Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

For Quebec, the month of October 1970 was its darkest hour, as the Front de Liberation du Québec (FLQ), a separatist paramilitary group formed in 1963 advocating the creation of an independent Marxist state of Quebec, targeted the government, English speakers and business, and the Catholic Church, which were viewed to be suppressing French-Canadian interests.

Bombings of mailboxes by the FLQ were common throughout Quebec from 1963 to 1970, but other targets included the Montreal Stock Exchange, Montreal City Hall, police offices, railways, and banks.

On October 5, 1970, two members of the FLQ's "Liberation Cell" kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross outside his home. The FLQ demanded the release of detained FLQ members and the public broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto which criticized business, religion and the political leaders of Quebec and Canada. Then on October 10, Pierre Laporte, the Quebec Minister of Labour, was abducted by the "Chenier Cell" while playing football with his family in Saint-Lambert. Thus began the October Crisis.

Commercial areas were closed off and the army was brought in to patrol Montreal and government buildings. With increased difficulty in maintaining civil order, the Quebec Government asked the Canadian army to formally intervene. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, the only time it was used in peacetime in Canadian history, which allowed the government to suspend civil liberties; which led to the arrests of 250 suspected FLQ members and sympathizers within a 12-hour period.

The situation took a turn for the worse when on October 17, the "Chenier Cell" announced that it had murdered Pierre Laporte. On November 6, police raided the hideout of the "Chenier Cell." The government also negotiated with the "Liberation Cell," reaching an agreement on December 3, which saw Cross's release after 62 days in captivity in exchange for safe passage to Cuba for the Cell members.

Only eight individuals were convicted of crimes associated with the October Crisis. Federal troops in Quebec were withdrawn on December 24.

This account was compiled from an interview done for ADST with Vladimir I. Toumanoff (political counselor, Embassy Ottawa). Read the entire account on ADST.org

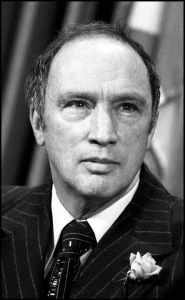

TOUMANOFF: One thinks of Canada as a stable, somewhat staid society. Such, emphatically, was not the case during my tour. Three elements coincided to produce turmoil. One was Pierre Elliot Trudeau (at left), the "JFK of Canada," newly elected Prime Minister, young, energetic, glamorous, brilliant, charismatic, eloquent in both national languages, but with an attitude toward the United States of an arrogant French intellectual aristocrat -- in a word, scornful dislike. Be it said we were not all that likable -- in the midst of the Vietnam War, with Nixon as President, and almost absentmindedly an overwhelming cultural, economic, political and demographic threat to the sanctity of Canada.

Another was an alienated French Québec so resentful of real and imagined oppression and injury at the hands of English-speaking Canada as to be on the verge of secession... And finally, a burgeoning Canadian nationalism, anti-American and anti-Québec in the English provinces, and assertively anti-Anglo and pro-independence in Québec.

The alienation of the French Québecois was so intense it had already spawned the terrorist FLQ the Front de Liberation du Québec, loosely but accurately translated as the Québec Freedom Fighters, which had started blowing up mailboxes with sticks of dynamite by the time I came to the Embassy. The pro-independence political party, which disowned the FLQ, was the Parti Québecois. It had a near majority vote in the Province and had provoked a constitutional crisis.

Trudeau's imperative task was to combat Québec separatism and preserve the unity of Canada. To that end he pursued a three-fold program: to stimulate Canadian patriotism/nationalism; to portray the United States as an ugly, aggressive giant constantly threatening to overwhelm Canada; and to assuage and accommodate Québec as a treasured and protected unique component of Canada.

His calculation was:

1)To generate in English Canada a combination of Canadian nationalism and fear of U.S. takeover in the event of Québec secession. An independent Québec would have broken English Canada into two small, very different clusters of provinces separated by a French nation; each much less able to withstand absorption by the U.S., perhaps piecemeal, province by province. Thus Trudeau would move English Canada to be more sensitive and accommodating to Québec, and the Québecois to forgo secession in order to preserve their own precious Canadian identity and escape the ugly American;

2)To persuade French Québec that independence would leave them isolated and surrounded by a resentful and vengeful English Canada and a giant America, a tiny French island of barely 4 million in a gigantic sea of 250 million Anglos. Better to stay in a caring and accommodating Canada.

