This is the second installment in the Quest for the Lord of the Nile series. Read Part I here.

Photo by Laura Hubber

From Alexandria I wind up the estuarine Nile to Cairo, where the river turns like some grave thought threading a dream. Here the Nile grinds and clanks with an incessant base note at the frame of the delta, polluted, noisy, demanding...if a crocodile wanted to live in the noxious waters here today, it couldn't. Past sand-colored mosques and beneath the mullioned windows I comb the streets looking for any evidence of a crocodile, but come up with nothing, save a popular extract of crocodile, a philter ointment whose label says, "For you and your happiness." Finally, I step down an alley into the heart of the Khan al-Khalili bazaar, a frantic mélange of old smells and snaking Arabic sounds.

I encounter a man in a beaded robe who tells me I can find a crocodile at El Fishawi Café, and offers to guide me there. I imagine a crocodile, traded like a slave from the south, in some tub in the back, and if so, I know I will want to negotiate to set it free. But as I step into the hazy, hookah-filled café and ask where I might find this wayward animal, a waiter nods to a candy-striped arched doorway. As I lift eyes above the archway I spy a five foot crocodile stuffed and nailed as though in a Victorian trophy room. He is the closest thing to an intact crocodile I will find in Cairo.

Deeper in the bazaar, among the pricelessly bad tourist baubles, I ask the merchants if they have any crocodiles to sell. Ever since Herodotus Egyptians have welcomed foreigners with an admixture of banter, hearty browbeating, effusiveness, and the sort of insincere familiarity associated with people trying to become intimate enough to pick a pocket. So when one man offers to take me up the narrow stairs to his shop I proceed with caution. There he sits me down and offers me tea. In the furbelows and folderol of the chat between the first cup and the second he shows me several interpretations of crocodiles in soapstone and wood, but nothing real. Then into the second cup he asks me to wait and disappears down the stairs...a few minutes later he emerges with the gnarled rolled skin of a 7-foot crocodile. His price is $2000, and I pass, and decline to bargain. He won't tell me where he got it, or any details. It was likely poached, and just by negotiating it could encourage the illegal trade. So, I instead bid on a beautiful hand-made Egyptian cotton abaya. I manage to get him down to half his initial price, and feel pretty good with the deal until the next day when I eye the same robe in the hotel window for half again the price.

Before arriving in Egypt there was a flurry of email exchanges with Eva Dadrian, a Cairo-based reporter for the BBC. I had asked if she could source any experts on crocodiles, and she found but one: Dr. Sherif Baha El Din, an Environmental Consultant and herpetologist who has been surveying the scaly wildlife of Lake Nasser.

In his cluttered Cairo apartment, ornamented equally with toddler toys and renditions of reptiles, I ask Dr. El Din what happened to the crocodiles of the Nile.

"A combination of things. Certainly human population pressure over the centuries...increasing numbers of people competing with wildlife for the river, and winning." Dr. El Din continues to elaborate, citing the first Aswan Dam, finished in 1902, as a primary culprit. It effectively blocked the annual floods, which washed down new populations of crocodiles each year. Now crocodiles are locked upstream.

But it is the lust for crocodile leather that really wiped out the crocodiles in the 20th century, a madness for handbags, shoes, belts and other pelt accessories. By the 1950s professional hunters from all over the world were coming to Egypt to bag crocodiles, not only for their valuable skins, but for their meat, a delicacy to some gourmands, and their fat, used as a curative for rheumatic diseases. By the early 80s the crocodiles of the Egyptian Nile were all gone. That coincided with my 1983 Sobek anniversary trip.

"When did they start to return?"

"In the middle 80s Egypt passed a ban on hunting crocodiles, in the wake of CITES (the Convention of Trade of Endangered Species) putting Nile crocodiles on the list of endangered species. Since then crocodiles have started to reappear on Lake Nasser, but not yet in the main Nile. The fishermen hate the crocodiles, who compete for their fish, get caught in and cut their nets, and sometimes attack and eat them, so they continue to kill the crocodiles when the government isn't looking. And there is still a lot of poaching and smuggling going on, even professional hunting safaris for well-heeled foreigners."

"If they are such deadly menaces why not just hunt them to extinction?"

Dr. El Din argues that crocodiles are an integral part of our natural heritage and ecosystem, a link in the chain of global diversity, and have as much right to share space on the planet as any other creature. They were in fact here millions of years before people and could claim first rights. They were in a fashion the first Egyptians. Through the rise and fall of empires, from the Pharaohs to the Ptolemies, through the epochs of the Greeks, Romans, Persians, Arabs, Ottomans, French and English, only the crocodiles stayed the same, until recently.

But I wonder how the fishermen can ever be convinced? The returning crocodiles affect their livelihood, their well-being.

