For the past couple years, Rosalie Harris has walked every day to save her left leg At 3 p.m. she laces up her size-eight shoes and treks across Rochdale Village in Jamaica, Queens. Every step she takes is meant to strengthen a body weakened by surgery.

Now, she hobbles with an added purpose: To save the lives of strangers. Harris leans on her metallic cane as she hands out fliers at churches and apartment buildings. She tells others about her own cancer, caught so late that she had to undergo chemotherapy and a mastectomy. The message is zealous: "Get screened early!"

Queens has the highest rate of late-stage breast cancer detection in the nation. It stands at 33 percent versus the national average of 12 percent, according to the Queens Cancer Center. Now a grassroots effort called HealthLink is mobilizing survivors like Harris to reach out in laundry rooms and libraries across the borough to screen women in time.

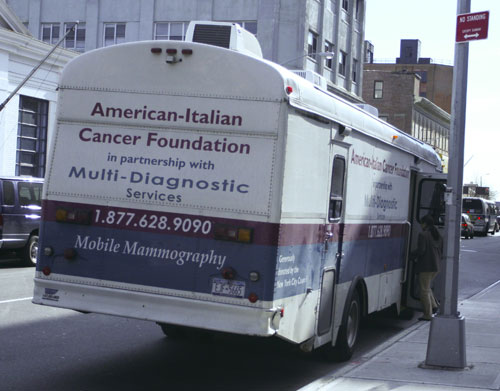

"It's all in where you live. That determines what services are provided to you," Harris said, outside, where the day before a mobile van where medical staff perform up to 40 mammograms a day. "If you don't know what's available to you, you'll never take advantage of it. But we're going to change that."

As well as screening in mobile buses and vans, that are parked in well-traveled corners, the group does outreach in the 12 of the borough's 62 libraries, working in seven languages.

A woman takes advantage of the free mammogram screenings outside the Queens Library in Jamaica.

HealthLink says it has helped some 2,597 women since last year, but many barriers remain, such as routine poverty and lack of primary care. Medical facilities such as St. John's and Mary Immaculate Hospitals have closed, leaving a big gap for treatment. Then there's a general lack of information about screening options and slashed state budgets. This past April, for example, the New York state government shrank the Cancer Services Program's budget to $21 million from $29 million the year before. This program helps provide uninsured women access to screenings and treatments.

On top of all these factors, health care challenges affect Queens' large immigrant population. Nearly half of the borough's roughly 2.2 million residents are foreign-born, from over 100 different countries. This means that language, a distrust of Western medicine and the fear of deportation can discourage immigrants from seeking help.

But HealthLink seeks to reassure such women that they're safe. "You'll never be asked about your immigration status at these screenings or events," said Tamara Michel, 26, HealthLink's Community Outreach Coordinator.

To reach out to various ethnic groups, HealthLink goes through the Queens Public Library, which boasts the highest readership in the country, according to the American Library Association. Each branch has unique programs in the local language of the community that it serves.

"Nothing [no other program] has used the same kind of community organizing approach to put cancer screening right into the library," said Bruce Rapkin, HealthLink's senior scientist.

Through the library, HealthLink works with survivors, such as Harris, whose cancer was caught eight years ago, or caretakers of current victims in each neighborhood who can do outreach about screening options. A dozen councils are currently in operation, with two more set to open in Elmhurst and LeFrak City in January. HealthLink claims to have held 95 events organized by the councils.

"It's so much more meaningful to hear the information from within their community than to hear it from someone coming from outside," said Michel, the outreach coordinator.

The councils use HealthLink for access to tools like the mobile mammography screening vans, which they may have trouble locating on their own.

Harris, who works with the Baisley Park council, for example has organized two screening events since June. The first, in June, transported 23 Jamaica women for free to Queens Hospital. The second was in October and saw 31 women examined on a mobile mammography bus provided by the American Italian Cancer Foundation. The creamy white Thomas Built Bus, which resembles a converted recreational vehicle, is staffed by two technicians and a nurse. It can handle up to 40 screenings in an eight-hour shift.

This grassroots effort saved Robin Scott when, at 40, she discovered a lump in her right breast.

"I wasn't going to get tested at first because I thought the lump was related to my menstrual cycle," said Scott. But her sister, who had seen one of Harris' information sheets in a Rochdale apartment building, urged her to take advantage of the free exam. She was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer, bordering on Stage III.

Fifteen months later, she now has three months left of chemotherapy, which she hopes will prevent the mastectomy the doctors first recommended.

"I am just so glad we found each other, before, before we lost you," said a tearful Harris, sitting across from Scott at the library.

"You were there for me and we'll now be there for other women," replied Scott as she squeezed the other woman's hand.

According to Rapkin, HealthLink's senior scientist, the statistical evidence on the effectiveness of the program is too early to measure. However Dr. Regina Santella, a professor of environmental health services at Columbia's Mailman School of Public Health, enthuses.

"It is definitely beneficial to have an earlier stage of diagnosis and these programs can have a positive impact on making women more aware of the importance of getting mammograms, especially older women," said Santella. "When done properly it can make a difference in increasing screening rates."

HealthLink is entering the penultimate year of a $2 million grant from the National Cancer Institute, a federally funded research and development center. Rapkin hopes to get more grants and ultimately expand the program throughout other libraries in the country.

For now, getting the word out about early screenings is key, Rapkin said.

Rapkin expressed particular concern about recent recommendations by the federal government task force to delay the minimum screening age from 40 to 50. Rapkin predicted that such guidelines would mean more late-stage detections, the very opposite of HealthLink's goal.

"This is one more obstacle we're going to have to overcome," he said.