By the time I arrived to take up my duties at the Embassy in Ottawa, which was about September of 1969, the FLQ was planting bombs, fused dynamite sticks as I recall, in public mailboxes in Québec and blowing them up.

Then came the worst. A Volkswagen in Montreal ran a red light, was flagged down by the police, the driver jumped out and ran, escaping. In the car the police found a stack of FLQ posters proclaiming that they had kidnapped the American Consul General in Montreal and were holding him hostage. Their demands were something along the lines of immunity from arrest, publication and broadcast of their manifesto, and I think resignation of the Provincial government and a plebiscite on Québec independence. They were a bit premature as they had not yet kidnapped the Consul General, and counter-measures were immediately taken.

The Embassy and all our 12 Consulates across Canada were notified, heavy police guards provided, and the news of the FLQ plot widely publicized. The FLQ, realizing they had lost their chance at an American, moved quickly and promptly seized a British equivalent, I think the British Trade Commissioner in Montreal. Their demands were rejected and an intense hunt began.

However, not long after, the FLQ managed to capture a prominent member of the Québec Government [Pierre Laporte], a Provincial Minister. They held him in a Montreal house, tortured, and ultimately killed him. Some weeks later, they were caught in an outlying farmhouse. The Brit was rescued unharmed. They were tried and jailed, probably for life. They and the FLQ dropped out of public sight. They had also greatly harmed their cause.

Q: And discredited it totally.

TOUMANOFF: Yes, it was too savage for the Canadian culture...Too savage, even for Québécois secessionists. I think there were very few, just a handful of these radical madmen prepared to act that way...

After that FLQ kidnapping poster the Department had to try to address the whole question of terrorism in Canada directed against the Embassy and Americans at large... Individually, we all knew we were targeted. Measures, now familiar, but then quite novel, were instituted. Guards were posted at the buildings and the residences of the Ambassador and Consuls General. For fear of a letter bomb, we were told not to open our mail at home unless we either recognized the handwriting or we were otherwise absolutely confident that it was a legitimate piece of mail. If not, we were told not to open it, to touch it as little as possible, and to call the police, and we were given an emergency 24-hour telephone number which all family members had to carry with them at all times.

We were very careful with the mail, and reasonably so within practical limits in our movements. But we decided not to tell our children unless orders came to evacuate unessential spouses and children. Such orders never did, and no attempt against us or consular personnel took place that I ever heard of. But the Embassy received a couple of bomb scares in the next few months. We would all scramble out and stand around while the police searched the place. They never found anything and nothing ever exploded. But it did take a long time and disrupt things some. It also reminded us not to get sloppy.

The central issue for the separatists was an historic and very present threat to the survival of their French language and culture, from English Canada by both intention and disregard, and from the U.S. by its colossal influence in every sphere. They consequently turned, eagerly, to France as their mother country, for practical support and emotional sustenance. The French response was modest, lukewarm, nothing like the passionate embrace they sought. The French were friendly and recognized historic ties, but seemed somehow preoccupied with other matters, which, of course, they were.

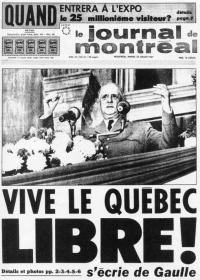

Québec sought a visit by [Charles] de Gaulle, the President of France. After some delay, Trudeau evidently decided it was better to invite de Gaulle on a state visit than to delay indefinitely and inflame the issue to a separatist battle cry. [In 1967] de Gaulle accepted, landed in Montreal to a wild, hero's welcome, and stayed, instead of going on promptly to Ottawa, the capital, as protocol would require. Worse, his public statements increasingly celebrated the ties between Québec and France, until in a public address from the Mayor of Montreal's balcony to the cheering crowd below he ended a real stem-winder with the cry "Vive La Québec Libre!" -- Long Live Free Québec -- the separatist and FLQ rallying cry.

The Trudeau Government promptly invited him to leave Canada, which he did. I read that several ways. In the first place it was a shocking provocation to all the rest of Canada. Secondly, de Gaulle must have known the economic damage separatism was already causing Québec as capital fled and investment faltered. He also must have known that his act would accelerate that damage. Moreover, he had no intention or even capability to provide compensatory support. It was a wanton act of destruction and as such a profound insult to Canada as a measure of how little importance he ascribed to that nation. The episode was also symptomatic of the illusion, more accurately the delusion prevalent in French Québec that France would somehow be the savior of their culture and shield them from their anxieties.