and frothy, then combine with the buttermilk. Add this to the melted butter and stir the ingredients to form stiff, sticky batter. Pour this into the prepared pie pans or a cake mold that has been greased and dusted with bread or cake crumbs. If using pie pans, sprinkle crumbs over the tops; if using a mold, ice the cake once it is cool. Bake in the preheated oven for 30 to 35 minutes or until fully puffed and set in the middle. If baking in a Bundt mold, bake for 35-40 minutes. Serve at room temperature.