"Ecotourism," is Dr. El Din's answer. He thinks a viable economic alternative to fishing would be making the wild crocodiles a tourist attraction, just as the gazetted paradises of sub-Saharan Africa have done with lions, Australia's Barrier Reef with sharks, and the Canadian outpost of Churchill with Polar Bears. "Crocodiles are a very valuable resource, and can be a significant tourist attraction. People want to see wild crocodiles in the sun."

Dr. El Din then describes how he has confiscated crocodiles from traders in the Aswan area and liberated them back to the Nile. He concludes by advising, "If in your travels you find a captured crocodile, set it free, if you can. Set an example. It could be a small gesture that saves a life, sends a message, and makes a difference. And the crocodile will then pray for you."

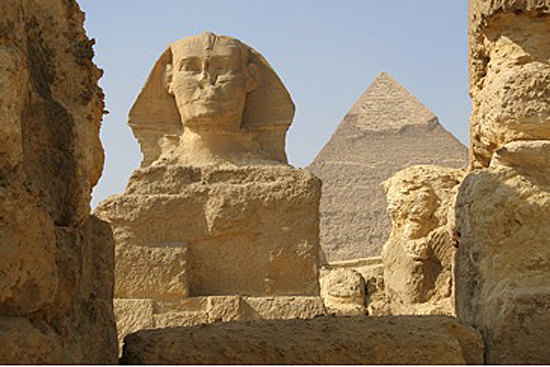

On the outskirts of Cairo is Giza, where I hire a camel and clop to see the great pyramids in the soft coral flush of dawn. Built some 4,500 years ago as way-stations to the afterlife, they are the lineaments of gratified desire. No matter how many images seen of the pyramids when in their presence the mind is slendered by awe. If there is an architecture of happiness, it is the pyramids, ancient elevators to a higher life.

I continue then south to Saqqara, through a land that looks like the scrapped hide of a camel, bits of hair still tufted to its tawny back. Saqqara is a vast, ancient burial ground featuring the world's oldest standing step pyramid.

While Memphis was the capital of Ancient Egypt, Saqqara served as its graveyard, and remained an important complex for burials and cult ceremonies for more than 3,000 years, well into Ptolemaic and Roman times. It is here I hook up with Dr. Zahi Hawass, head of the Egyptian Antiquity Commission, and a man temperamentally disinclined to keep any achievement quiet. Hawass wears brushed jeans, a pressed denim shirt, and his signature Indiana Jones hat, one he tells me is about to be licensed under his brand by a Chicago haberdashery. His famous enthusiasm bubbles when I ask him about Sobek.

"Sobek....that is so interesting. Nobody studies Sobek, but he was an important god. In fact, I just made two discoveries....Let me show you."

I follow Dr. Hawass's hat down into a dig in progress, where workers are sifting through a mud-brick tomb that dates back 4,200 years, to the start of the fifth Dynasty in the Old Kingdom. Grave robbers unearthed this tomb a few months previous, making it the newest major archeological discovery in Egypt.

Dr. Hawass uncorks his theory that three royal dentists are interred in these tombs, and points out hieroglyphs of an eye over a tooth, the symbol of the men who tended teeth.

Then he says that the tomb is marked with a curse, and points to a depiction of a crocodile with a beautifully curved tail, one of the oldest illustrations ever discovered of a crocodile: "The dentist put an inscription to say: 'Anyone who enters my tomb will be eaten by the teeth of Sobek."

"What about you?" I ask Hawass.

"Well, the thieves went to jail. As for me..." and he stretches a smile like a hammock, hanging out his belief in his own immunity.

Hawass then signals a couple of his workers, who carry down into the excavation site what looks like a large loaf of bread wrapped in a linen bandage...it is a crocodile mummy found in the house of an antiquity dealer near Giza recently. "The crocodile was the god of rebirth, and in the ancient Egyptian quest for immortality bringing Sobek with you secured a safe passage to the after world."

Hawass's dig is off in an isolated anhydrous patch but just off the road is the famous tomb of Mereruka, a popular tourist walk-through. I joined the throngs and filed through the labyrinthine chambers and catacombs, past storyboards of a hippopotamus hunt, fowling in the marshes, dwarfs making jewelry, scenes of fishing, gardening, and farming, an ancient catalogue of harmonic balance that reverses the telescope from today's hardships and irredentism.

There are enough plot elements in these halls to fill a periodic table. As I sweep my flashlight about I keep looking for the long-nosed image, and there at last it is, a fight scene in which a hippo is breaking the back of a crocodile, a not uncommon eschatological picture. Without death, of course, there can be no resurrection. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead the deceased pass through a series of gates guarded by crocodiles. The correct answer to a riddle opens the gate and leads the way to the everworld.

Read Part III here.